A new gene therapy drug, the first in its class, was recommended for approval to the US Food and Drug Administration by an advisory committee on Wednesday. If approved by the FDA, the agency would consider it the first gene therapy to hit the market.

The drug may provide a second chance to some leukemia patients whose first-line drugs have failed.

A panel of experts voted to endorse the immunotherapy drug, known as tisagenlecleucel, which treats a type of leukemia that is more common among children. Ten committee members voted in favor, and one left early without voting. None voted against.

The drug enables patients’ own immune cells to recognize and kill the source of the cancer: a different immune cell gone awry.

“Which one wins is really the question of life or death,” said Dr. Catherine Diefenbach, clinical director of lymphoma at the NYU Perlmutter Cancer Center. Diefenbach, who was not involved in researching the drug and has no ties to its manufacturer, Novartis, described its results as “astounding.”

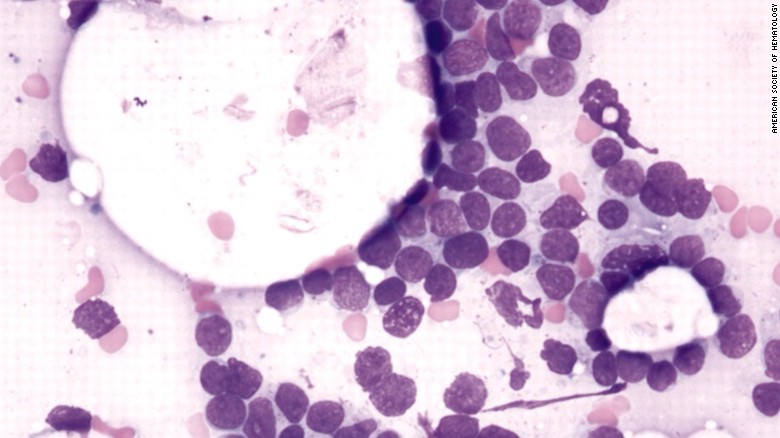

The research presented to the committee studied the drug as a treatment for the relapse of a blood cancer known as B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or ALL. This is the most common type of cancer among children, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Nearly 5,000 people were diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 2014, the most recent year on record, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Although more than half of those with this diagnosis were children and teens, they represented only 14% of those who died that year.

The vast majority of people with ALL recover through other treatments, including chemo, radiation and stem-cell transplantation. But if the cancer comes back, the prognosis can be dire.

“The patients who are left behind when chemotherapy doesn’t work are left in really tough shape,” Dr. Stephan Grupp, director of the Cancer Immunotherapy Program at Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania, said Wednesday at the FDA advisory committee’s meeting. His hospital is one of 26 clinical centers that participated in the study, and he served as the lead investigator there. As such, he has studied and treated patients with tisagenlecleucel for over five years and receives research support from Novartis.

But the drug has side effects that can be fatal, such as cytokine release syndrome or CRS, which “looks like sepsis” and causes blood pressure to drop dangerously low, said Diefenbach. This could limit the drug’s availability to those hospitals that are specially equipped to deal with this complication, she added.

In this pivotal study informing the committee’s decision, roughly half of 68 patients receiving the drug experienced high-grade CRS, though none died from it.

Slightly fewer patients experienced neurological side effects, such as seizures and hallucinations, according to the committee’s briefing document.

And because the treatment kills one type of immune cell, patients are more likely to come down with certain infections. At least three patients died with various infections — including viral, bacterial and fungal — more than a month after the drug’s one-time infusion, according to the brief.

But the overall effectiveness of the drug and the lack of other options seem to have won the committee over: Based on the available data, patients had an 89% chance of surviving at least six months and a 79% chance of surviving one year or more, with the majority being relapse-free at that point.

“They’re taking some people that had uncurable diseases and potentially turning them into curable diseases,” said Dr. Joshua Brody, director of the Lymphoma Immunotherapy Program at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine. Brody has helped design trials for similar drugs but not for Novartis.

Tisagenlecleucel is a type of immunotherapy called chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, or CAR-T.

CAR-T drugs like tisagenlecleucel are made by removing immune cells from a patient, genetically modifying them using a virus and putting them back into the patient. The virus creates a new cell receptor — which is, in Novartis’ case, part mouse — that targets another receptor on the cancer cells: CD19. This modification of the cells causes them to attack the cancer cells.

By modifying immune cell DNA, this method could, in theory, lead to other cancers — a longtime concern for gene therapy. But researchers have found no cases of this happening with the CAR-T treatment so far. Brody said it could take decades to conclusively say this does not happen.

“We’ve never seen this theoretical thing,” Brody said, arguing that the chance of any adverse event happening is certainly smaller than the certain death of relapsed cancer. “It’s not an opinion. This is straightforward numbers.”

Brody said personalized immunotherapy treatments like this one require that patients use their own immune cells because they would “almost never (find) a match” in an off-the-shelf product.

“You can put someone else’s red blood cells into you,” he said. “You can almost never put someone’s (immune) cells into you.”

“This therapy will no doubt save the lives of many children and young adults who have had no other effective therapy,” said Dr. John Maris, a pediatric oncologist at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and leader of the SU2C-St. Baldrick’s Pediatric Cancer Dream Team. “This is truly a turning point in the management of this disease.”

Kite Pharmaceuticals has another CAR-T drug up for FDA priority review for the treatment of lymphoma.

The Novartis drug would not be the only FDA-approved drug to target CD19; Amgen’s blinatumomab treats ALL using this target, but “it’s overall not quite as good” as the data coming out of the Novartis trials, Brody said.

The FDA previously approved Amgen’s T-VEC, which injects a modified herpesvirus into melanoma cells, causing them to rupture. The same goes for personalized immunotherapy: Dendreon’s Provenge was FDA-approved to treat prostate cancer in 2010, for example.

Novartis refers to the drug as immunotherapy, not gene therapy. The FDA, however, would classify it as gene therapy.

The FDA does not have to follow the recommendation of their advisory committees, although it often does. The agency declined to comment on when it would issue a final decision on the committee’s recommendation. Novartis expects the FDA to make a final decision by October but declined to comment on the drug’s potential price tag.