They’re spared the glances. The “go back to your country” slurs facing so many undocumented migrants in the US. But they live in fear. They don’t call the police when there’s a break in. They think twice before they bring a sick child to the emergency room. Only, they’re white – and they’re Irish.

An estimated 50,000 undocumented Irish immigrants live in the United States — they make up a small percentage of the more than 11 million undocumented immigrants living there, the majority of whom were born in Mexico.

“It is easier being illegal here when you’re white,” Shauna, an undocumented Irish immigrant, tells CNN. “It’s not easy, of course, you have that paranoia but there isn’t the racial element. It’s a bit easier to stay under the radar.”

But there’s a growing sense of fear in the community since the election of President Donald Trump.

“I’ve never seen fear like this here,” Oliver Charles says standing in front of his butcher shop on McClean Avenue, in the predominantly Irish neighborhood of Woodlawn in the Bronx, New York.

“The fear is always there but now everybody is talking about it and everybody is worried.”

A sign in Charles’ store window reminds passersby to put in their corned beef order ahead of St. Patrick’s Day — a dish traditionally enjoyed on Ireland’s national holiday on March 17.

Charles, who came to the US more than 40 years ago and is now a US citizen, doesn’t ask his customers’ immigration status, but he suspects that many are undocumented.

“That could affect my business,” he says of Trump’s proposal to deport America’s undocumented immigrants.

Fear

Across the street is the Aisling Irish Community Center. Its windows full of job and apartment listings, it’s an organization helping immigrants with legal advice and mental health services.

“I haven’t seen this level of anxiety or fear,” the center’s director Orla Kelleher told CNN.

“People are generally anxious when they’re out and about and are electing to lay low now because it seems that the ICE agents are using their discretion in a much greater capacity now than ever before.”

She says there has been a three-fold increase in the number of undocumented Irish people seeking counseling services since President Trump’s January travel ban.

Out West

With its street full of Irish bars and stores selling Irish products like Tayto potato chips and black pudding — a type of sausage made using pork blood — Woodlawn has one of the highest concentrations of Irish immigrants in the US, but the undocumented Irish are spread far and wide.

Three thousand miles away in San Francisco, Shauna is also anxious. She came here in her early twenties.

“This is where I became an adult, my life is here,” she says.

Like many undocumented Irish, she entered the US legally on a holiday visa, thinking she’d stay a few months, a year at most. After long overstaying her holiday visa, she’s still here ten years later.

It is estimated that a third to a half of all undocumented immigrants in the US have overstayed visas, rather than coming into the country illegally.

Why they come

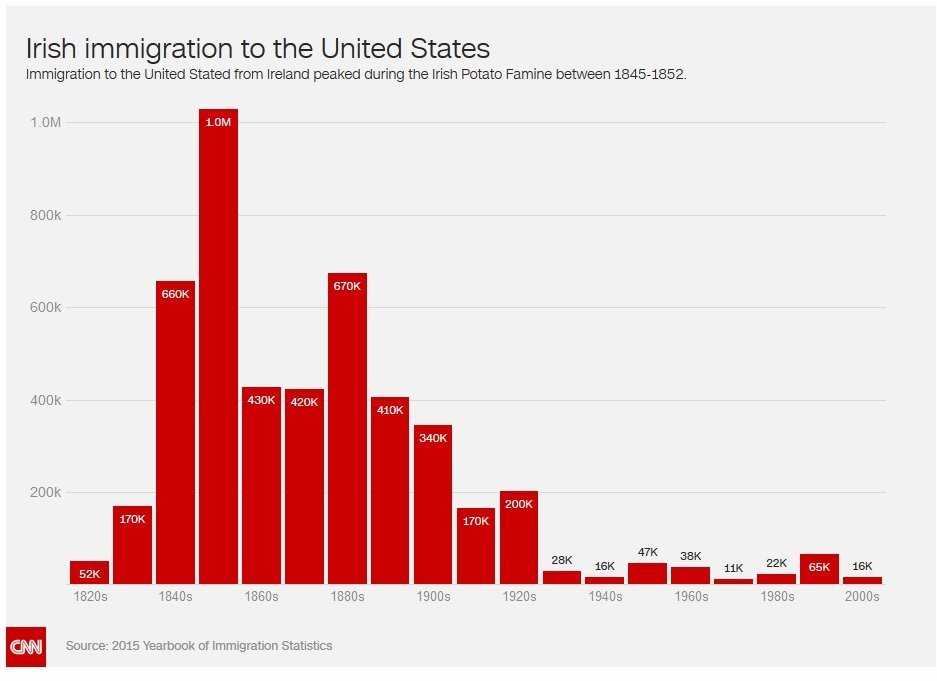

Ireland has long been sending its people to the US. During the decade after the Irish Famine, which happened in the mid-19th century, almost 2 million Irish people emigrated to the US — a quarter of the country’s population at the time.

