Richard Cole was not thinking much about the future when flying in the surprise Doolittle revenge raid on Japan 75 years ago Tuesday. He says he was scared all the time. Now, at age 101, he is the last survivor of the 80 gallant men who successfully bombed Japan and delivered a giant morale boost for the United States just months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Doolittle Raiders were beloved by a nation caught up in World War II. Cole will mark the 75th anniversary in ceremonies held at the National Museum of the US Air Force at Wright Patterson Air Force Base In Dayton, Ohio.

Lt. Col. Cole said, “It’s kind of lonely because I’m the last one.” When pressed about what the 75th anniversary of the attack means to him, Cole, with a twinkle in his eye, said, “It means I’m getting to be an old man.” Later, Cole said on the anniversary, “You think about the whole group.”

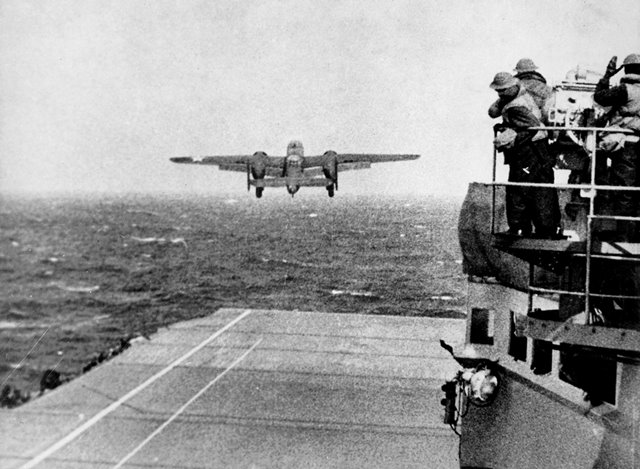

The 80 pilots, navigators, engineers, bombardiers and gunners took off in B-25 Mitchell bombers from the USS Hornet in the Pacific Ocean bound for Japan. A bomber takeoff from the deck of an aircraft carrier had never been done. The crew found themselves scrambling to make a hasty takeoff, 12 hours ahead of schedule, after they were spotted by Japanese fishing boats. The early departure also meant the planes would likely run out of gas before landing in friendly China. Cole was the co-pilot in the lead plane alongside the commander of the mission, Jimmy Doolittle.

Cole grew up in Dayton, admiring Doolittle, who set and broke many aeronautical records. Now here he was hurtling down the narrow deck of the Hornet in a small cockpit with Doolittle. His job? Making sure Doolittle was happy, he said, and handling the flaps on the plane so the engines wouldn’t overheat. Cole said people thought the takeoff would be the most dangerous part of the mission. “It turned out to be one of the easiest things,” he said. Cole later added, “Besides, I was flying with the best pilot, so why worry?”

The B-25 takeoff was filmed by US military cameramen on the Hornet and on nearby ships. Their fellow Doolittle Raiders waited anxiously in the 15 B-25 bombers behind them. Hundreds of the Hornet’s crew watched from the deck and the bridge in suspense. The order had been given. If a plane stalled or a technical problem developed approaching takeoff, it would be pushed into the sea in order to get the other planes in the air on time.

Cole described Doolittle as being very patient and not a ‘blustery type of individual.” The men were teamed after Cole’s scheduled pilot was replaced and an operations director said, “I’ll crew you up with the old man (Doolittle), if you do OK.” Cole and the other raiders had trained in Florida with no clue as to their destination or mission. It was all top secret. Crews were told the assignment would be dangerous and they could pull out if they wanted. None did.

The raiders flew at very low altitudes to avoid detection, 200 feet above the water. The planes arrived over Tokyo 12 hours ahead of schedule, making it a daylight raid instead of the planned night raid. A coincidental air raid drill conducted in Tokyo that morning did not prepare military defenses for the Doolittle Raiders. Bombs were dropped on their targets, oil storage facilities and military installations.

Some pilots reported seeing Japanese military planes in their vicinity, but the planes moved on, apparently thinking they were Japanese aircraft. It was the first retaliation against Japan in response to Pearl Harbor. Cole said, “I felt pretty good that we had done what we were supposed to do.” Then the race was on, as gas ran low, to land in mainland China and seek help from Chinese supporters who were living under Japanese rule.

They didn’t make it.

Doolittle ordered his crew to abandon the plane. Cole and almost all the Raiders had no experience jumping out of aircraft. In darkness and stormy weather, Cole leaped with his parachute and learned one thing quickly. “They don’t give a Purple Heart for self inflicted injuries. I gave myself a black eye” in pulling the ripcord so hard, he said.

He eventually landed in a pine tree and stayed their overnight. Chinese nationalists found him and brought him to a building where he was surprised to encounter Doolittle. The mission’s commander went to the crash site and sat morosely on the wreckage, telling one of the crew that he felt the entire mission was a failure and he would be court-martialed.

Doolittle feared the worst for the 16 planes. Engineer Paul Leonard consoled him, telling Doolittle he was wrong. He promised Doolittle the mission would be viewed as a success and the crews would be hailed as heroes. Back home, the raid was stunning news, with screaming headlines about the raid on the front page of daily newspapers. Japan was shocked. Cole said, “It told the people of Japan their island could be struck by air.”

Everything didn’t go completely smoothly. Eleven crews had to bail out of their planes. Four bombers crash-landed. Pilot Ted Lawson lost a leg. He would go on to write the best-selling book “Thirty Seconds over Tokyo,” later a hit 1944 film. One crew flew to the Soviet Union and was interned before eventually being set free. Eight men were captured. One starved to death in a Japanese prison camp and three were executed by the Japanese.

Cole and others went right back into the war after the Doolittle Raid. Cole flew transport planes carrying cargo and glider-borne troops in India, China and Burma. Some of the Raiders were killed fighting in the European theater.

After the war ended, the crews returned to civilian life. Doolittle lived up to a preraid promise of a party if the attack succeeded. The tradition would go on. A special feature of every reunion was the crew sharing a cognac in silver goblets with each Raider’s name engraved right-side up and upside-down. If a Raider passed away during that year, the goblet would be turned over.

A toast was made each year until finally there were only four Raiders left alive in 2013. Cole gave the final toast after the remaining four Raiders agreed that their age and inability to travel would make it the last reunion. Cole raised his glass before a large audience at the Wright Patterson Air Force Base and said, “I propose a toast to those who were lost on the mission and to those who have passed away since,” adding, “May they rest in peace.”

In June, 2016, David Thatcher, tail gunner, died at age 96, leaving Cole as the last surviving Doolittle Raider.

I interviewed Cole at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredricksburg, Texas, not that far from his home. A B-25 from the era sat behind us. Tourists strolling the museum entered an exhibit on the raid. Another surprise from the Raiders: The visitors had no idea one of the pilots from the actual raid was sitting in front of them.

I asked Cole his secret to living past 101. He simply said, “Keep moving.” He said he would like to be remembered along “with the rest of the people that had an impact on winning the war.” I asked Cole if he felt he was a hero. A quick response. “No.”

You make the call on this, the 75th anniversary of one of America’s greatest military accomplishments.