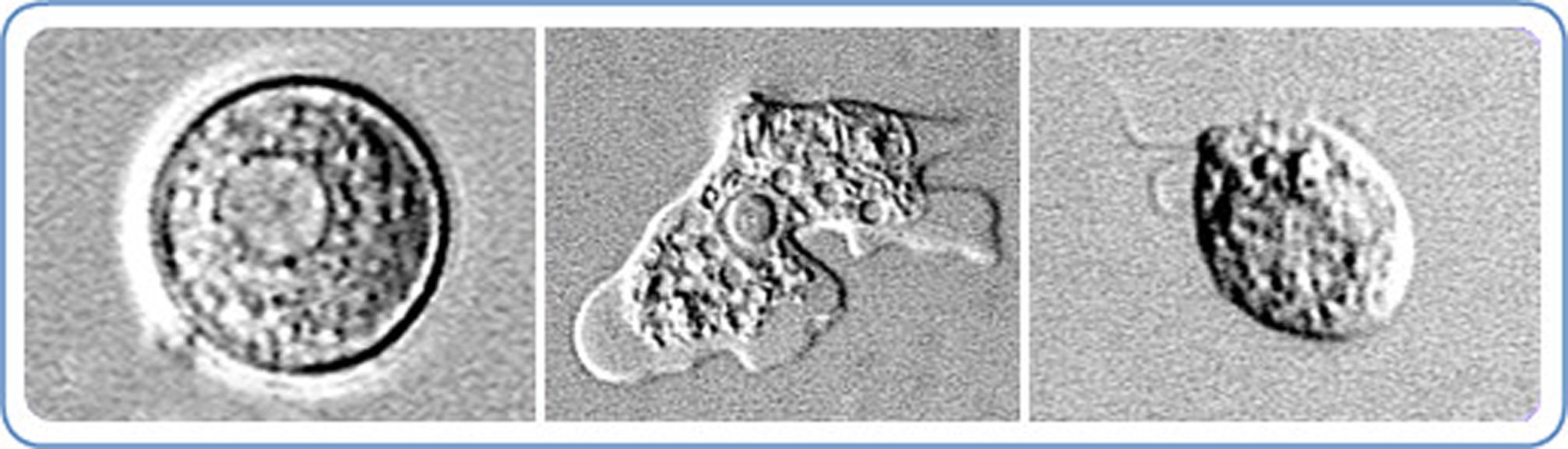

Levels of the brain-eating amoeba Naegleria fowleri that killed an Ohio teen were unusually high in water samples taken from the U.S. National Whitewater Center, and were likely caused by the failure of the water sanitation system, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced this week.

All 11 samples from the white water area of the park tested positive for the potentially fatal organism, the CDC said. Other samples from the nearby Catawba River were negative, although the amoeba was found in one sample of riverbank sediment.

“Our findings here are significant,” said Dr. Jennifer Cope, an infectious disease physician at the CDC. “We saw multiple positive samples at levels we’ve not previously seen in environmental samples.”

The amoeba were likely able to grow to such concentrations because of the amount of dirt and debris in the water, which turned the water “turbid” or murky, and interfered with the effectiveness of the sanitation process, Cope said.

“When you add chlorine to water like that the chlorine reacts with all that debris and is automatically consumed,” explained Cope. “It is no longer present to inactivate a pathogen like Naegleria.”

Cope said the same is true about the UV light sanitation system at the water park. “If you’re passing turbid water through UV light, the rays cannot inactivate pathogens,” she said.

Eighteen year-old Lauren Seitz, of Westerville, Ohio, died June 19, just three weeks after graduating from high school and about a week after returning from a white water rafting trip on at the National Whitewater Center just outside Charlotte, North Carolina.

While the deadly amoeba thrives in warm water environments such as lakes and rivers, infections only occur when water is forced up the nose, allowing the organism to travel up the nasal passages to the brain. That likely occurred when Seitz’s raft overturned on the rapids, which was the only such exposure Seitz had before dying, Cope said.

The Charlotte based park boasts that it is ‘world’s largest man-made whitewater river’, and is one of a growing number of man-made white water systems often created for Olympic training and competition. In April, the U.S. canoe and kayak competitors held qualifying trials there, as they did before the 2012 and 2008 Olympics.

It’s also one of only three such systems in the U.S. that are not required to be regularly tested for pathogens, said Cope. According to local health officials, that’s because it’s viewed as more of a river, even though the park is made of concrete channels that recirculate 12 million gallons of water from the city’s municipal water system, some water wells, and rain.

“They [the center] were not required to be a regulated facility, but that is being questioned for the future,” said Mecklenburg County Medical Director Dr. Stephen Keener in a press conference.

“We don’t know very much about how Naegleria lives and grows in systems like this,” said Keener, “but factors such as soil runoff, uneven surfaces, stones on the bottom where slime can grow, along with shallow channels that allow water to warm quickly on hot days, makes it a unique environment.”

“There will be challenging conversations ahead with various experts in aquatic sector and environmental engineers,” agreed Cope,” about the best ways to address the situation.”

The National Whitewater Center is open for all activities over the 4th of July holiday except for the white water channel. That section closed June 24 after initial tests discovered the brain eating amoeba in the water supply.

Officials say a plan to remediate the channel is underway, once they understand more about the safest way to cleanse the system of the amoeba, without putting sanitation workers at risk.