On game day, 70,000 football fans pack Doak Campbell Stadium to watch Florida State roar to victory. I wait for the post-party quiet of the following morning to wander through campus with Maria, knowing that a return to this place could be risky.

At the main entrance to the university, we run into two high school students from Tampa posing for a photo in garnet and gold Seminole jerseys. They want to enroll at FSU one day soon, they say, their cherubic faces lighting up.

Maria was that way once: young and brimming with hope, excited to start the adult chapter of her life at a prominent state university bustling with students from all over the globe. In the fall of 1987, her mother dropped her off in this very spot, in front of the administrative offices housed in Westcott Building.

But college turned out to be a dark adventure.

Before she could finish her second semester, Maria was gang-raped on campus. Her assault made national headlines partly because the details read like sleazy fiction and partly because it involved one of the most prestigious fraternities on a football powerhouse campus.

It was a case I became intimately aware of as a journalist in Tallahassee at the time and one that I sympathized with as a former FSU student and campus rape survivor.

I expect the return to FSU to be a difficult journey — for both Maria and me. It is the first trip back to campus for us since our departures from Tallahassee. In the years since, many things have changed at America’s institutions of higher learning. Sadly, some have not.

Rape on college campuses was a serious problem then and remains one now. One in five college women said they were sexually assaulted, according to a Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation poll released last June.

It’s a problem highlighted in the film “The Hunting Ground,” which airs on CNN on November 19. The film delves into a connection between alcohol and sexual assault and explores a campus culture that protects perpetrators.

It also focuses on the stories of survivors who became activists and took the issue all the way to the White House and prompted a federal investigation of the handling of sexual violence complaints on campuses.

As the film demonstrates, the Internet and social media made it possible for rape survivors to connect with one another and find a modicum of comfort. Even power. When Maria and I were in college, that was not the case. We felt, and were, very much alone.

We both chose to keep silent about what happened, except in Maria’s case, the crime was so heinous that despite her unwillingness, the state pursued charges against her rapists.

Maria felt a thousand eyes on her. She bore the brunt of unkind comments. She came back to her dorm room one day to find this message on the white board on her door: Whore. She withdrew, rarely spoke about the incident and even tried to kill herself. She survived through the years, but only barely.

A couple of months ago, Maria and I watched “The Hunting Ground” together.

We sat at a desktop computer in a sterile hotel lobby, sharing a pair of earbuds. I used the left one and she, the right. It was the first time I’d met Maria in person, though I had spoken with her once on the phone a few weeks after her rape.

She watched the movie intently. I could see tears gathering behind her glasses and her hands trembling. A few weeks later, she agreed to go back with me to the scene of her attack. After 27 years, she was ready, she said, to come to terms with the incident that altered her life’s trajectory.

I understood all too well the significance of her decision. I, too, had only recently gone public about my rape after a reporting trip to my native India to find a woman named Mathura, a rape survivor who was at the heart of a groundbreaking case.

I regretted that the newspaper stories I edited about Maria’s rape had never given her voice. Throughout her ordeal and the months of court proceedings, she chose to remain anonymous. She was never named publicly and granted only a handful of interviews. The court records were sealed to protect her identity.

She agreed to speak with me on the condition that CNN not reveal her real name. She wanted to share her ordeal with other young women who have suffered rape or might be assaulted before they graduate.

“Maybe my story can help them in some way,” she said.

On this Sunday morning in October, a warm sun illuminates her golden hair as we meander down asphalt paths that connect FSU’s signature red brick buildings. I respect the courage it takes for her to stand with me on campus.

A little after 9, her smartphone lights up with a text from her boyfriend: “You’ve got this. I love you.”

Maria sighs. She came here, she tells me, to face the ghosts that haunt her. She wants to take her 18-year-old self by the hand, lead her through the places that were dark and let her know: “It’s going to be alright. You are safe.”

A slideshow of chilling images

From the main entrance of the university, we walk to a campus hangout where both Maria and I spent hours studying, the Sweet Shop.

