One-hundred-and-forty-six years ago this week, on May 20, 1875, much of the borough of Osceola Mills burned to the ground.

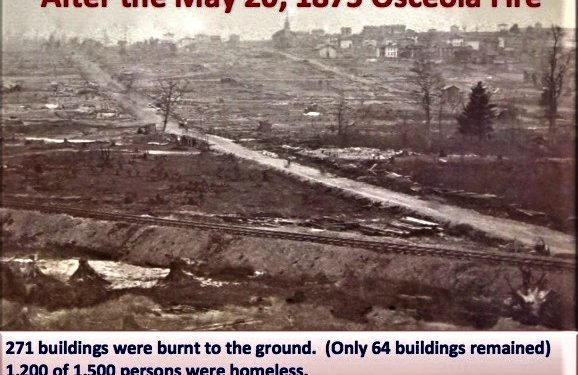

No one was certain how the fire started at the bottom of the town near Moshannon Creek, but within hours, 271 buildings were reduced to ashes and 1,200 of the estimated 1,500 town residents were homeless.

The brisk winds of May whipped the flames into a firestorm. Over the next two days, the fire line spread westward through the woods and brush that were remnants of logging operations to directly threaten Sterling, Brisbin, Parsonville and Houtzdale. Miraculously, no one was killed.

The damage to homes and businesses was immense. Newspaper reports listed names and detailed amounts of calculated losses. No report could gauge the bewilderment and shock felt by the ordinary working families who lost what little material possessions they had.

The spring of 1875 was a tense time in the coal regions of the Moshannon Valley. The fire happened against the backdrop of a bitter and occasionally violent and widespread coal miner’s strike that threw the Osceola Mills and Houtzdale area into chaos.

The misery of 19th century deep mining, with its horrific working and safety conditions, added to the low wages and heavy-handed company store system that kept miners in never-ending poverty and debt.

Desperation led them to strike for a 10-cent raise from 40 cents to 50 cents per ton of coal mined and loaded on to mine rail cars.

Coal operators refused the raise, arguing that they were being charged exorbitant freight and shipping rates by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the state-wide corporate powerhouse of the day.

Strikebreakers, mostly from Italy and Germany, were recruited at the wharfs in Philadelphia, kept in boxcars and then brought to Houtzdale to take over mining jobs.

None were fluent English speakers and likely had no clue of what mining entailed. They only knew that they were promised jobs.

No doubt they feared for their lives when they were met by jeering miners, some of whom felt sorry for the immigrants who were cruelly used. Others were eager to throw some punches.

Nevertheless, the strike, as most were then, was a failure and the local miners returned to work without their raise. They were also victims of the dreaded and later illegal private army of coal and iron police, who were little more than recruited thugs known for violent repression.

It was the striking miners who took for the woods between Osceola Mills and Houtzdale to light backfires, which stopped the flames. Osceola Mills was devastated but Houtzdale was saved. Striking miners, who had been reviled days before in some news outlets, were now the heroes of the day.

The news of the fire in Osceola Mills made national news. The New York Times, reported, on its front page, the details of the devastation on May 21, with the headline Destruction of a Town. The next day’s story began with Nothing is Left of the Town But its Site.

The photo was provided by Osceola Mills historian David Caslow. It looks as though only the northeastern section of town was spared. The photo resembles the images that showed the effects of World War II carpet bombing.