The Paris terrorist attacks have intensified a debate in Washington over whether the United States should allow Syrian refugees to enter the country.

Following reports that one of the terrorists involved in the strike entered Europe as part of a wave of Syrians fleeing the country’s civil war, Republicans on and off the campaign trail are pressing President Barack Obama not to accept the displaced people. Many Republican governors, meanwhile, have said they won’t allow Syrian refugees into their states.

Here’s how the refugee process works.

How do refugees come to the United States?

Potential refugees first apply for refugee status through the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the international body in charge of protecting and assisting refugees.

The UNHCR essentially decides who merits refugee status based on the parameters laid out in the 1951 Refugee Convention, which states that a refugee is someone who “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

If it’s demonstrated that the refugee in question meets the above conditions, the applicant may be referred by the UNHRC for resettlement in a third country, such as the United States, where he or she will be given legal resident status and eventually be able to apply for citizenship.

After the UNHCR refers a refugee applicant to the United States, the application is processed by a federally funded Resettlement Support Center, which gathers information about the candidate to prepare for an intensive screening process, which includes an interview, a medical evaluation and an interagency security screening process aimed at ensuring the refugee does not pose a threat to the United States.

The average processing time for refugee applications is 18 to 24 months, but Syrian applications can take significantly longer because of security concerns and difficulties in verifying their information.

Once they’ve completed that part of the process, the refugee is paired with a resettlement agency in the United States to assist in his or her transition to the country. That organization provides support services, such as language and vocational training, as well as monetary assistance for housing and other necessities.

What’s the security vetting process like?

Much attention has been focused on the security vetting refugees must go through before they come to the United States, particularly after it was revealed that one of the terrorists in the Paris attacks entered Europe through a refugee processing center.

Several federal agencies, including the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security, the Defense Department, the National Counterterrorism Center and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, are involved in the process, which Deputy State Department Spokesman Mark Toner recently called, “the most stringent security process for anyone entering the United States.”

These agencies use biographical and biometric information about applicants to conduct a background check and make sure applicants really are who they say they are.

The applicant is interviewed by a DHS officer with training in this screening process as well as specialized training for Syrian and Iraqi refugee cases.

And refugees from Syria actually go through another layer of screening, called the Syria Enhanced Review process.

“With the Syrian program, we’ve benefited from our years of experience in vetting Iraqi refugee applicants,” a senior administration official recently told reporters. “And so the partnerships we have today and the security checks we have today really are more robust because of the experience that we’ve had since the beginning of large-scale Iraqi processing in 2007.”

Another senior administration official noted that the refugee screening process is constantly refined.

What are the challenges associated with vetting these refugees?

Given the abysmal security situation in Syria and the fact that the United States does not maintain a permanent diplomatic presence in the country, it’s sometimes difficult for U.S. authorities to gather the information they need to thoroughly vet a Syrian applicant.

FBI Director James Comey hit on the issue at a congressional hearing last month, when he told lawmakers, “If someone has never made a ripple in the pond in Syria in a way that would get their identity or their interest reflected in our database, we can query our database until the cows come home, but there will be nothing show up because we have no record of them.”

This particularly comes into play when trying to evaluate an applicant’s criminal history.

“In terms of criminal history, we do the best we can with the resources that we have,” one senior administration official said.

Another official emphasized that the vetting process is a holistic one, and they try to take a broader view of an applicant with the available information they’re about to aggregate and verify.

How many refugees have been admitted to the United States?

U.S. government data shows that just under 2,200 Syrian refugees have been admitted into the United States since the civil war broke out in March of 2011, and the vast majority of those were in the last year.

The administration has acknowledged that processing resettlement applications is a slow and laborious task, which has kept the United States from accepting as many applicants as it would like to.

But the pace of admissions is growing as the United States commits more resources to the endeavor.

What do we know about the refugees admitted so far?

According to senior administration officials, more than half of the Syrian refugees admitted into the U.S. so far are children.

“Single men of combat age” represent only 2% of those admitted and the elderly comprise another 2.5%. The male/female breakdown is “roughly” 50/50.

The approval rate for Syrian refugees so far is a little over 50%, although the official noted that those not included in this pool include both rejected cases and pending cases, so the approval rate is expected to go up.

Where are these refugees?

The Syrian refugees who have been admitted into the United States so far are spread out over 36 states in 138 cities and towns.

California has accepted the most Syrian refugees (252), followed by Texas (242) and Michigan (207).

Fourteen states and the District of Columbia have not admitted any refugees, but that doesn’t necessarily reflect a lack of will. Resettlement locations are determined based on a number of factors, including family ties, the size of the local immigrant community and the ability of local resettlement agencies to accommodate new cases.

