Demonstrators marched through the streets of Baltimore, as they had for the past week. Devin Allen, then an amateur photographer, was among them.

Little did he know he was about to take a picture that would change his life and show the world what he was seeing in Baltimore.

On April 25, 2015, the crowd marched from Gilmor Homes in the Sandtown neighborhood where 25-year-old Freddie Gray had lived and had been arrested. He was put in a police van on April 12 and died of a spinal injury one week later.

They marched to Baltimore City Hall. Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake said most protesters were respectful but a “small group of agitators intervened.”

They marched through downtown toward the city’s famous baseball stadium, Camden Yards. When demonstrators got to the stadium, tensions escalated and some people threw what appeared to be water bottles and other objects at the police, who wore helmets and stood behind metal barricades.

Allen said he heard racial slurs yelled at protesters from baseball fans, which he believed sparked the violence that would follow.

“This is where I snapped the cover of Time magazine, this is where they destroyed the police cars … this is where everyone was completely boxed in by the police officers,” recalled Allen.

His blunt image from that day, of an African-American man running in front of a phalanx of police officers in riot gear, is one of only three photos by a nonprofessional photographer to ever grace the cover of the magazine. It went on to be chosen by the editors of Time as one of the top 10 magazine covers for 2015.

“It was a crazy day. It was the beginning, and this day changed my life,” Allen said.

That day also changed the way he perceives the world, the style of his work and inspired him to pursue photojournalism, he said.

“[It was] a spark. A new spark, a new light, a new set of eyes that my work has been directed through following this story. Not just the story of Freddie Gray, but the story of Baltimore also,” Allen said.

On April 25, Allen felt his calling stronger than ever. He said he could hardly believe so much was happening — the police, the crowds — and there he was, snapping photos. At one point in the chaos, Allen was nearly trampled underfoot, but he said a police officer helped him get up and out of the way.

Allen said he wanted to get his photos showing what was happening out to his community as soon as possible to “beat media to the punch,” so he uploaded them on social media.

Allen’s photography, posted to his Instagram and Twitter accounts, became a major news source for many in the Baltimore community.

“The next thing I know, the pictures just went viral, within an hour. I saw like a thousand retweets; everyone was reposting it,” he said.

‘I was going to capture every moment’

Allen, 27, grew up in Baltimore, not far from Gray. Allen described his hometown as a small city where family and neighborhood connections run deep.

“You know someone’s cousin, someone’s friend knows this friend. It’s a very small city. So when Freddie Gray passed, I didn’t know him personally but I know people that knew him,” he said.

Gray’s arrest was recorded by a bystander, and the video made its way to many in the community, including Allen, via group text, passed from one group of family, neighbors and friends to the next.

At that point, Allen said, knowing his community and its strained relationship with police, he sensed that something was going to happen. He grabbed his camera and started following the story.

“Being from Baltimore, I know the streets, I know people here. So I was going to capture every moment,” he said.

Allen documented everything he saw. Alongside journalists from major news organizations from around the world, like CNN, the hometown photographer didn’t back down.

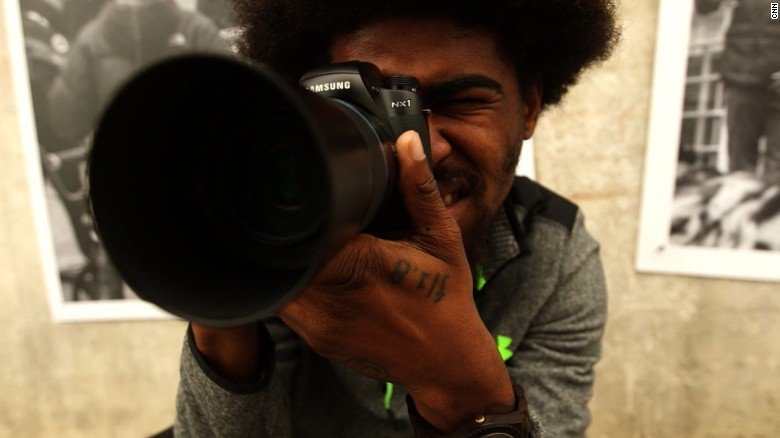

“I don’t like zoom lenses. I don’t want to sit back across the street,” Allen said. “I want to be in the mix. I want to feel that energy, that rush.”

