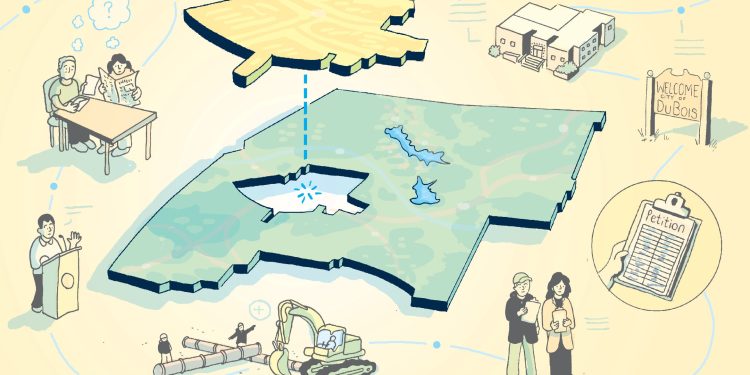

The ongoing consolidation between DuBois and Sandy Township is only the second one in Pennsylvania after lawmakers standardized the process. It has shown the limits of state law.

Min Xian of Spotlight PA State College

This story was produced by the State College regional bureau of Spotlight PA, an independent, nonpartisan newsroom dedicated to investigative and public-service journalism for Pennsylvania. Sign up for our north-central Pa. newsletter, Talk of the Town, at spotlightpa.org/newsletters/talkofthetown.

SANDY TOWNSHIP — In a little under two years, the place Cheryl Shenkle has called home for most of her adult life will cease to exist.

The rural community of almost 12,000 people in Clearfield County, an 80-minute drive northwest of State College, surrounds the City of DuBois. And on Jan. 5, 2026, the municipalities will consolidate into a new city, still called DuBois.

Shenkle feels uneasy about that future.

A lack of concrete plans from local officials fuels her anxiety, and she’s not alone, she said. Low- and fixed-income families in what she calls the more “country” part of Sandy Township are afraid that changes in taxes, utilities, or land use could put them in a bad financial position after the consolidation.

That’s not the goal of the union, of course. Municipal consolidations and mergers offer a way to increase government efficiency, reduce costs, and grow economies. For some communities, combining resources is necessary for survival. For others, it’s an opportunity to prosper.

A Spotlight PA analysis of mergers and consolidations in Pennsylvania since 1994 found that successful unions tend to have the backing of voters and government officials from the communities involved ahead of the final decision. These elements were lacking in the DuBois-Sandy Township consolidation process.

Plus, the creation of the new city — a rare occurrence in Pennsylvania — is also plagued by an extraordinary hurdle.

The City of DuBois has been embroiled in a sweeping public corruption scandal for more than a year. Allegations that the former city manager stole hundreds of thousands of dollars from public funds have shocked both communities’ residents and undermined voters’ faith in the consolidation.

The lack of guidance in state law on how to proceed amid the tumult and disagreement among Sandy and DuBois officials has exacerbated the worries of some township residents and laid bare flaws in the process.

Those gaps affect community planning and quality of life statewide. Mergers and consolidations are among the few ways that distressed local governments can solve fundamental operational problems. If the state legislature doesn’t address these shortcomings, other municipalities could be discouraged from considering such unions when they find themselves in trouble.

‘Marriage of consent’

Pennsylvania municipalities historically have pursued consolidations and mergers to improve their services and reduce waste.

That expectation mostly proves true, and decades ago lawmakers created a statewide process to help communities get what they hope for.

The Municipal Consolidation or Merger Act in 1994 established a uniform system for how local government boundaries could change. It did away with annexation, leaving the decision primarily up to voters.

“Now, it’s a marriage of consent, where before it was more a method of taking,” Gerald Cross, a senior research fellow at the Pennsylvania Economy League, told Spotlight PA.

In a merger, two or more municipalities combine and all but one of the original governments is eliminated, whereas a consolidation terminates all parties involved and creates a new entity.

