A New York jury, with the conviction Tuesday of a bodega clerk in the 1979 kidnapping and killing of 6-year-old Etan Patz, brought to a close what a prosecutor called one of the city’s “oldest and most painful unsolved crimes.”

The guilty verdict against Pedro Hernandez, 56, in connection with a murder that sparked an era of heightened awareness of crimes against children, marks the end of an agonizing wait of nearly 40 years for Etan’s parents.

“The Patz family has waited a long time, but we’ve finally have found some measure of justice for our wonderful little boy Etan,” his father, Stanley, said.

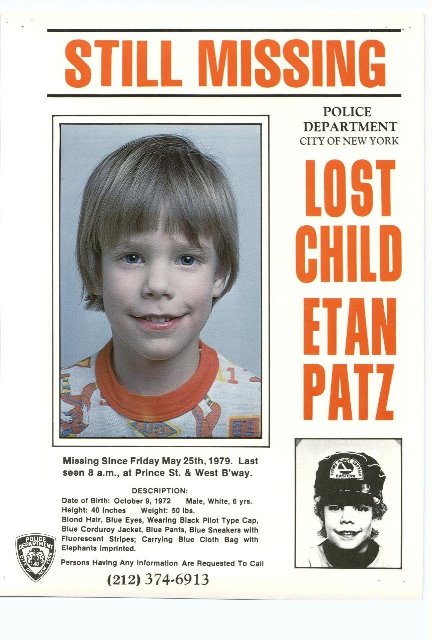

Etan disappeared on May 25, 1979, as he walked to a school bus stop. In the early 1980s, his photo appeared on milk cartons across the country, the first time the method was used to help locate missing children.

Hernandez, who was convicted after the jury deliberated nine days, faces a maximum sentence of 25 years to life in prison at sentencing later this month.

“The abduction … awakened the nation to child abduction and helped change the way law enforcement investigates these crimes,” said John F. Clark, CEO and president of The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

“NCMEC is here today — and America’s children are safer — because of Etan and other children whose abductions and killings launched a national movement.”

Hernandez was previously tried for the same charges in 2015, but was spared a conviction when a lone holdout on the jury led the judge to declare a mistrial.

Prosecutors this time convinced a Manhattan jury that Hernandez lured Patz into the basement of a bodega on the corner of West Broadway and Prince Street with the promise of a soda.

At both trials, the state used Hernandez’s own words to both investigators and mental health experts to secure a conviction, despite a lack of a forensic evidence connecting him to the crime.

Jury foreman Thomas Hoscheid told reporters, “Constructive conversations, based in logic, that were analytical and creative and adaptive, compassionate … and ultimately kind of heartbreaking” guided the panel through what he said were difficult deliberations.

In the basement, prosecutors said, Hernandez choked the boy to death and put his body in a plastic garbage bag that he concealed inside a cardboard box.

Hernandez eventually left the box with other trash in an alley more than a block from the store.

Defense attorney Harvey Fishbein has long maintained his client has an “IQ in the borderline-to-mild mental retardation range” that made him susceptible to a false confession. He vowed an appeal.

“There is a very good chance there will be a third trial,” said Fishbein, CNN affiliate WABC reported.

Hernandez confessed to police after a 7½ hour interrogation, but his lawyers said he made up his account of the crime due to his severe mental illness. Hernandez has been diagnosed with schizotypal personality disorder, one of a group of conditions informally thought of as “eccentric” personality disorders.

Juror Mike Castellon called the mental health issue “a red herring.”

“We decided he has that illness,” he said of the schizotypal personality disorder. “But that didn’t make him delusional. We think that he could tell right from wrong. He could tell fantasy from reality.”

Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. said in a statement Tuesday: “Etan’s legacy will endure through his family’s long history of advocacy on behalf of missing children… This case will no longer be remembered as one of the city’s oldest and most painful unsolved crimes.”

Etan’s case raised awareness

Etan’s remains have never been recovered.

Since their young son’s disappearance, the Patzes have worked to keep the case alive and to create awareness of missing children in the United States.

The number of children who are kidnapped and killed has remained steady — it has always been a relatively small number — but awareness of the cases has skyrocketed, experts said.

The news industry was expanding to cable television, and sweet images of children appeared along with distraught parents begging for their safe return. The fear rising across the nation sparked awareness and prompted change from politicians and police.

In 1984, Congress passed the Missing Children’s Assistance Act, which led to the creation of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

President Ronald Reagan opened the center in a White House ceremony in 1984. It soon began operating a 24-hour toll-free hot line through which callers could report information about missing boys and girls.