On April 12, in an interview with Fox Business Channel’s Maria Bartiromo, President Trump made clear that North Korea’s ongoing testing of missiles would not go without a response from the US.

“We are sending an armada. Very powerful,” Trump told Bartiromo. “We have submarines. Very powerful. Far more powerful than the aircraft carrier. That, I can tell you.”

Read those words carefully: “We are sending an armada.”

Fast-forward to a report Tuesday in the New York Times headlined: “Aircraft Carrier Wasn’t Sailing to Deter North Korea, as U.S. Suggested.” What the Times reported is that the Carl Vinson and three other ships in its group were, at the moment Trump and his administration were touting them, headed “to take part in joint exercises with the Australian Navy in the Indian Ocean, 3,500 miles southwest of the Korean Peninsula.”

The communications mix-up, according to the Times, was the result of “a glitch-ridden sequence of events, from an ill-timed announcement of the deployment by the military’s Pacific Command to a partially erroneous explanation by the defense secretary, Jim Mattis.”

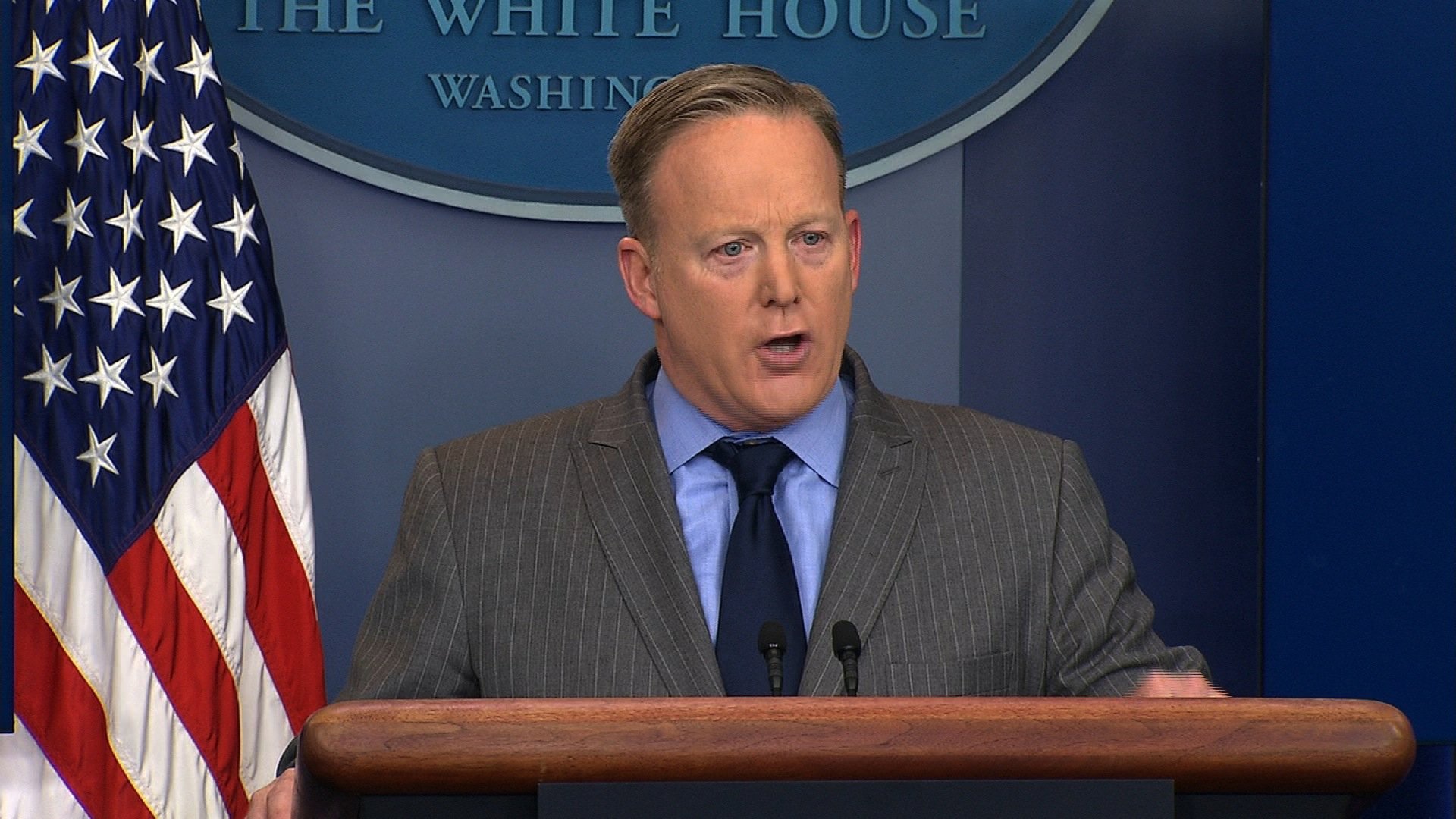

Except not at all, if you take White House press secretary Sean Spicer’s word for it. “We have an armada going toward the peninsula. That’s a fact,” Spicer told a skeptical press corps during his daily briefing on Wednesday.

Spicer’s argument goes like this: Trump said there was an armada headed toward the Korean peninsula. There is. So, in the broadest sense of the word “sending,” Trump was 100 percent right.

But, go back and read Trump’s quote above — for the third time, and yes, I am counting. The clear implication that Trump is making is that the “armada” is chugging to the Korean peninsula literally as he is speaking to Bartiromo. And that it is the sort of muscular response that the world community can and should expect in the aftermath of future provocations.

That message wouldn’t be sent as powerfully if Trump has told Bartiromo: “We are sending the Carl Vinson to the Korean Peninsula after it gets back from some maneuvers in the Indian Ocean.” The sense of urgency, of an immediate — and tough — reaction to the threats of a rogue nation would be lost.

Remember that President Trump is a big believer in political theater and the power of perception. And that moment with Bartiromo was just too good to pass up. A muscular leader sending a message to a country he believes was badly mishandled by his predecessor.

And so, Trump said what he said — which, as Spicer rightly points out, wasn’t a lie. It just wasn’t the whole truth.

Trump has stretched the expectations of what a president can do or say almost since the day he entered the presidential campaign in June 2015. This is just the latest example.