Free speech came to fisticuffs before alt-right white nationalist Richard Spencer could even begin his speech at Auburn University.

Students encircling the brawl said a Spencer supporter began jawing with an antifa, or anti-fascist, protester over Spencer’s right to speak. A punch was thrown. The men spun through the crowd, swinging fists and grasping for headlocks before thudding to the ground.

It was over in seconds with both men in cuffs — one of them bloodied — and carted off to jail.

Auburn had tried four days earlier to cancel Spencer’s speech Tuesday night. But a federal judge forced the public university to let him exercise his First Amendment rights.

The episode comes amid what critics say is a growing intolerance for the exchange of ideas at American colleges and universities. In recent months battles over free speech on campuses have descended into violence across the nation.

The University of California, Berkeley, erupted into near-riots in February during protests against professional provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos and again last week over President Donald Trump. When eugenicist Charles Murray spoke last month at Middlebury College in Vermont, protesters got so rowdy that a professor accompanying him was injured.

More and more American universities are avoiding controversial speech altogether by banning polarizing speakers. On Wednesday Berkeley said it would seek to cancel next week’s scheduled speech by right-wing pundit Ann Coulter, citing safety concerns.

And students say the middle ground on campuses is in danger of becoming quicksand, a place where neither side dares tread.

“There’s no test, just an escalation of hostilities on both sides,” said Tyler Zelinger, 21, a senior studying political science and business at Atlanta’s Emory University. “When there’s no more argument, there’s no more progress.”

Students are quick to shut down opposing ideas

Assaults on college free speech have been waged for decades, but they used to be top-down, originating with government or school administrators.

Today, experts say, students and faculty stifle speech themselves, especially if it involves conservative causes.

Harvey Klehr, who helped bring controversial speakers to Emory during his 40 years as a politics and history professor, said the issues college students rally around today come “embarrassingly from the left.”

Oppose affirmative action or same-sex marriage and you’re branded a bigot, he said. Where debate once elevated the best idea, student bodies are now presented slanted worldviews, denying them lessons in critical thinking, he said.

“History is full of very, very upsetting things. … Grow up. The world is a nasty place,” he said. “If you want to confront it, change it, you have to understand the arguments of nasty people.”

Berkeley political science professor Jack Citrin began attending UCB in 1964 during the advent of the free speech movement, when Berkeley students “viewed ourselves as a beacon of the ability to handle all points of view.”

Universities expose young people to ideas and challenge what they believe about science, politics, religion or whatever. But many students today exist only in the bubble of what they believe, he said.

“It’s an indicator of the erosion of the commitment to open exchange and a retreat into psychobabble,” Citrin said.

Trump’s rhetoric is spawning hate — on both sides

Twitter dubbed it #TheChalkening. Last year at Emory, someone used chalk to scrawl “Build the wall” and other pro-Trump messages near Emory’s Black Student Union and CentroLatino.

Some Emory students were livid and let the administration know it. One sophomore declared, according to the school newspaper, that protesters were “in pain.”

The reaction brought scorn from pundits such as HBO’s Bill Maher, who said he wanted “to dropkick these kids into a place where there is actual pain.”

As Emory sophomore Maya Valderrama, 20, left a February protest denouncing Trump’s policy on sanctuary campuses, she said the outcry over the chalkings was overblown. She wasn’t threatened by them, she said, but she understood the concern.

This wasn’t about politics, she said. Pro-Mitt Romney messages on campus hadn’t threatened anybody, but Trump is hostile to segments of the student body. The chalkings represented “a visual affirmation of his hatred,” Valderrama said.

Many students and their professors worry that when it comes to issues on campus, emotion rather than logic is driving the debate.

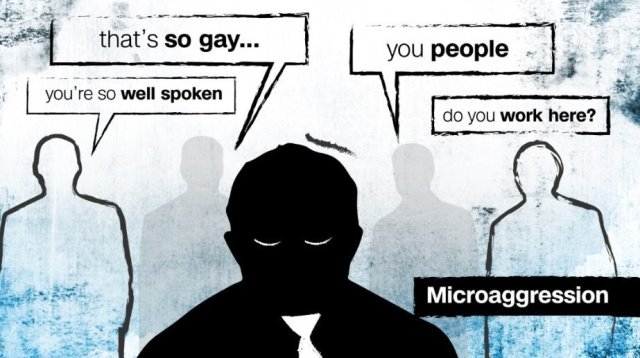

Some students complain that hypersensitive classmates railing about “microaggressions,” “trigger warnings” and “safe spaces” have committed assault on the First Amendment. Others, especially minorities, feel Trump’s rise to power has emboldened conservative students to spew vitriol.

