This month marks the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th U.S. constitutional amendment, which guaranteed women the right to vote in all local, state and national elections. It was a long time coming and the result of a 72-year struggle that began, in earnest, in 1848.

A woman’s past legal status was indeed inferior in most states. They lagged in education and business ownership. Women often forfeited property rights upon their marriage.

Desertion was more common than divorce and protection from abuse orders were virtually unknown. They were also thought, by many, even by some women, to be too emotional and not innately capable of taking part in political affairs and governance.

A “self-made man” was an honored term often used to describe men of success. A “self-made woman” was one rarely heard. Women were too often denied the opportunity for self determination.

As the Industrial Revolution spread from Britain to the United States, many young women found themselves working long hours, for low pay, and in often unsafe factory conditions.

Some educated women of means began to devote themselves to gaining enfranchisement and therefore the right to vote.

In 1872, Susan B. Anthony boldly walked into her Rochester, N.Y., voting precinct and cast a vote. She was later arrested and tried for “illegal voting.”

Found guilty, she and many others, who often took part in the movement to abolish slavery, began to organize, state by state, to realizing their dream of equal suffrage.

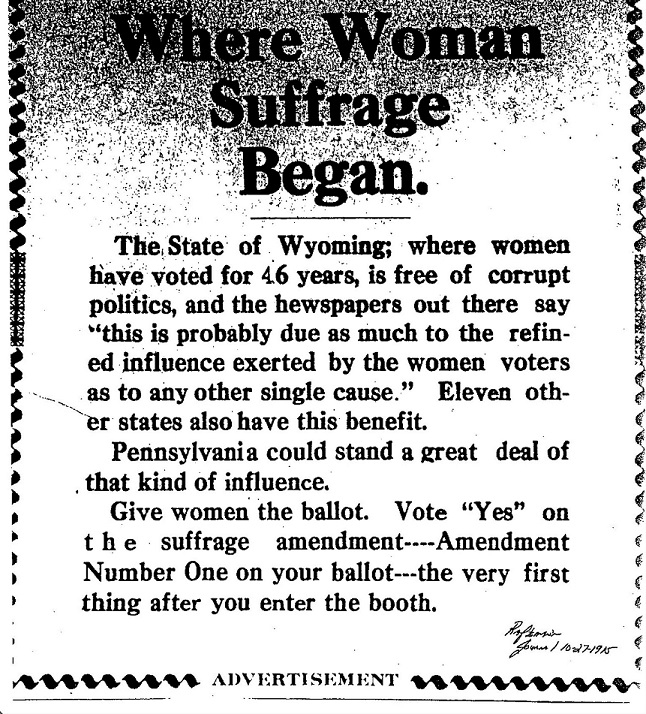

As early as 1876, the territory of Wyoming, where women often led harsh frontier lives, entered the Union as the first and only state where women voted.

