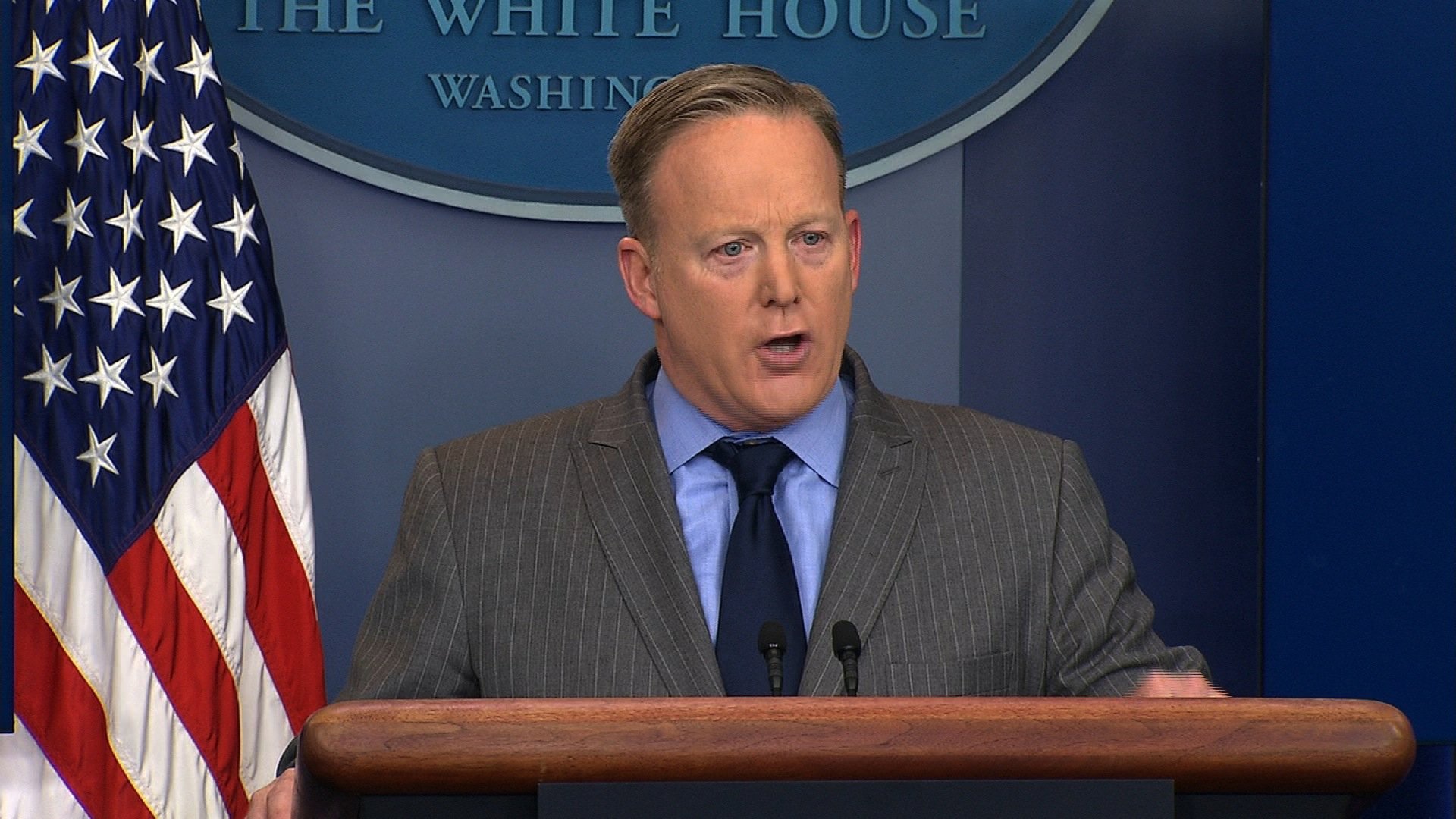

White House press secretary Sean Spicer said twice Monday that the Trump administration will respond if the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad uses barrel bombs against his own people, something that’s been a regular occurrence in the six-year civil war.

“If you gas a baby, if you put a barrel bombing to innocent people, I think you can see a response from this president,” Spicer said in response to a question during his daily briefing. “That’s unacceptable.”

Spicer said the use of the crude, unguided explosives, would cross a line for Trump, who last week authorized cruise missile strikes on a Syrian base after the regime used chemical weapons on its own people.

But shortly after Spicer’s press briefing, multiple White House officials looked to clarify the comments, implying the press secretary misspoke.

Spicer “did not signal a change in administration policy,” an official said, adding that it was Spicer’s attempt to signal Trump is “never going to rule anything out” when it comes to responding in Syria.

The attempted explanation was aimed at avoiding drawing a line in Syria that the Trump administration will have to follow, something the Obama administration dealt with after then-President Barack Obama drew a “red line” that Trump and other Republicans routinely exploited.

The change would mark a significant shift in US policy toward Assad, whose regime is accused of near daily use of the bombs, which are banned by international law because of their propensity to aimlessly maim and kill.

The bombs, which can be dropped from helicopter and don’t need fixed wing aircraft, are difficult to police. In order to stop their use, the United States would have to take out the fabrication factories and storage sites used to make the barrel bombs.

“The sight of people being gassed and blown away by barrel bombs ensures … we hold open the possibility of future action,” Spicer said without prompting earlier in the briefing.

The bombs, which typically consist of barrels stuffed with explosives and objects, such as nails or shrapnel, are used to maximize the amount of damage and death without the cost of most sophisticated weapons.

In 2014, the opposition group Local Coordination Committees of Syria told CNN that at least 25 children were killed when barrel bombs hit an elementary school.

White House aides have made clear that Trump, before the strikes earlier this month, was moved by pictures and video of the aftermath of the chemical attack in rebel held areas.

But Spicer also emphasized despite name-checking barrel bombs and gassing children, the White House does not want to advertise its moves.

“The President’s made clear throughout his time in the campaign, through the transition and now as president, that he’s not going to telegraph a response to every corresponding action because that just tells the opposition or the enemy what you’re going to do,” he said.

Spicer also defended Monday the use of force in Syria, arguing Trump did not need congressional approval because the strike was in the United States’ national interest.

“Article II of the Constitution is pretty clear,” Trump said, referring to the part of the Constitution that gives the President “executive power” to give some room to use force without congressional approval.

“When it’s in the national interest, the President has the full authority to act,” Spicer said. “He did that.”

Article I of the Constitution, though, gives Congress the power to “declare war” and support armies, not the President.