The mass migration accounts for why more than 11% of Americans are of Irish heritage — among them White House advisers Kellyanne Conway, Steve Bannon and Sean Spicer.

But famine is long gone from Ireland. And despite the effects of the 2008 global financial crisis, Ireland has one of the highest standards of living in the world.

According to the United Nations Human Development Index, Ireland ranks in 6th place, ahead of the US in 8th and well ahead Mexico, which is ranked 74th.

It’s something that’s not lost on Shauna.

“There’s nothing stopping me from going home. I have family, support, it’s not that I can’t go home, it’s that I can’t come back.”

The situation is more complicated for undocumented Irish people who have children.

Back at the Aisling Center in the Bronx, Orla Kelleher says they are most anxious about Trump’s presidency.

“A lot of people have been here undocumented for more than half their life,” she says.

“If you see this as home it’s difficult to see where your future lies and having to uproot your family and start a new life somewhere you haven’t lived for years.”

Irish America

Ciaran Staunton, a veteran of the Irish lobby for immigration reform in the US, says most of the undocumented Irish are from rural parts of Ireland where employment is more difficult to come by.

“The vast, vast majority of undocumented Irish here are from parts of Ireland where there are not a lot of jobs. And most undocumented here are doing jobs that Americans don’t want to do.”

Earlier this month, Irish government figures showed that unemployment in the country had dipped to a nine-year low.

“That’s because most of the unemployed people [in Ireland] moved to America,” Staunton quips. “Almost 10% of the population of Ireland left in five years. Many of them ended up in cities here.”

On Thursday, as the Irish of Woodlawn pickup their corned beef from Oliver Charles, President Trump will host Ireland’s Taoiseach, or prime minister, Enda Kenny for the annual St Patrick’s Day festivities at the White House.

For decades, Irish leaders have used the meeting to ask for visas for undocumented Irish people in the US.

In the past, exceptions were granted — the Morrison and Donnelly visas of the 1980s and 1990s, named after the congressmen behind them, gave Irish citizens an advantage over some others seeking the American Dream.

“Irish immigrants fought in the revolution, the civil war, every battle, have more Congressional medals than any other. We’re no better than anyone else, but we’re no worse than anyone else either,” he says.

But Staunton isn’t looking for special exemptions just for the Irish, he hopes to see comprehensive immigration reform across the board.

“It’s the one law that affects everyone, we’re all in the same boat on this.”

“The problem at the moment is that there isn’t a path to citizenship, and if people overstay their visa they are banned,” he adds.

Hypocrisy

Staunton’s stance may represent an evolution in the campaign for the Irish undocumented, a move towards an approach that tackles immigration reform for citizens of all countries.

In his meeting, Taoiseach Kenny is expected to speak to President Trump about the undocumented Irish, though whether he’ll ask for a special solution for Irish citizens is not clear.

Fintan O’Toole, one of Ireland’s most prominent social commentators wrote in The Irish Times last week that there “is tacit racism in the appeal to Trump to make Irish migrants a special case.”

That may be the view of some in Dublin, but not all Irish-Americans.

“I have family here, second and third generation Irish. Their family came here as immigrants once,” Shauna says. “They’re the first to put on their green T-shirt on St Patrick’s Day, but at the same time will turn around and say ‘get every undocumented immigrant out of this country.'”

“I turn and look at them and say, I’m undocumented,” she says, “they don’t see it that way because I’m not brown and I’m not from Mexico, they see me differently. It’s disgusting.”

Life in President Trump’s America has prompted Shauna and her boyfriend, also undocumented, to consider a route so many other undocumented Irish have taken: marrying an American friend to get a green card.

“I’ve started thinking about setting up a family, but there’s a lot of risk to that when you’re illegal,” she says.

“Maybe I’ll go home one day, but this feels like my home now.”