With little effort, anyone can file your official death certificate and throw you into a Kafkaesque, bureaucratic nightmare.

It’s all because we’ve moved our death record system online — and don’t guard it closely enough. It opens the possibility for a new age of high-tech revenge and life insurance fraud.

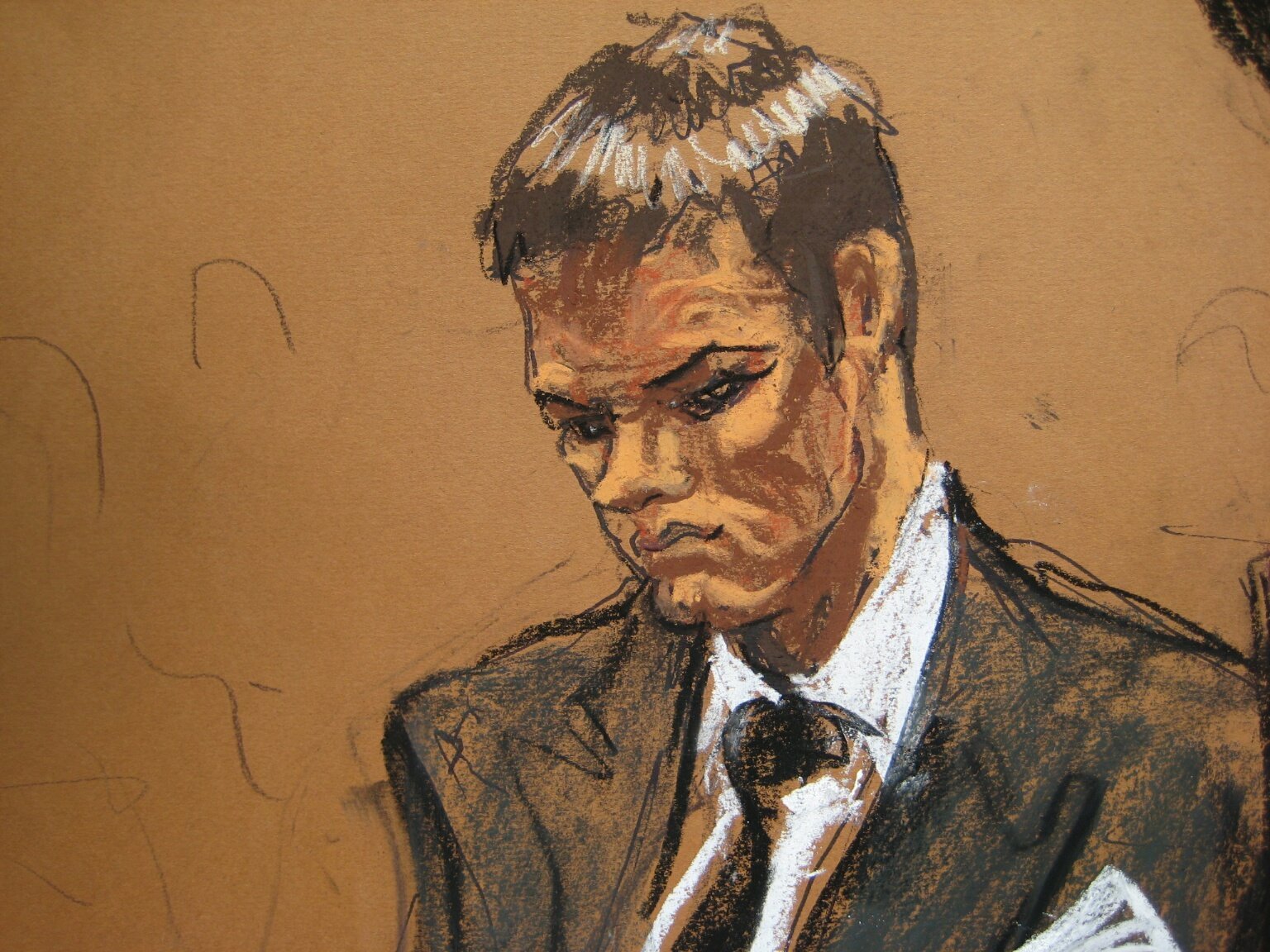

An Australian computer security expert named Chris Rock has discovered how flawed this system is in his home country, the United States and the United Kingdom. And the problem is so widespread, this won’t be fixed anytime soon.

“No one is off limits,” Rock told CNNMoney. “This is a global problem. Anyone with this knowledge can ‘kill’ another person… with the click of a mouse.”

He presented his discovery at the DEF CON hacking conference in Las Vegas last week

Here’s the issue:

Growing populations have forced governments to move birth and death records online. This makes it easier to keep track of fatalities during disasters, such as hurricanes. But it also opens the system up to hacking.

Only doctors and funeral directors can file death records. But it’s frighteningly easy to pose as a doctor or funeral director online. Their names, contact information and professional credentials alone (such as a license number) can be used to start an online account. And all that information is publicly available on government websites.

It doesn’t always work. Some physicians already have a username and password. But most don’t. Few physicians actually file death records, leaving that task to medical examiners instead, Rock said. So, a fraudster can just pick a doctor who hasn’t claimed an online account yet.

An additional problem is that it’s also wickedly simple to register as a funeral director. In Colorado, you don’t need any kind of degree, there’s no exam, and you don’t even need to pay for a license.

“I set up a website, stuck up some pictures of caskets and some flowers. I then applied online to become a funeral director,” Rock said. “Three days later… I was a funeral director. No phone calls. Nothing.”

Filing an actual death record takes a little more homework: You’ll need the person’s contact information and a Social Security number. But those are easily found on hacker forums online.

And yes, there’s a way to profit from this.

Someone could commit fraud by cashing in on life insurance policies. Or, because some modern local probate courts allow for quick, electronic filing of wills, it’s also possible to gain illegitimate access to a “dead” person’s bank accounts.

And the worst part of this? If you’re a victim, you’ll be stuck in a bureaucratic mess of paperwork with governments and credit rating agencies. It already happens to 14,000 people who are accidentally declared dead by the Social Security Administration every year.

Credit bureaus deny you the ability to take out loans. That happened to an 81-year-old grandmother in New Jersey.

Bank accounts close, checks bounce and fees rack up. That happened to a mother in Virginia.

Health insurance policies get canceled. The IRS rejects tax returns and stops sending refunds. These happened to a woman in Tennessee.

“The law isn’t written for the dead returning,” Rock said.