Florida alligators have a bad rep right now.

After one of the reptiles killed 2-year-old Lane Graves at a Disney resort this week, people are understandably wary of the predators.

But the truth is that while they’re doubtless dangerous, attacks on humans are rare, as numbers from the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission demonstrate:

— There are 1.3 million alligators in the state, roughly one for every 15 residents.

— Despite their prevalence, alligators have attacked only 383 people since 1948. Of those, 126 were minor attacks, meaning the victims didn’t require first aid. That means, in almost seven decades, fewer than four attacks a year were serious.

— In that same timespan, there were only 24 fatalities, fewer than half of the death toll wrought by the Pulse nightclub shooter just days before young Lane was tragically killed.

Floridians are astutely aware of the dangers they pose and, in fact, have embraced the animals, making them a central part of the state’s identity.

No, they’re not the draw of theme parks or the Gulf Coast or South Beach, but Florida is aware the beasts carry a certain mystique and has capitalized on it in many ways.

Here is a look at how alligators are as much a part of Florida as oranges, palm trees and hurricanes.

Feedings

As you pull into The Black Hammock in Oviedo, it feels like something out of a Carl Hiaasen novel: Locals and tourists swig cold beer beneath palm trees on a Lake Jesup peninsula hosting a fleet of airboats covered by a tin roof.

Alligators bask in concrete enclosures, as colorful parrots caw and say hello from their chain-link aviaries. Alligator sculptures and paintings can be found throughout the compound, which includes a restaurant, gift shop and the Lazy Gator Bar.

A big draw is the alligator feedings, said Samantha, 24, a gift shop employee who asked not to give her last name. She’s been coming to Black Hammock with her family since she was 12 and began working there in October.

“You can hold the baby gators,” she said, pointing to a 2-foot female in the gift shop aquarium. “We’ve got Firecracker here and up at the restaurant we’ve got Max. … He gets a little cranky sometimes, but she’s the sweetest. You pull her out, she barely struggles at all. You lay her in your arm and she’ll just sit there, like a cat. You just pet her.”

For $2, you can buy a plastic cup of hot dog chunks, which you attach to a wire at the end of a cane pole and drop into one of the enclosures. As whimsical as it sounds, it gives you a sense of the animal — its lethargy, poor vision and ineptitude at chewing.

Airboat tours

Like The Black Hammock, many outfits offer airboat tours into gator country. The best time to see them is during the cooler spring months.

Scott Vuncannon of Marsh Landing Adventures in St. Cloud has been giving the tours for 12 years, and despite the abundance of wildlife in these ecosystems, tourists often tell him the same thing.

“Most of them want to see an alligator in the wild. They want to see something that will come up and say hi,” he said.

Vuncannon’s happy to oblige, he said.

“Everybody gets one guaranteed. If I’ve got to keep you out here the rest of the day, you’re going to see one alligator,” he promised.

Wrestling

The Seminoles claim alligator wrestling began with their tribe. According to an Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum blog post, it began with Seminoles hunting the animal for food.

Billy Walker, alligator wrestler on the Big Cypress Reservation, explained in the post — recalling what his grandfather told him — that tourists would see the native Americans tying alligators to a post and thought they were wrestling them. The tourists threw money, Walker said.

The blog post goes on to city the book, “Enduring Seminoles: From Alligator Wrestling to Ecotourism,” which says the practice began in 1910 on an alligator farm in Miami.

Today, there are plenty of places in the Sunshine State to see wranglers perform the feat.

Marketing

It’s tough to go far in Florida without witnessing the advertising prowess of the state’s native crocodilian.

While some applications seem perfectly appropriate, others seem a stretch.

What led proprietors, for instance, to call their Orlando business Gator Screen Inc.? No telling. The owners didn’t return a call and email seeking an explanation.

There is a lawnmower parts company in Longwood that co-opts the name. That makes a little more sense. There’s a tire shop in Oviedo. There are LOTS of bars and restaurants. Perhaps there is no rhyme or reason. Floridians just like their gators …

Mascots

… Which probably explains why the creature is such a popular mascot for the state’s schools.

Baker High, Wewahitchka High, Land O’ Lakes High, Escambia High in Pensacola, Everglades High in Miramar, Island Coast High in Cape Coral — Gators, all of them.

But perhaps there is none more famous than the Gators from the University of Florida, who call their homefield, Ben Hill Griffin Stadium, “The Swamp.”

How did the state’s flagship university come to be known as the Gators? After the school formed its football team in 1907, local drugstore owner Phillip Miller wanted to order pennants for the university’s fans. But the school had no mascot.

“Miller thought of the alligator, a native Floridian animal, and went back to Florida putting the gator paraphernalia in his store using orange alligators on blue banners. The rest, as they say, is history,” according to the university.

Viral intrusions

YouTube is rife with strange alligator encounters from Florida. You have the gator attacking a truck, and myriad videos of gators taking dips in swimming pools and invading porches.

But perhaps one of the most shocking videos is of a massive gator trotting across a gold course in Palmetto.

Ken Powell, the regional manager in charge of the Buffalo Creek Golf Course, said the course held a contest and selected the name Chubbs, after the golf instructor played by Carl Weathers in the movie, “Happy Gilmore.”

Powell took over management of the course five years ago, he said, and though video of the dinosauresque reptile recently went viral, there were pictures of Chubbs on the course when Powell arrived.

“Everybody knows he’s here,” he said.

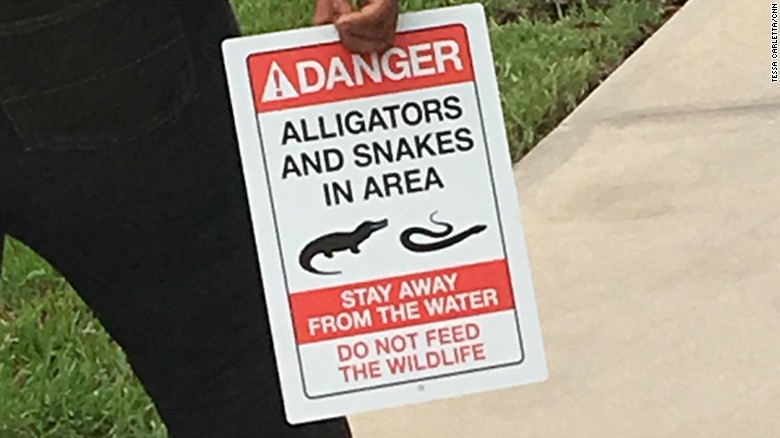

There are signs on the course warning golfers to be vigilant, he said, but there’s never been an attack. Actually, you hardly see Chubbs, or any other alligator, out and about, except during the spring mating season, he said.

“He’s in a perfect ecological location,” Powell said. “There’s lots of food in the (nearby) reservoir, and he goes from pond to pond during mating season.”

Food

When you have 1.3 million alligators walking around, it’s no surprise people eat it.

While the most common variation is fried tail, chefs across the state have demonstrated their culinary creativity in cooking up the critter.

The Deck in Fort Lauderdale serves up gator chowder (and, occasionally, omelets), Evan’s Neighborhood Pizza serves up a gator pie with sausage and peppers, The Pit Bar-B-Q in Miami boasts a gator burger, Skipper’s Smokehouse in Tampa will fix you some gator ribs and the Pink Gator Café at the Myakka River State Park in Sarasota is famed for its alligator stew.

Bon appetit.