Boundary changes can be initiated in two ways: Governing boards can pass joint agreements and present the question to voters, or voters can petition to put a referendum on the ballot.

Since the law was enacted in 1994, 17 mergers have been proposed in Pennsylvania, of which 11 received approval from voters. By comparison, only two out of 13 consolidation initiatives have passed during the same time.

All told, proposals for mergers are more than four times more likely to be approved than consolidations.

Nearly all approved mergers involved boroughs dissolving into neighboring townships, according to Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development data.

In at least six instances, the proposals were backed by both municipalities’ local governments leading up to the official vote, Spotlight PA found. Those municipalities detailed how they would come together in written agreements, many of which were built upon existing cooperations like sharing of police services.

Successful couplings also often involved a sense of urgency. South New Castle Borough in Lawrence County had no businesses and an eroding tax base before its merger with Shenango Township. Strausstown Borough in Berks County was struggling to pay for services that Upper Tulpehocken Township provided.

Potter County’s East Fork and Wharton Townships — populations 14 and 91, respectively, before merging — didn’t even have enough people to run their governments. Merging was the only way to sustain a functional municipality.

In some cases, the combination delivered better public services.

The City of Hermitage recently helped identify a manufacturer and a trucking company that would benefit from a land swap, Mark Longietti, director of business and community development for the city, told Spotlight PA. Longietti said the exchange gives one of the businesses the parking they need and allows the other to receive truck deliveries more efficiently.

This sort of proactive support for businesses wasn’t available in the former Wheatland borough, which merged with Hermitage officially on the first day of 2024, Longietti said.

While Pennsylvania municipalities fusing for survival has generally worked out, combining to improve status has had mixed results.

The 1994 consolidation of the former Borough of St. Marys and Benzinger Township in Elk County created the City of St. Marys, which is the second largest city by area in Pennsylvania. More than three decades later, City Manager Joe Fleming credited the consolidation with improving the quality of life in the city.

“I think it exceeded expectations,” Fleming said. “I don’t think the people that pushed forth the consolidation could ever imagine what the city has turned into and the capabilities and resources that we have now.”

But the creation of Northern Cambria Borough in Cambria County in 2000 — the only other consolidation proposal approved in the commonwealth since the Consolidation or Merger Act — serves as a cautionary tale.

Officials from the former Barnesboro and Spangler Boroughs hoped that combining the municipalities would attract more state and federal funding, the Tribune-Democrat reported in 2018. But the new borough missed out on qualifying for key grants because its population was too low.

Pete Barczak, a former Barnesboro Borough council member who helped plan the consolidation, didn’t think the communities improved because of it, the Tribune-Democrat reported.

Unresolved animosity among residents who lived through the transition left “a barrier there,” Wilbur Kelly Jr., Northern Cambria Borough council member at the time, told the newspaper. He called the consolidation “probably the worst thing we ever did.”

Hard feelings

Calvin Nixon’s grandfather was a Sandy Township supervisor nearly a century ago. Nixon remembers being told stories of bad blood between the township and neighboring DuBois. In one tale, DuBois providers refused the township’s request for electric infrastructure, forcing Sandy to get help establishing power lines from Clearfield, which is “over the mountain” of the Moshannon State Forest.

“And we’ve been mad at DuBois ever since,” Nixon said, half-jokingly.

Failed attempts at consolidating exemplify this history. Voters in DuBois and Sandy Township considered combining four times at the ballot box: 1989, 1995, 2002, and 2021.

Harry Yale rejected the proposal each time.

“All the promises they made? It’s not gonna happen,” Yale, who described himself as a lifelong resident of Sandy Township, told Spotlight PA.

Advocates for the consolidation pledged better roads, uniform water and sewage charges, and expansion of local business and industry. But the lack of information detailing those plans has made Yale pessimistic.

Shenkle worries that she and her husband could be compelled to ditch the well and septic system they own and connect to municipal water and sewage instead.

