It’s a dream many city-dwellers long for: moving to a spacious house surrounded by greenery in the countryside, where they plan to raise their family.

In 1996, Heather Shepherd, now 50, and her family did just that. Moving away from the congestion and noise of their north London home, they migrated to a 17th-century farmhouse that they would renovate and make their sanctuary.

Their village near Shrewsbury in Shropshire had just 70 residents, according to Shepherd, whom they would get to know well.

But two years later, not long after work was completed on their rural home, they got a sign of what it really meant to live in their new village: It was prone to flooding.

“We were about to get everything back to normal and have everything done, but the flood stopped everything,” Shepherd said. “It was frustrating.”

Her experience would make Shepherd realize not only the economic and physical repercussions this form of natural disaster would have on both her and her family, as they risked losing everything, but also the effect it would have on her thinking — her mental health.

With floods — as well as storms, heat waves and droughts — expected to increase in frequency thanks to climate change, the impact such trauma may have on the minds of those affected is something doctors, policymakers and governments are considering when planning services to help populations at-risk.

A fear of water

On this occasion, in 1998, Shepherd’s home was somewhat spared: Only parts of the house were flooded, and no furniture was ruined. Their new walls and floors were mainly affected. Others in the village were not as lucky, hinting at what was still to come.

Two years after that, in 2000, the real flood hit.

“We could hear the water from three miles away,” Shepherd said, likening the sound to that of a thundering waterfall, drowning out your voice. “It was that sort of sound, and you knew it was coming your way.”

That fall was the wettest on record to that point all over England, Wales and Northern Ireland, leaving many towns — including Shrewsbury — flooded. Though the town has a history of flooding, if rainfall and storms continue to increase over time, as predicted by global warming, so will water levels across the country, exacerbating the vulnerability of already at-risk towns, like Shepherd’s.

A flood warning had been issued by the UK Environment Agency, giving Shepherd’s family two hours to get ready. With her husband and two sons, she frantically worked to prepare and protect their home.

They lifted furniture till it almost touched the ceiling; hid boxes, valuables and treasured possessions upstairs; and even left their chickens to neighbors’ care and sought temporary homes for their cats and dogs.

“It was a race against time,” Shepherd said. “There was no time to think or calculate. … You just work like there is no tomorrow.”

Then, the flooding arrived, and the family could only stand in 2-foot-deep water and watch things float into their home.

When they left to stay with a neighbor who owned a more modern — and elevated — house, they found the water shoulder-high at the end of their drive. In the darkness, they were left only to imagine the damage being done to their home.

“That’s when it really hits you,” Shepherd said.

Even 17 years later, the memory brings tears. “You feel like a homeless person,” she said. “Your safe place has gone.”

The family of four lived in a recreational vehicle on the surrounding farmland for more than a year after the flood, while they dealt with insurers and builders who would eventually restore their home.

Their finances were hit hard, and daily life was a challenge. “All that we had worked for was completely destroyed,” Shepherd said.

According to Shepherd, her village was also flooded in 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2005, though her house was not directly affected in those years. She also now has a flood plan that outlines everything she needs to do if this were to happen again.

They were almost struck by the extreme weather seen in the UK in 2014, which saw major storms hit the country at levels not seen in the country for over 20 years.

Despite her experience and level of preparedness, she will never shake the feeling that it could happen again. In fact, she admits, it most probably will.

It’s just a question of when.

The mental cost of loss

“One of the major health effects of flooding seems to be the mental health aspects,” said James Rubin, a psychologist at Kings College London whose recent research looked into the psychological impact of people both directly and indirectly effected by floods. “There are a whole host of stressors around it,” he said.

These types of natural disasters are expected to rise in frequency due to climate change, and Rubin feels that the mental health aspect deserves more attention.

“Preventing (climate change) from happening, from worsening and intervening is really important,” he said.

Climate change is predicted to bring more than just floods: There could be heat waves, sea level rises causing loss of land, and forced migration and droughts affecting agriculture and the farmers producing it. And with these concerns comes a plethora of issues plaguing the human mind, such as depression, worry, anxiety, substance abuse, aggression and even suicide among those who cannot cope.

“If you don’t resolve them, these conditions don’t necessarily go away,” Rubin said.