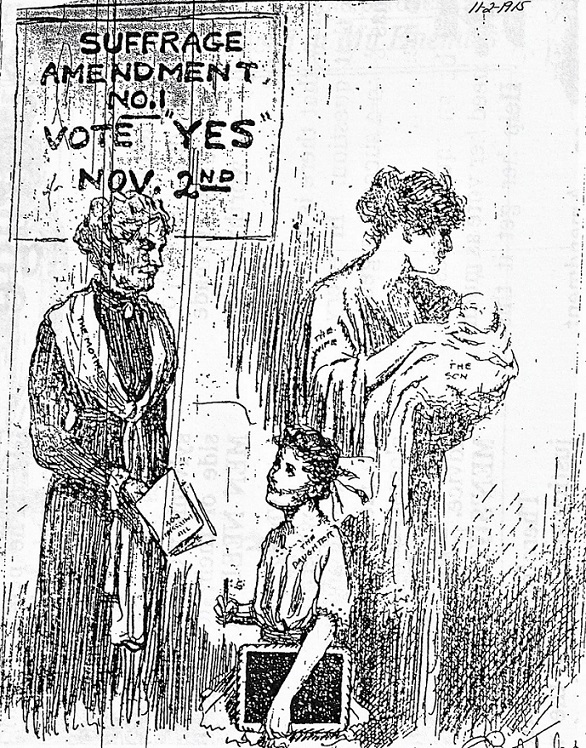

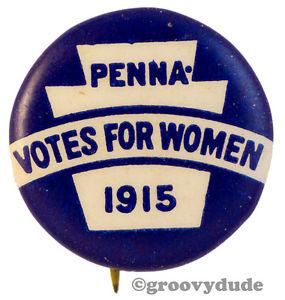

The process of convincing legislators, in state after state, was painstaking slow and often unsuccessful. In 1915, after many suffrage marches and lobbying, the Pennsylvania General Assembly placed a women’s voting referendum on the November ballot. Male voters, over the age of 21, would decide the issue.

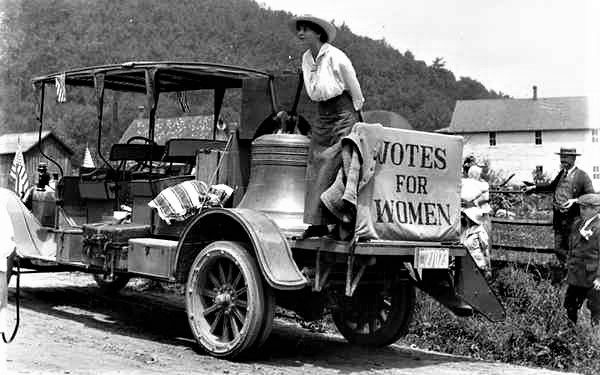

Suffrage groups swung into action. Katherine Wentworth Ruschenberger, of Chester County, financed a modified flat board truck, which held a one-ton replica of the Liberty Bell, to tour the most remote parts of Pennsylvania and bring the suffrage message to rural and small-town voters.

The bell was known as the “Justice Bell.” It had its clapper bolted to the inside to prevent it from ringing until Pennsylvania women had the right to vote.

All newspapers in Clearfield, DuBois and Philipsburg, except the Raftsman’s Journal, endorsed women’s suffrage.

They reflected the sentiments of the voters who three years prior, carried the area for Theodore Roosevelt’s new Progressive Party, which endorsed the movement.

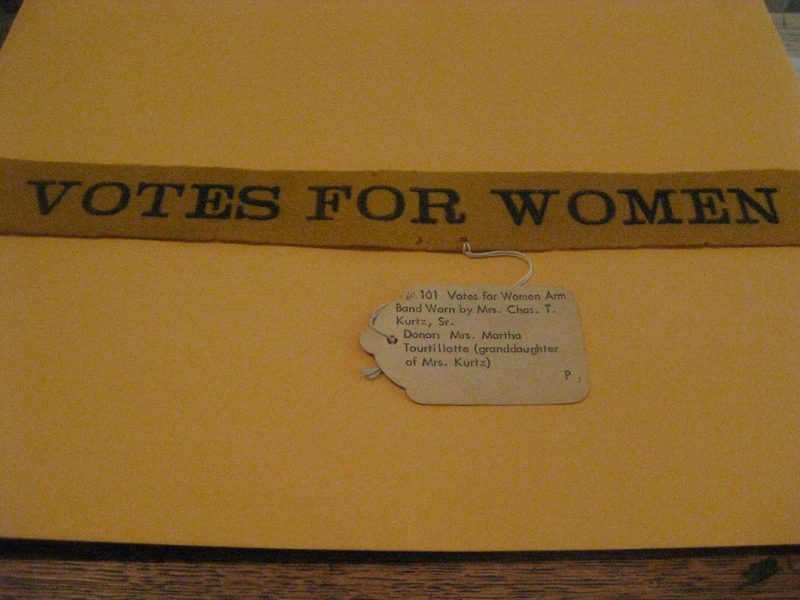

In Clearfield, Mrs. Robert Somerville, Mrs. Fred Betts and Mrs. Charles Kurtz were prime organizers of the ground campaign to welcome the suffrage bell truck as it traveled over the area’s dirt roads.

August of 1915 would see road show of passion unlike any seen in Clearfield County.

Editor’s Note: This is Part One in a three-part series on the Women’s Suffrage Campaign in Clearfield County.