We take a break on Landis Green, the Central Park of FSU. Maria sits on a bench before live oaks laden with lacy Spanish moss that falls from the branches like tears. She hides her eyes behind Jackie O. sunglasses and takes slow drags of her Marlboro Menthol 100; I sense her anxiety as memories flood her mind.

We decide to retrace the steps Maria took on a damp spring night in 1988, past the blocks that once housed a newspaper office where I worked and a JR market that sold Texas taters and $1.99 six-packs of Schaefer beer. We stand before an all-new Dorman Hall, tonier than the version where Maria lived. From her room, she could see a row of sorority houses that included Chi Omega, where a few years before Maria arrived at FSU serial killer Ted Bundy murdered two young women.

We look the other way down Jefferson Street and recognize a motel-style apartment building with jalousie windows and air-conditioning units overworked even this far into autumn. We laugh that the ugliest building of all survived the bulldozers.

Around the corner is the place where Maria went on her last night of normal.

The Pi Kappa Alpha mansion with the stately white columns is no longer there, but Maria can picture it clearly in her mind. She points to the spot where she was tossed like a piece of trash, badly bruised and unconscious, just one drink away from death.

There’s no clear storyline in her mind — there wasn’t then and there isn’t now. She sees a slideshow of chilling images, blurry and yet so vivid at times that she can feel it all again.

Wine, a blue room, cold tiles, running water, flesh. And force. So much force.

Maria liked to drink and dance at an after-hours bottle club called the Late Night Library. On the evening of March 4, 1988, she was there with her friend Sandra. It was Friday, and the indie bar was hopping.

Maria arrived at FSU shy and introverted. Her mother was an alcoholic, and Maria had started drinking in her senior year at a girls-only Catholic high school in Louisiana. At FSU, she rebelled. She thought alcohol helped her feel more comfortable, and she developed a penchant for partying and a reputation for being promiscuous. She had already had many beers by the time she ran into Daniel Oltarsh, a political science and economics major she’d met at a pig roast several months before.

Oltarsh was handsome in a bookish way with blond curly locks and trendy round glasses that framed his blue eyes. Most of all, he was a Pike.

Many of the men of Pi Kappa Alpha were well-heeled sons of prominent fathers. They wore starched Oxford shirts, double-breasted blue blazers and Rolex watches. Around campus, many considered them the kings of FSU’s Greek system, admired and reviled all at once.

Maria felt honored that someone like Oltarsh would talk to her. So when he invited her to a party that night at the Pike mansion, she was beside herself. She walked back to her dorm, changed into a three-quarter sleeve sweater and black pencil skirt and poured herself a tumbler of tequila. She took the drink with her on the short walk to the fraternity house at 218 S. Wildwood Drive.

Oltarsh was waiting for her on the columned porch. They went upstairs to his room. He managed to get a bottle of white wine and Maria drank more. It was past 3 in the morning.

“Where is the party?” Maria asked.

There was none.

The details of what happened next are culled from court files, including police interviews with Pi Kappa Alpha members and a grand jury report indicting 23-year-old Oltarsh and two other fraternity members: Byron Stewart, then 21, and Jason McPharlin, 18, who was visiting from Auburn University.

A fourth fraternity brother was given immunity in exchange for his cooperation with the investigation. The documents include his version of what happened as well as a statement from McPharlin.

Maria was so drunk she could barely stand up. She told police Oltarsh got “aggressive” with her in his room and forced her to have sex. He then took her to the shared bathroom. He let other frat brothers know there was a girl available for sex. It was called “pulling a train.”

The fraternity brother who was given immunity told police that Oltarsh was fondling Maria in the shower and that he joined them there. He and Oltarsh took turns having sex with her in the shower.

At some point, McPharlin went into the shower. He told prosecutors that he took his boxers off, got in the shower with Maria but did not have sexual intercourse with her. He got up and left after he saw Stewart, who he was not acquainted with at the time, come into the bathroom.

Fraternity brothers who spoke to police said Stewart, a former high school football player from Orlando, could not get an erection and bragged about using a Colgate toothpaste tube to violate Maria.