Officials also take into account the unemployment rate of the area to ensure refugees are able to find work and begin supporting themselves.

How many will be admitted in the future?

As the Syrian refugee crisis in Europe and the Middle East became more dire over the summer, the Obama administration decided to re-evaluate how many Syrian refugees could be admitted.

Ultimately, the President decided to set a goal of 10,000 for the current fiscal year, which goes until October 2016.

In order to accommodate these additional Syrian refugees, the administration upped the total number of refugees it would allow in FY2016 to 85,000, with plans to increase it to 100,000 in FY2017.

But there are significant challenges associated with increasing the quota.

As noted above, the vetting process for Syrian refugees is intensive and plagued by gaps in information.

In order to meet the 10,000 quota it has set, the administration will have to admit five and a half times more Syrian refugees in the coming year than it admitted in the previous 4½ years combined.

Who decides the quota?

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 sets fairly clear guidelines for how the government can set and change refugee admissions quotas.

Per section 207, the President has the authority to set the annual number, following “appropriate consultation” with members of Congress.

This is done at the start of the fiscal year but can be revisited midyear in cases where “an unforeseen emergency refugee situation exists” and the admission of refugees in response to that emergency “is justified by grave humanitarian concerns or is otherwise in the national interest.”

In that situation, the President can amend the number of refugees allowed prior to the start of the next fiscal year, again in consultation with Congress, essentially briefing the lawmakers.

My governor wants to stop admitting Syria refugees. Is that allowed?

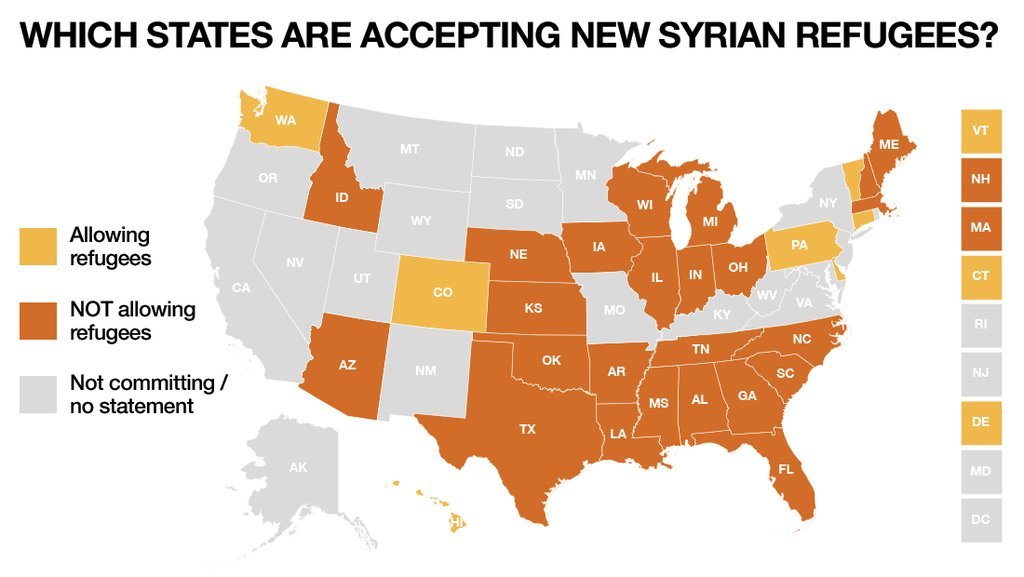

Over half of U.S. governors, most of them Republicans, announced in the aftermath of the Paris attacks that their states would not accept any further refugees from Syria. But it’s unclear whether they have the legal authority to do this.

“This is a federal program carried out under the authority of federal law,” one senior administration official noted, “and refugees arriving in the U.S. are protected by the Constitution and federal law.”

Refugees are required to adjust their status to become legal permanent residents of the United States within one year of their arrival, at which point they are free to move anywhere in the country, although the official noted some specific benefits may only be available in the state where they were originally resettled.

But experts tell CNN that while the states may not have the legal authority to block their borders, state agencies have authority to make the process of accepting refugees much more difficult by cutting state and local funding.

“I think the entire program is contingent on the support of the American people,” the official acknowledged. “It is contingent, as all programs in the United States government are, on funding from Congress.”

Now lawmakers are weighing in with proposals to block Syrian refugee funding entirely, which would have the effect of freezing their absorption.

This step presents its own challenges, since funding for Syrian refugees is allocated along with funds to support refugees from other countries.