If the new city decides to run lines to their property — a call typically made solely by the municipality — the cost to connect would likely be too high for the couple.

“That would be the end of John and I in that house,” she said.

A March 2021 Pennsylvania Economy League study projected property tax rates would be lower for average homeowners in a post-consolidation DuBois. That projection was based on the assumption that the new city would save half a million dollars annually by cutting duplicate staff and not creating any new positions.

The DuBois-Sandy Township Consolidation Joint Board — consisting of elected officials from both governments — eliminated the positions of a manager, an engineer, and a police chief in April and began sharing personnel between the municipalities.

That should generate about $400,000 in savings from salary and benefits, Shawn Arbaugh, who became the new manager for both communities, told Spotlight PA.

Despite the reduction of those key staff, it is too early to determine whether the new city will adhere to the study’s projected lower property taxes, Arbaugh said, citing ongoing inflation.

“We will not know the answer to this until we develop a budget and then determine a tax rate to be able to support the budget,” he wrote in an email. He added that local officials still have more than three years to consider any zoning changes.

The study also said “improved long term regional financial health” would be a key benefit of the consolidation, because Sandy Township and DuBois showed signs of fiscal distress.

Both municipalities experienced budget deficits three out of five years between 2015 and 2019, the report said. The study predicted the trend would continue if the financial structures remained.

Sandy Township voters approved the consolidation in 2021 with a razor-thin margin of only 33 more votes than the opposed. The apprehension of people who voted no was intensified with the arrest of Herm Suplizio two years later.

Prosecutors charged the former DuBois city manager in March 2023 with stealing more than half a million dollars from public funds associated with an annual festival run by the city’s fire department and from the local United Way.

The money Suplizio handled in relation to the festival, called Community Days, was not monitored by the city, authorities said.

Suplizio, who has said he has “always been pro-consolidation,” told the Courier Express after the vote that “the City of DuBois and Sandy Township are tied too close to the hip not to be one — for the betterment of the entire area.”

The allegations of misappropriation by Suplizio cast doubts on his ardent support for consolidation and further soured some township residents’ attitudes toward combining finances with the city.

Citing “vast uncertainties and questions regarding the City’s finances,” the township sued DuBois in the Clearfield County Court of Common Pleas last year, petitioning to pause their ongoing consolidation until the criminal investigation of Suplizio and a forensic audit of DuBois’ finances were complete.

Shenkle led a campaign that got more than 1,200 township voters to support the request to halt the process. Her efforts were incorporated into the lawsuit.

But the state law governing how municipal consolidations work does not include a provision that lets courts modify the timeline once voters approve a consolidation. Even though DuBois ultimately decided not to contest Sandy Township’s petition, the countdown to when the new city must be created did not change.

Twists and turns

After the Pennsylvania Economy League report recommended consolidation in March 2021, Sandy Township polled residents. Officials said the results showed little promise of the proposal passing. So in June 2021, the Sandy Township Board of Supervisors voted four to one against continuing to pursue a consolidation with DuBois, ending talks that began more than a year prior.

But with less than five months remaining until that year’s municipal election, township Supervisor Sam Mollica, the lone yes vote, successfully campaigned to put the question directly before voters.

Cross, the researcher, considers voter-driven initiatives for municipal unions like this the state law’s weakest part.

When local elected officials approve a consolidation, they can draft an agreement to detail what will change. Cross compared a joint agreement to a prenup that helps voters understand exactly what the eventual marriage will entail.

But when voters circumvent elected officials to put the question on a ballot, “the problem there is the citizens can’t get together ahead of time and propose a joint agreement,” Cross said.

Former township Supervisor Kevin Salandra told Spotlight PA he voted against consolidation because of a crucial detail: He didn’t want the new city to keep the optional “council-manager” plan for its form of government.

DuBois is one of only two cities in Pennsylvania — the other being Altoona in Blair County, until it changed to a home-rule charter in 2015 — that chose this setup. Under this structure, an appointed manager becomes a chief administrator and oversees nearly all functions of the city. In DuBois’ case, this arrangement contributed to the outsized influence of Suplizio.