They called her obscene names and repeatedly told her she was in a house belonging to Sigma Chi, a rival fraternity. When they were done, they took her back to Oltarsh’s room and dressed her. Oltarsh used a ballpoint pen to write the words “Hatchet Wound,” crude slang for a woman’s genitals, on Maria’s right thigh. On the other, he scrawled the Greek letters of another fraternity, Sigma Phi Epsilon.

Oltarsh and McPharlin carried her by the arms and legs to the Theta Chi fraternity house next door and left her limp body in the hallway, according to the fraternity brother who cooperated with the police. They left her there with her legs spread, her skirt pulled up and her underwear down.

They then walked to the convenience store, the one that sold Texas taters, and Oltarsh used a pay phone to call the FSU police. He returned to his room on the third floor of the Pike house and watched from a window along with his accomplices as police officers and paramedics arrived at 5:30 in the morning. An ambulance sped Maria to Tallahassee Memorial Hospital.

Her blood alcohol level was recorded at .349, three times the legal limit in Florida and one 4-ounce drink away from alcohol concentration that could have proved fatal.

She spent most of the day in the hospital and was interviewed by a FSU police officer. Her recollection of her assault was not complete — at some point, she blacked out from the alcohol. Medical examinations determined she had been sexually violated by more than one person. She had scratches and abrasions on her body.

Later that day, she returned to Dorman Hall and stood in the shower, wanting desperately for the hot water to wash everything away.

She just wanted to forget it ever happened. Only 20% of campus victims from the ages of 18 to 24 report their assaults to their institutions or law enforcement agencies, according to the Department of Justice.

Maria did not want to press charges but District Attorney Willie Meggs did.

The grand jury concluded Maria was physically helpless and was unable to resist and on May 18, 1988, Oltarsh and Stewart were indicted on a sexual battery charge. Oltarsh and McPharlin were charged with culpable negligence and kidnapping in connection with moving Maria. In addition, Oltarsh faced charges related to writing on Maria’s thighs and giving her alcohol as a minor. McPharlin was charged with possession of alcohol by a minor.

The three maintained their innocence, saying that Maria was a willing participant.

But Meggs felt Pi Kappa Alpha was covering up a crime.

The indictments were largely based on the testimony of the fraternity brother who was given immunity and not charged in exchange. It was believed to be the first time members of a fraternity on a major university campus faced prosecution in a gang rape.

Meggs understood the concept of fraternal loyalty from his service in the Marine Corps and years spent pounding Tallahassee pavements in his first beat as a cop. But he despised how the Pikes closed ranks around their own and had to be subpoenaed to answer questions.

Even after all these years, Meggs gets emotional talking about Maria’s case.

“Their conduct was so egregious,” he tells me. “It was unconscionable.”

“I was really disappointed that there wasn’t one red-blooded American in this fraternity who said: ‘Stop it.’ That not one young man asked: ‘What if that was my sister?’ “

It didn’t matter to Meggs, his assistant state attorneys who argued the case or the investigating police officers that Maria drank too much. Or that she was known as a party girl. She was not conscious enough to have consented that night.

Even “a prostitute can be raped,” he says, if the sex act is not consensual. And in Maria’s case, he says, she “was in such a state that she could not say ‘no.'”