To Allen, many in Baltimore felt a rush, too. In the wake of racially charged clashes with police in protests across the country and the deaths of black men including Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Eric Garner, the death of Gray stirred a great emotion in Baltimore.

“People were starting to understand what was going on,” Allen said. “It hit home I think with Freddie Gray, it woke a lot of people up … that could have been anyone’s kid,” said Allen.

In the months since the marches and demonstrations, Allen is looking forward, both for Baltimore and in his own life.

“I just thought I was just taking good pictures and I just was like, well, I hope these pictures get into the right hands or the right people see it,” Allen said. “I never thought this would be born from that at all.”

Allen has spoken to community groups and sat on discussion panels on the struggles in Baltimore and about his photography. He’s been on CNN and featured in various news outlets from New York Magazine to The Washington Post. His work is currently exhibited at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum in Baltimore and another show is scheduled in Philadelphia for late January. A retrospective of Allen’s work was shown at acclaimed pop-up photography exhibition, Photoville, in New York. His work is in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture opening in Washington in fall 2016.

A different side of his city

But he hasn’t forgotten what got him here or what motivated him. Allen has starting a program teaching photography to inner-city children. He started a campaign on the crowdfunding platform GoFundMe and the response was big. Among the donors is hip hop entrepreneur Russell Simmons.

Now the program continues to grow, from the Penn North “Safe Zone,” a dedicated safe place for young people in the Sandtown neighborhood, to Baltimore city schools. Allen said the children are documenting everyday life at their school and working toward an exhibition as well as an online gallery of the students’ work.

Baltimore-based Under Armour approached Allen to sponsor his photography. The sports apparel and accessories maker also donated to Allen’s youth programs and sent him to Asia to photograph basketball player Stephen Curry. He went to Tokyo, Beijing, Shanghai and the Philippines. Allen traveled to Austria and visited a refugee camp where people from Syria are trying to get to Germany. This has had a big impact on Allen, who previously had never traveled outside of the United States.

“Being able to go to these communities, I’m basically seeing all these different struggles,” Allen said. “You know, I was only activist for one movement and now I stand for multiple movements. I’m becoming more, the more places that I go.”

These days, Allen and Under Armour are working on a deal for him to shoot for the company full time.

Allen still documents Baltimore to show a different side of the city, to show, he said, his community.

‘I’m not too small to make a change’

In December, the trial of Officer William Porter, the first of six city police officers charged in the death of Gray, resulted in a mistrial and in January, the trial of the next officer, Caesar Goodson Jr. was postponed. Allen saw a community that he says learned from some of the chaos in the demonstrations of April and still watches the case closely. He saw how the city came together to clean-up and create change following April’s unrest. Allen points to local prayer circles and even pickup football games with police officers and civilians standing together, calling it a beautiful example of how the community has come together. He encourages the community to stay focused on creating change in the city and to keep working to honor the legacy of Gray.

“Don’t just protest,” Allen said, “Bring this to everyday life. … Either we’re going to progress or we’ll move backwards.”

Allen said he will continue to do his part to document the story.

“Now I understand how powerful an image can be. I understand I’m not too small to make a change. I’m still an activist. I’m still a protester, you know. But at the same time, I’m in a different place now,” said Allen. “You know, I have a lot of attention on me, so I’m able to give back to the community. I’m able to inspire the youth and sway, you know, them with my words and by telling my story. … Devin Allen is — you know, everyone calls me the ‘Eyes of Baltimore.'”