The crash of a military blimp in Pennsylvania after it broke free of its mooring on Wednesday has renewed scrutiny of the system’s effectiveness and its cost.

During Wednesday night’s Republican presidential debate, former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee cited the program as an example of misplaced government spending.

“What we had was something the government made — basically a bag of gas — that cut loose, destroyed everything in its path, left thousands of people powerless,” he said. “But they couldn’t get rid of it because we had too much money invested in it, so we had to keep it.”

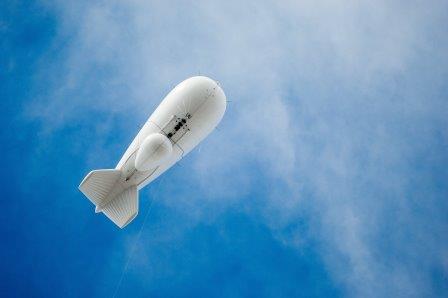

The goal of the system, named JLENS, is to detect and defend against low-flying threats like cruise missiles, battlefield ballistic missiles and aircraft or drones close to the ground.

A stationary blimp called an aerostat, almost the size of a football field, is floated up on a tether to a high altitude from which its radar can scan further over the horizon than ground-based radar in order to more quickly detect potential threats that can then be tracked by another blimp and shot down by defensive weapons like missiles or fighter jets.

But a 2012 report from the Pentagon’s Operational Test and Evaluation office faulted the program for what it called “low system reliability.”

“Testing identified problems with operator controls and displays, non-cooperative target recognition, friendly aircraft identification, and fire control radar software and track stability,” the report said. “These problems require future improvement.”

An L.A. Times investigation last month said the program was slow to roll out, inefficient and expensive, costing $2.7 billion.

“You have a bunch of problems implementing it: hardware problems, software problems and now a bad tether,” said CNN aviation analyst Miles O’Brien. “Makes you wonder if it’s not so much a white helium balloon as it is a great white elephant.”

Another problem for the program: On the day in April when a protester flew a small gyrocopter from Pennsylvania to the lawn of the Capitol without being intercepted, the blimps were not in the air.

Officials at NORAD, the North American Aerospace Defense Command which operates the blimps, said they were having their software upgraded.

Representatives at Raytheon, which makes the radar for the blimps, declined to comment on the program’s status, referring inquiries to NORAD.

Officials at NORAD stressed that the system is one year into a three-year test period, and the agency has not yet determined its effectiveness.

But supporters of the program say it has been steadily improved.

“That system has been excruciatingly tested, successfully, at White Sands, against simulated targets, real targets, and it does the job it was designed to do,” said Chet Nagle, a former pilot now with the Committee on the Present Danger.

“They’ll fix it whatever it is. And the fact that you have a test aircraft crash, or an aerostat break loose, doesn’t invalidate the system,” he said. “The fact of the matter remains, the threat that this system was designed to counter hasn’t gone away.”

The system is intended to address a danger that is difficult to defend against, said military aviation analyst Caitlin Lee: small, low-flying threats near Washington D.C., such as a cruise missile launched off the coast or a small unmanned aerial vehicle. Unlike an ICBM launched from Russia or China, she said, such low-flying objects have a small radar signature and a shorter interval until they arrive near the capital.

“I actually think it’s a pretty interesting system, because it gets at a really hard problem,” she said. “It’s kind of practical for that specific purpose.”

And compared to some of the alternatives, like fighter jets on alert around the clock to intercept incoming threats, a blimp on a tether could be considerably cheaper, she said.