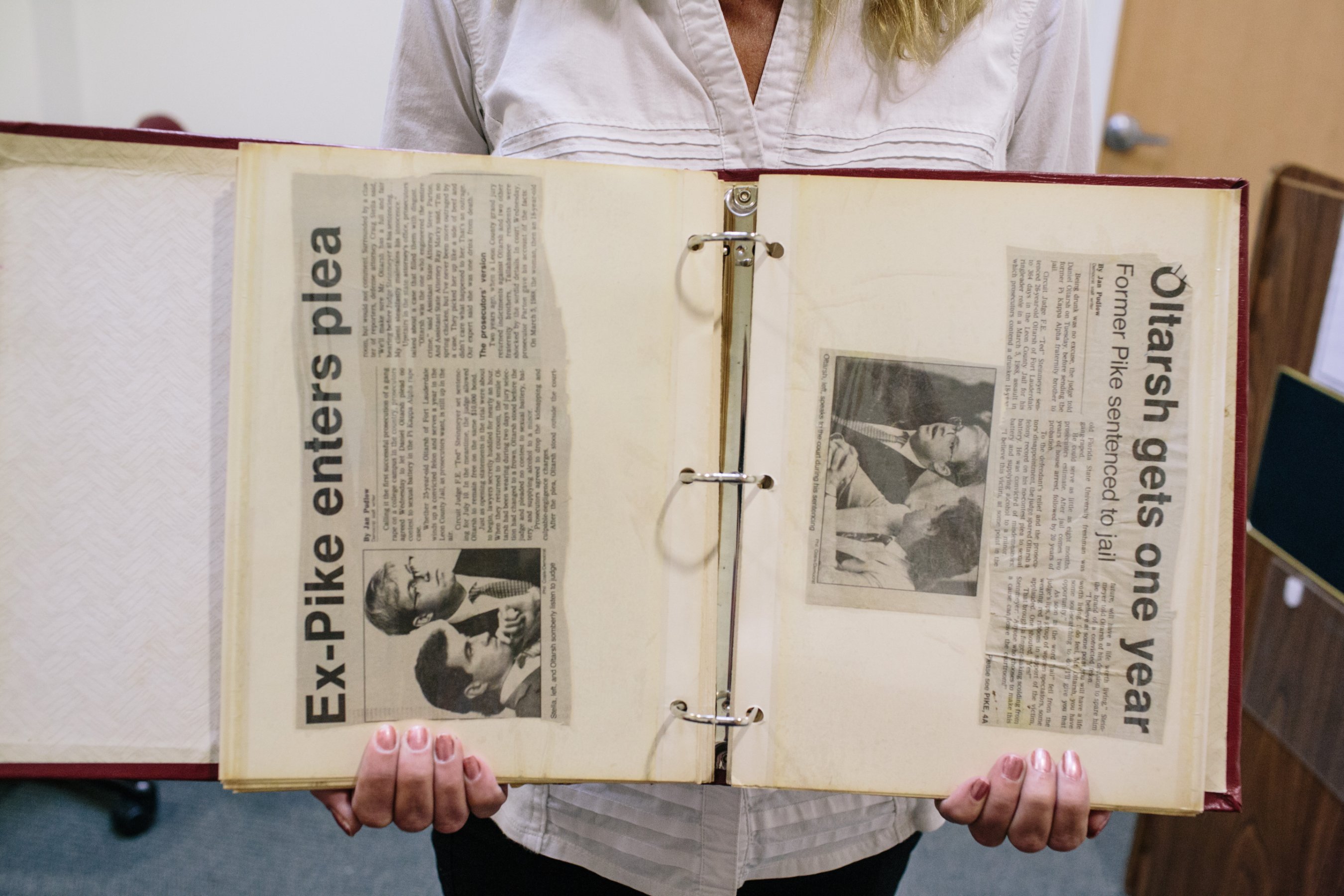

The state built its felony case against Oltarsh, who it determined was the instigator and ring leader. Photographs show the 23-year-old college junior appearing in court wearing jail garb and a smug smile.

As the legal proceedings began, deep divisions surfaced on campus. I was editor of an independent newspaper called the Florida Flambeau that broke the news of Maria’s rape and covered every turn of the story. I understood her need for privacy but was bothered that we never heard her version of events. Letters to the editor attacked Maria as a liar, or someone who deserved what she got. Some called her unpatriotic for smearing the reputations of FSU’s upstanding young men.

Maria couldn’t bear to watch television or read the newspapers. The women in her dorm stopped talking to her. She was afraid to walk out the door.

She couldn’t wait until semester’s end when she could return home to Louisiana to spend the summer with her grandmother. Maria found her hearty laugh as comforting as a good pot roast. Sometimes, her grandmother picked a gardenia from her garden and put it in a glass of water in Maria’s room so she would wake up to the sweet smell. She was the only person in her family to whom Maria confided what had happened.