Nathan Korne, a sophomore at Marshall University in West Virginia, welcomes Trump’s attacks on political correctness because he’s “tired of not being able to discuss open ideas.”

But Yasmine Ramachandra, a 19-year-old at Ohio’s Oberlin College, sees no silver lining. Trump is validating right-wingers who always wanted to snuff out certain speech, and his rhetoric has emboldened hatemongers, she said.

Two days after Trump’s election, she walked through a campus racial profiling protest where a group of counter-protesting bikers called her a terrorist and demanded she leave the country, Ramachandra said.

“The bigger repercussion is (Trump) validating these other people,” she said.

The anger cuts both ways, said University of New Mexico sophomore Alexus Horttor. She recently saw the Arab owner of a hookah shop kick a student out of his store over a Trump bumper sticker.

“People feel their way is the right way, and it’s only their way,” Horttor said.

Liberals are more likely than conservatives to suppress speech

Spencer. Murray. Yiannopoulos. All three have been attacked by students for having extreme far-right views.

Meanwhile, left-leaning speakers routinely appear on university campuses without fuss.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education maintains an incomprehensive database of more than 300 attempts to disinvite campus speakers since 2000. About three-quarters of the attempts involved pressure from liberals.

Evolution and Israel are among the most controversial topics. But more often the disinvitation attempt stems from disagreements over immigration, gender, race, religion, sexual orientation or abortion.

Yiannopoulos ticks several of those boxes.

The former Breitbart editor made free speech a buzzphrase when Berkeley protests turned violent during his appearance. The demonstrations made Yiannopoulos — now persona non grata after appearing to condone pederasty — a free speech martyr at the time.

UC Berkeley’s Citrin said that was the point. Yiannopoulos’ speech was staged to challenge the school’s commitment to free speech, he said.

“There were a variety of calls for it not to be permitted to occur by a group of faculty who, frankly, didn’t seem to understand the First Amendment very well,” the professor said. “Free speech at Berkeley took a hit when it was all said and done.”

While students that attended protests against Milo’s planned speech at Berkeley in February told CNN they were relieved he couldn’t share his message, others who watched from the fringes were disappointed — in a sense of principle.

“It’s a sad irony in the fact that the Free Speech Movement was founded here and tonight, someone’s free speech got shut down,” said Shivam Patel, a freshman who witnessed the protests on campus. “It might have been hateful speech, but it’s still his right to speak.”

Students believe bigots hide behind the First Amendment

When the chalkings appeared at Emory, some minority students felt targeted, said Lolade Oshin, 21, who is African American.

Later, after students complained about feeling hurt, a national columnist wrote their parents should’ve whipped their “spoiled asses with a cat o’nine tails.” National commentators chastised them as “snowflakes” — people too vulnerable to face opposing views.

Oshin, a senior business major, feels such criticism is unfair.

“As a black woman in America, I have no choice but to hear the other side,” she said. “But because those individuals are privileged, they don’t have to hear my side. … One side has grown up having to be sensitive and to navigate a white man’s world.”

Bigots hide behind free speech, she said, asking: How is it the Trump chalkings were free speech but student protests were not?

“Have whatever beliefs you want. Say whatever you want, but if I feel you’re dehumanizing me, I’m going to use the same right you’re using to fight your ideas,” she said.

Oshin also sees hypocrisy in the reaction to the Yiannopoulos pederasty controversy.

Conservatives defended Yiannopoulos after Berkeley, she said, but when he appeared to condone pedophilia rather than Islamophobia and bigotry, there were crickets from the right.

“Is it what is offensive or who is being offended that matters? It is very interesting how conservatives are not screaming freedom of speech now,” she said. “It seems to be a tactic used to quiet the marginalized and oppressed. But as soon as others feel threatened, it is not brought up.”

Some students are afraid to talk about touchy issues

University of Oregon law student Garrett Leatham, 29, believes hearing both sides is integral to understanding an issue.

