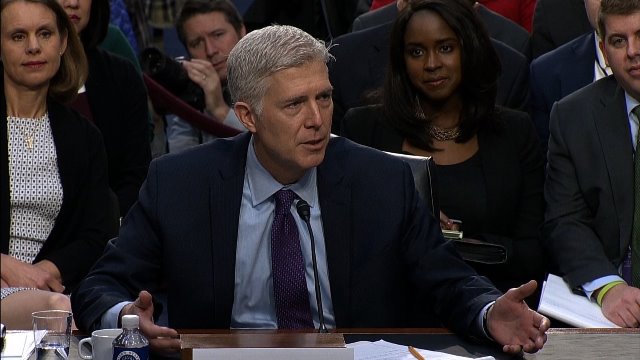

Neil Gorsuch has made it all the way to the hallowed hallways of the Supreme Court.

Gorsuch took his official oath to become the ninth justice in a short ceremony Monday morning, before a public ceremony later at the White House.

Now, after a lifetime of preparation and several grueling weeks as a nominee, he starts his tenure as the junior-most justice. The new guy. The rookie.

Sure, his vote on a dream docket of constitutional and statutory cases will be equal to any other justice. They all wear the same black robes, after all.

But someone has to open the doors and lead the cafeteria committee.

With no time to catch his breath after meeting with more than 80 senators, enduring 20-plus hours of testimony and watching the Senate go nuclear over his nomination, he’ll have to learn quickly. And even though he served as a clerk at the highest court in the early 1990s, he’ll still have to adjust to the peculiar place that is the Supreme Court. It’s steeped in tradition and seniority weighs heavily.

The junior-most justice starts off at the bottom of the heap, sits on a far wing of the bench and speaks last at conference.

Indeed, the conference — the regular closed-door meeting where the justices discuss cases — has an unusual tradition.

Only justices are allowed to attend. No clerks, no assistants, just the nine.

And the junior-most justice is assigned the task of answering the door. Seriously.

It’s a job that Justice Elena Kagan, confirmed to the bench in 2010, is likely relieved to relinquish.

She lightheartedly described the job qualifications at a Princeton appearance in 2014.

“The junior justice has to answer the door,” she began.

“I mean literally, if there is a knock on the door, and I don’t hear it — there will not be a single other person who will move, they will just all stare at me until I figure out ‘oh, I guess somebody knocked on the door.'”

Why might people knock on the door? “It’s like ‘knock knock, Justice X forgot his glasses’ … ‘knock knock, Justice Y forgot her coffee.'”

“So there I am popping up and down. I think that is a form of hazing, don’t you?” she said to laughter.

What’s for lunch?

Besides conference duties, the junior justice is also traditionally assigned to the cafeteria committee.

The court is a close-knit place, and staff and a number of the justices divide up into committees dedicated to the functioning of the institution.

One lofty assignment — often doled out to senior justices — is the budget committee.

The cafeteria committee is a decidedly less lofty assignment.

Justice Stephen Breyer served there for a near record-breaking 11 years during a stretch when the court’s membership didn’t change.

Gorsuch will have popular shoes to fill. Kagan gained the instant respect of colleagues, clerks and beat journalists when she spearheaded the installation of a frozen yogurt machine.

Help from your new friends

The new job comes with no handbook, no orientation sessions. Other justices in their early days have leaned on their colleagues.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor relied upon Justice John Paul Stevens to serve as a mentor in her first several weeks. In 2016, she called him her “barometer” in part because he assured her that it was okay to be a solo voice at times.

“He gave me the courage to understand that some things just have to be thought about,” she said during an appearance at the University of Wisconsin Law School.

Justice Clarence Thomas credited the late Justice Antonin Scalia with helping him learn the ropes. “I can honestly say that as beat up as I was when I got there with the workload, I don’t know how I would have gotten through if he hadn’t been there,” he told an audience hosted by the Federalist Society in 2013.

In 2015, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg recalled being dismayed about her first opinion assignment in 1993 because it dealt with an impossibly complicated congressional law. She thought her first opinion might be more of a softball. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor came to her rescue with her usual straightforward advice.

“Just do it,” the first female justice on the bench told the second. When the opinion was released in court, O’Connor slipped her a note, Ginsburg recalled. “This is your first opinion of the court, it is a fine one and I look forward to many more,” the note read.

Meet the clerks

And then there’s the issue of clerks.

Interviews with several former clerks who served for first-time justices reveal that those first few weeks can be daunting.

“Justices are appointed so rarely that they are left to figure out things out on their own,” said Deborah Merritt, who served as a clerk to O’Connor during her first term.

Merritt remembers an unusual situation. She said that O’Connor contacted her first four clerks shortly after her nomination. They were then hired by the chief justice on the court’s general payroll to begin preparing memos and materials for the new justice.

“When the Senate Judiciary Committee voted to confirm Justice O’Connor, Court officials drove us across town so that we could meet her and deliver the memos we had prepared,” Merritt said.

After her first conference on argued cases, Merritt said that O’Connor was dazzled. “She described to us how momentous it felt to sit in that historic conference room with just the other eight justices,” she said.

Alexander “Sasha” Volokh served as a clerk for incoming Justice Samuel Alito. Volokh had been on the court clerking for O’Connor and says he was relieved when Alito asked him to stay on. Alito, a former appellate court judge, knew his way around a legal opinion and oral argument. But different kinds of cases come to the Supreme Court, including the sober responsibility of deciding last-minute death penalty appeals.

Volokh explained that each chamber had a clerk that stayed up late to handle any last-minute stay applications.

“My first question,” Volokh said in an interview, “was ‘if we need to wake you up, do we have your standing permission to do so?’ Alito said ‘yes.'”

When Gorsuch arrives, the eight justices might have a few cases lined up that are split 4-4.

Peter Keisler clerked for Justice Anthony Kennedy, who faced a similar situation during his first term.

“Justice Kennedy arrived at the court in February 1988, during the middle of the term. There were a couple of cases that had already been argued but on which the court was deadlocked 4-4. So the court issued an order directing that those cases be reargued,” Keisler remembered.

He said that while advocates always try to answer questions as persuasively as possible, he sensed that attorneys gave “special solicitude” to Kennedy during the rearguments, knowing his would be the decisive vote.

“Perhaps, in that sense,” he said, “those cases were a harbinger of things to come.”