In the fall of 1988, Maria returned to FSU.

She had a nose job, dyed her hair and exchanged her black clothes for pastels so she wouldn’t be instantly recognizable. She thought she could sit in her classes again as a sophomore. She thought she could reinvent herself.

But when she came across the word “whore” scrawled on her memo board, everything went dark again. She popped over-the-counter sleeping pills, one after another. Luckily, she vomited them before they could kill her.

Her parents arrived from Louisiana, packed up her belongings and took her home. She quit FSU and ended up in a halfway house in Texas, battling post-traumatic stress, depression, alcoholism and eating disorders — typical of many college rape survivors.

The rape set Maria on a downward spiral of shame, self-loathing, fear, anger. And more shame.

In May 1990 Oltarsh’s lawyer, Craig Stella, served her a subpoena to return to Tallahassee for a deposition before a widely publicized trial.

“It was a very hostile environment,” recalls Stella. “I had been practicing law for a while and it was one of the most difficult cases I had to defend. It was war.”

She sat in Room 314-E at the Leon County Courthouse, clutched a cushion to her chest and answered difficult questions. But prosecutors succeeded in persuading the judge to apply Florida’s rape shield law, then fairly new, to her deposition. The judge ruled defense lawyers could not use Maria’s sexual history against her.

Attorney Dean LeBoeuf, who represented Maria throughout her ordeal, says as far as he knows, it was the first time the rape shield law was utilized in pre-trial testimony.

Pi Kappa Alpha brothers in blue blazers packed the courtroom for Oltarsh’s trial. On the other side of the aisle sat a group of women who had decided they would appear there every day to support Maria. They were professors, students and women who worked in rape crisis centers; they wore little red ribbons to show solidarity. Many had written letters to Maria on the eve of her deposition. Patricia Martin, a professor of social work at FSU, was one of them.

“We are here for you,” Martin wrote. “I admire you — only a person with strength and courage could hang in there, like you have done and are doing.”

The women’s letters were Maria’s “lifeline” and became rare treasures from that era. They were the closest thing she received to the kinds of messages of support women and girls can get these days when social media sites like Facebook, Twitter or Snapchat are used for the good.

Maria’s therapist, who spoke to me with Maria’s permission, feels certain that Maria would not have felt as ostracized had her rape happened today.

“We have advanced tremendously in the last 30 years,” says Dr. Tina Goodin. “A lot of what was in the closet then is out today. And social media, when it is used well, changes things a lot. We see a sense of compassion and women asserting themselves.”

What rape survivors want, says Goodin, is to be validated in their experience; to know that what happened to them did not occur because they are crazy. In Maria’s case, the only comfort came from those letters she received from Martin and others.

“I knew she did not have any support,” Martin says. “Her so-called friends were siding with the boys.”

Martin is now retired but remains a researcher on campus rape. She published a widely-cited paper in 1989 on fraternities and sexual assault based on Maria’s case.

“I thought I was aware but I was so shocked by this case,” Martin says. “It was so unsavory — every last bit of it.”

Campus safety had become a hot topic in the 1980s, but Martin says attention to the problem waned in the 1990s. “Maybe we thought things were fixed.”

They aren’t. “Alcohol, fraternities, an adoration for athletes,” she says, “are all important factors.”

In the end, Maria was spared the experience of having to look Oltarsh in the eye. Facing a life prison sentence, he accepted an 11th-hour plea deal.

McPharlin pleaded no contest, had the charges reduced and was placed on probation for a year. Stewart got five years probation on his no-contest plea to sexual battery. Both were spared felony records. Oltarsh received a tougher sentence of 364 days in jail and 20 years of probation.

After his release, Oltarsh violated the terms of his probation by possessing a firearm and failing to tell his probation officer of a change in employment. He was found guilty of sexual battery against Maria and resentenced in August 1992 to eight years in jail. He was released in September 1995.