“(Thomas) Jefferson did great things, but he owned slaves. We need to know both. Otherwise, we’re stuck believing Columbus sailed the ocean blue and helped the Indians,” he said.

Teens’ brains are developing, and critical thinking is essential to maturity, so “being able to listen to disagreeable opinions when you’re that young and understanding what they’re saying and why” is important to higher education, he said.

Horttor, the University of New Mexico sophomore, says her own growth has been stunted by the testy atmosphere on campus.

Take religion. Horttor’s mother is a Christian, but she knows many atheists.

The 19-year-old’s own leanings? “I don’t know what I believe in yet because I haven’t seen the man.”

But Horttor is reluctant to ask Christians why they believe and atheists why they don’t, because she doesn’t want to be ostracized.

But they will go to extremes to defend free speech

Liam Ginn, a freshman at the University of Southern Maine, faced his classmates’ fury this year when state Rep. Lawrence Lockman visited the Portland campus.

The lawmaker has lashed out at Islam and gays. In 2014, he apologized for saying that if abortion is legal, rape should be legal, too, because “the rapist’s pursuit of sexual freedom doesn’t (in most cases) result in anyone’s death.”

Students wanted Lockman disinvited, and as chair of the student senate, Ginn was part of a student government vote to remain neutral. He lost some friends over the decision, he said.

Ultimately, Lockman delivered his remarks on immigration — or “the alien invasion” — and students engaged him in heated debate, Ginn said.

Asked why he voted to remain neutral, Ginn, 24, said he’d never condone Lockman’s rhetoric. But he did a stint in the US Navy before beginning college, and the experienced changed his views.

“After putting five years down for this country, you realize you’re defending all the laws that we stand for,” Ginn said. “Otherwise, the past five years were a waste of my time.”

They will listen to speakers they disagree with if they’re civil

In 2015, liberal Sen. Bernie Sanders spoke at Liberty University, the Christian school in Virginia founded by evangelist Jerry Falwell.

Senior Hannah Scherlacher, 22, said most of her classmates don’t agree with Sanders’ views.

But when he visited campus there were no protests, no raised hackles, she said. Attendance at his speech was compulsory.

Sanders made points students disagreed with, but he knew his audience, she said. He told the crowd of 12,000, “I want to support my arguments with what you believe — your Bible, your Scripture,” Scherlacher recalled.

His “unifying tone” made Scherlacher “reflective on my role as a Christian to alleviate poverty.” She revisited her Bible to study Jesus’ condemnation of wealth and power.

And Sanders spurred debates that carried on after he left, the public relations major said.

“Everyone I talked to was glad he came,” she said. “It’s important to communicate with those we disagree with.”

But they will ignore speakers they see as hurtful

Bob Richards, founding director of the Pennsylvania Center for the First Amendment at Penn State, earned scorn himself when he brought porn publisher Larry Flynt to campus in 2001. Faculty and a Philadelphia radio station demanded a disinvitation.

Richards couldn’t understand why intellectuals didn’t jump at the chance to spar with Flynt. But he believes things may be worse now.

“We see more of a willingness on the part of the public to stop expression. They’re happy certain speech is cut out,” the journalism professor said. “If you put something like that on a ballot, people would vote to regulate expression.”

Ramachandra, the Oberlin student accosted by bikers, acknowledges clinging to her own truths. Oberlin is a bastion of the left, and it’s unlikely someone like Spencer or Yiannopoulos would be invited to speak at the Ohio school, she said.

If they were, there’d be anger but support. People would open up safe spaces to shield students from hurtful messages, she said. She’s fine with that.

A leader of Oberlin’s debate team, Ramachandra said the difference between Liberty’s reaction to Sanders and Berkeley’s response to Yiannopoulos is simple.

Sanders promotes policies, she said. Yiannopoulos was an alt-right darling who Twitter banned for harassment and who counts feminists, Muslims and social justice warriors as enemies.

If students want to protest Yiannopoulos, avoid him or shut him down, it has little to do with the free exchange of ideas, she said.

“I don’t think I’m missing out on any political discourse” by tuning him out, she said. “I’ve already come up with my own counterpoints so I don’t need them to come to campus and provoke me and hurt other people.”