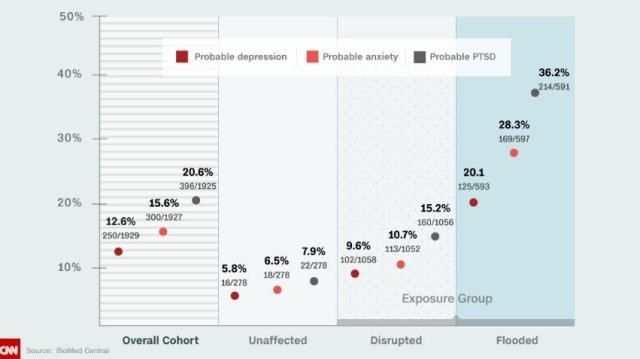

To find out the extent of this psychological burden, he focused in on flooding in one study and sent surveys to more than 8,000 people living in areas affected by floods in 2013-14, looking for signs of conditions such as depression and anxiety.

More than 2,000 people responded and were split up by their level of exposure — direct, indirect or not at all — and the types of conditions they were perceived to have, based on their answers.

“What you see is a gradient,” Rubin said. “Among the groups that were flooded, they had the greatest mental health problems.”

Among direct flood victims, 20% had been diagnosed with depression, 28.3% with anxiety and 36% with post-traumatic stress disorder. Among those disrupted (meaning their area was flooded but not their home), the team found almost 10% to have depression and 15% with PTSD. Those unaffected showed just 6% depression and 8% PTSD.

The findings were surprisingly high and not unique to this research, said Rubin, who now wants mental health to be made a priority when helping victims of any natural disasters.

He recommends that adequate mental health services be provided as standard parts of a response effort and that risk factors be identified to help protect people from developing any of these conditions in the first place, such as helping people who have been cut off from social support services or preventing extensive damage to homes.

“The worse the damage, the more likely a person is to have a mental health problem,” he said.

Shepherd and her family deal with their situation differently. Her husband prefers to deny the problem and asserts that a flood will not happen again, while she spends her Octobers thinking about the potential for disaster and how she could better prepare her home. “Everything I do, I need to think ‘flood,’ ” she said.

She has also made herself more resilient and informed by working for the National Flood Forum, a UK charity dedicated to supporting and representing communities and individuals at risk. “That was my way of coping,” she said.

But the feelings will always be there — worry, anxiety, fear — feelings many people not just around the world are experiencing as they think about the future of the Earth.

Environmental stress

“Stress has clear physiological effects,” said Susan Clayton, professor of psychology at Wooster University in the UK, who also believes that disasters such as flooding, heat waves and drought have a significant impact on the state of mind of millions around the world.

Through her research, she has reviewed studies on the impact of weather and changes in climate on people’s health, both physical and mental.

“Some things we know well; others, we speculate,” she said.

Clayton believes that when dealing the mental health aspects, climate change can be broken down into three main categories: natural disasters such as floods and storms, slower changes such as an increasing global temperature, and the loss of social networks or social capital.

With the slower changes come consequences such as aggression and violent behavior associated with higher temperatures, isolation and depression linked to forced migration and landscape changes, and the overall impact of stress.

In terms of higher temperatures, “research suggests we are less tolerant of other people,” Clayton said. “Migration is associated with all sorts of problems … and much higher levels of mental health issues.”

Many populations around the world face the threat of forced migration because their land is no longer inhabitable, including in Bangladesh, certain islands in the Pacific and Indian Oceans and in communities in Alaska and Louisiana. One island off the coast of Louisiana, Isle de Jean Charles, in the US has lost 98% of its land mass to rising sea levels and has been sinking since 1955.

Worry is yet another common element. “People worry about climate change,” Clayton said, fueled by the potential for effects on the economy and security, as well as the feeling that it’s beyond an individual’s control. “We expect there will be impacts of this worry but don’t yet know what they will be.”

A report by the European Perceptions of Climate Change project, published last week, found significant levels of worry and anxiety in populations in Norway, France, the UK and Germany who believed that negative consequences were affecting them and that more would come due to climate change.

France was one of the most affected countries during the heat wave that hit Europe in 2003. It killed more than 20,000 people on the continent, according to the UK Met Office, 15,000 of them in France.

Both Clayton and Rubin believe it’s crucial to look further into this field of research and make it a priority, as the repercussions will go far beyond individual families and communities.

“If people are very depressed, they’re not going to be able to work effectively,” Clayton said. People are then more likely to take up risky behaviors such as overeating and substance abuse. “If people are not going psychologically healthy, that is going to impact (society),” she said.

It’s even more true in developing countries, Rubin said.

“If you have even fewer resources to fall back on,” he said, “I can imagine the impact would be worse.”