After his initial sentencing, Oltarsh told reporters that he was convinced he would have been acquitted had all the evidence been laid out in court. He has never spoken publicly about Maria. Nor did he respond to a recent request for an interview made through Stella, his lawyer.

Stella says his client took the plea deal unwillingly; Oltarsh does not believe he did anything wrong.

“I was charged with defending a young man who very much wanted to put this behind him (and not) risk spending 20 years of his life in a penitentiary,” Stella says. “I do believe the facts of the case warranted a not guilty verdict. I thought that then and I believe that now.

“Was it incredibly poor taste?” Stella asks. “Yes, but not necessarily criminal.”

Oltarsh’s probationary period ended this year. He lives in Fort Lauderdale and can be found on the Florida sex offender registry.

‘I felt robbed’

Maria had never seen her deposition until I took her to the Leon County Courthouse to meet with Meggs. I’d caught up with him a few days earlier in his fourth-floor office, surrounded by boxes of files he had pulled for us from a documents warehouse. He told me he liked to reconnect with crime victims in cases he prosecuted.

“I’m proud of you,” he tells Maria. “You didn’t want to go forward but we felt like we had to do this. I think you helped a lot of people in the long run. You were courageous.”

It is only in the last decade, after three failed marriages and the deaths of her mother and sister — both alcohol related — that Maria has begun to heal.

She returned to college in Texas and in 2002 completed a master’s degree in psychology.

“I went back to school because I felt robbed. Robbed of my education, robbed of my typical student life, robbed of my aspirations, robbed of success,” she says. “Those guys took all that away from me. I showed them wrong.”

FSU took the significant step of suspending Pi Kappa Alpha as the investigation unfolded. The fraternity was banned from campus until its reinstatement in 2000. The Pikes own a new house about a mile east of their previous location. Last year, the fraternity was suspended again during another sexual battery investigation but the members were cleared.

Maria knows she will never get an apology — from her attackers or others who revictimized her with their actions.

But she can get off the rollercoaster ride of recovery and relapses that has dominated her life. She has recovered from an anorexic weight of 91 pounds and has not touched alcohol in two years.

“For several years, I blocked it as though it happened to someone else just so I could move forward with my life,” she says. “I was trying to make myself disappear.”

Her words resonate. They are the same words I heard on the other side of the world, when I arrived at a remote village in India to speak with Mathura, a woman who was raped as a teenager by two police officers. They are the same words I use to describe my actions after being raped by a classmate.

At the courthouse, we obtain a copy of Maria’s deposition and other case files. She gasps as she reads her own words all these years later.

She tells me she is proud of 18-year-old Maria’s fortitude.

Rape is ‘not the sum of me’

For years, the old Pike house stood like an eye sore, boarded up and crumbling. For many, it was hard to drive by it without thinking about the rape.

Maria and I stand on the street where the fraternity’s mansion once soared. In its place are new dorms built to match the Old English style of most other buildings on campus and nestled amid trees. It’s an idyllic setting, but Maria sees different images.

They can’t be unseen.

Maria is 46 now and works as a manager in an agency that oversees programs for people with disabilities. She couldn’t have stood again on this corner of the FSU campus any earlier in her life. She was not ready to face the past, she says, until now.

She sees herself in all the young women who walk past us. It’s a different world with smart phones and emergency blue lights every few feet. But in many ways, it feels the same.

“I feel nervous for them,” she says.

She acknowledges that in most of her life, she turned to alcohol to cope with conflict, to numb her pain. And that it has taken all this time for her to shed her shame and say out loud that what happened to her on this street was not her fault. “I didn’t deserve it.”

We both feel drained after our day on campus. It’s a good drained.

“I bear the scars,” she says, “but what happened to me here is not the sum of me.”

I look at Maria, her fingers wrapped around a Marlboro, and feel I have known her for a lifetime. I understand how the women in “The Hunting Ground” were able to connect in such profound ways.

There is solace in shared experiences, I think to myself, even rape. It is as though I don’t have to say my thoughts out loud.

We climb into my Mini Cooper in silence and drive down Jefferson Street, away from campus. Maria, I know, is finally leaving FSU.