Salandra said he would have supported the consolidation if it set up a home-rule city, which would have given new DuBois more flexibility to govern itself — a status the economy league study also recommended.

Salandra also wanted new city leaders to be elected from wards, he said, rather than all at large, so that different areas could “keep a bit of their identity” — including the city, the township, and Treasure Lake, a private residential development in the north-central area of the township.

But the proposal voters approved opted for the council-manager form of government.

Now, elected leaders are undergoing the Herculean task of creating a new government despite reluctance among Sandy Township supervisors to do so.

Turning a corner

Tom Wagner, who helped oversee St. Marys’ consolidation in the early ’90s, thought for a long time that it made sense for DuBois and Sandy Township to consolidate and saw parallels in how the Clearfield County pair could benefit as his city did.

“Sitting in the woods in the middle of northwestern Pennsylvania, St. Marys was pretty much an afterthought,” Wagner told Spotlight PA. The consolidation made St. Marys “a larger dot on the map” in terms of attracting investments, he said.

The first attempt to consolidate St. Marys was a failed voter-driven initiative. The second time around, a joint commission was formed so that voters and leaders were on the same page.

It was “the faith that the community had and its leaders [had] that they would take this on … that this was all going to work” that made founding the City of St. Marys successful, he said.

The combined populations of the township and borough gave the new city enough residents to qualify for state grants. Wagner estimated hundreds of thousands of dollars have flowed into St. Marys each year thanks to that designation, funding services for people with disabilities and rehabilitation of housing units.

Despite the corruption scandal, Cross, the economic league researcher, said the rationale for the consolidation of DuBois and Sandy Township remains sound and is optimistic the area will eventually benefit from the move.

“What’s important there, I think, is to go forward with an attitude of, ‘Let’s fix what was wrong in the city that we have since learned … . Let’s make this the best government we can,’” he added.

Salandra lost his reelection bid in 2023. He said many of his actions were perceived as anti-consolidation.

“I tell people I live in DuBois,” Salandra said. The township has a DuBois address and ZIP code. To him the area is already interlinked.

Consolidation is “the best thing for the community,” he told Spotlight PA. “It just needs to be done properly.”

Jennifer Jackson, who took office as a council member for DuBois in January, shares that sentiment. Jackson said she understands why some township residents feel skeptical about consolidating with the city under its previous leadership, but emphasized that new leaders are now working toward common goals such as straightening out its finances.

And there’s a symbolic significance in having Arbaugh and DuBois’s engineer Chris Nasuti serve both the township and the city. DuBois Council Member Elliot Gelfand called the pooled leadership “an unprecedented period of cooperation leading up to formal consolidation” in an email to Spotlight PA.

Pennsylvania lawmakers could consider using legislation to prevent situations like the DuBois-Sandy Township consolidation and other mishaps, Cross told Spotlight PA. Requiring a joint agreement in a voter-driven referendum is among them.

State lawmakers on the Local Government Commission, a bicameral legislative agency, discussed potential fixes to the lack of clarity in Pennsylvania law months ago. One idea is for it to establish a mediation process for when disputes arise during transition. Another would give some flexibility to timelines of when mergers or consolidations must be completed.

Meanwhile, Jan. 5, 2026 slowly approaches.

At this point, Shenkle said she’s not entirely opposed to seeing the consolidation happen. Joining might make both sides finally leave the past behind, she said.

But she wants to see leaders work proactively to instill confidence in the process among residents and deliver on their promises.

Sandy Township and DuBois are “at a point of really turning a corner, a big time corner,” she said.

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify DuBois’ and Altoona’s forms of government.

SUPPORT THIS JOURNALISM and help us reinvigorate local news in north-central Pennsylvania at spotlightpa.org/donate/statecollege. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability and public-service journalism that gets results.