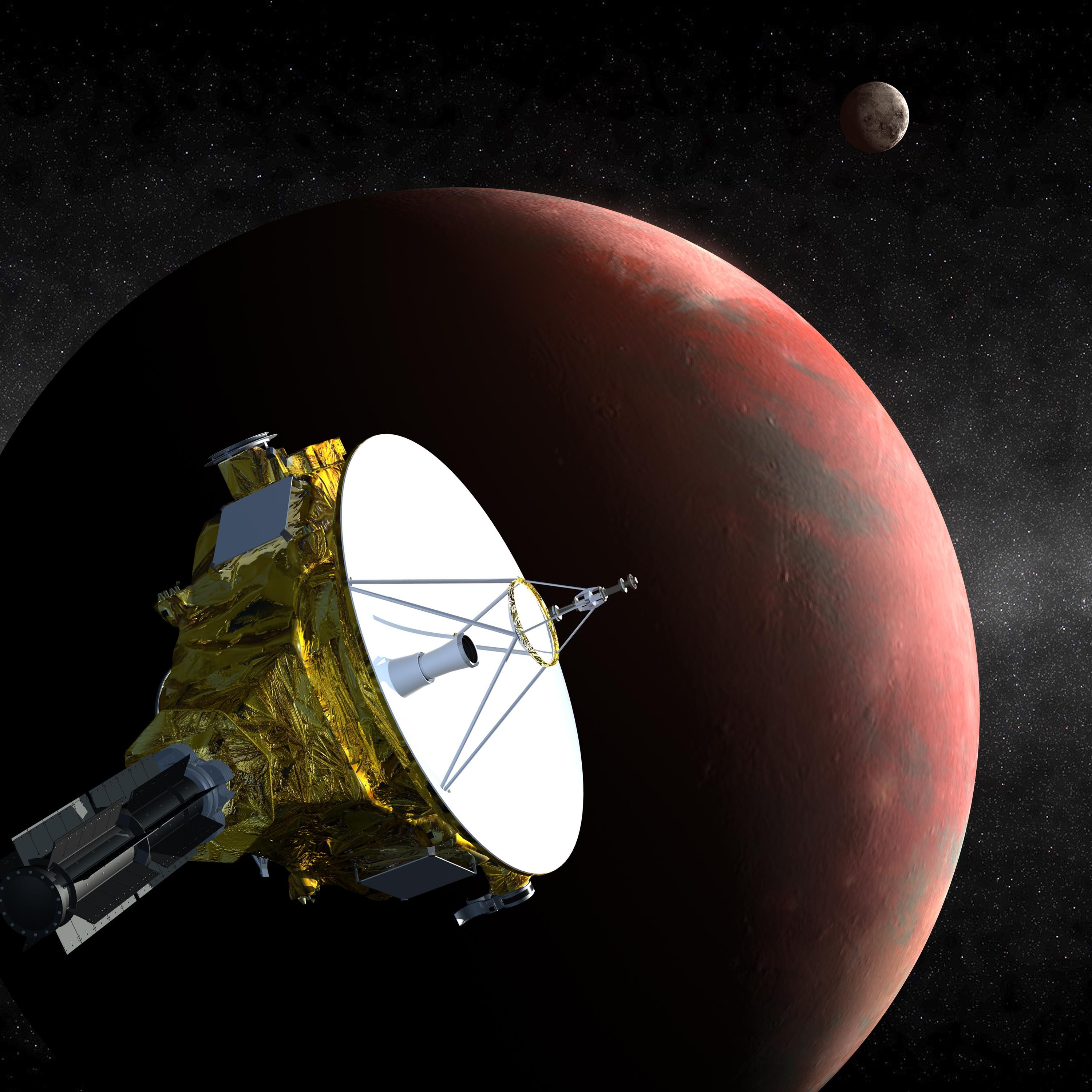

It’s traveled more than nine years to get there and it will only stay a few hours, but a small space probe already is revolutionizing the way we look at Pluto.

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will be within 6,200 miles (9,978 kilometers) of Pluto’s surface at 7:49 a.m. ET on July 14 — Tuesday — becoming the first spacecraft to do a flyby of the icy world.

It also will pass about 17,000 miles from Pluto’s largest moon, Charon.

“The data is going to start raining down from the sky,” Alan Stern, the mission’s principal investigator told CNN Saturday in a phone interview.

The probe already is beaming back the best photos ever of Pluto and Charon.

“Pluto and Charon are both mindblowing,” Stern said. “I think that the biggest surprise is the complexity we’re seeing in both objects.”

New Horizons will be traveling about 31,000 miles per hour (14 kilometers per second) during the main encounter, which will last about eight to 10 hours, NASA says.

The mission will complete what NASA calls the reconnaissance of the classical solar system, and it makes the U.S. the first nation to send a space probe to every planet from Mercury to Pluto. The probe has traveled more than 3 billion miles to reach Pluto.

The probe gave scientists a scare on July 4 when they lost contact with it after a computer glitch at mission control at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

“We did hit a speed bump,” Stern said at a briefing on July 6. Some science data was lost, including images, he said.

Stern said on Saturday the probe is working fine.

“The spacecraft is performing flawlessly, so is the instrument suite and we are on schedule for arrival.”

What will you see during the flyby? NASA says on its website there will be a few images before New Horizons flies through the Pluto system and a few more after the encounter. The images from the close encounter will be released on July 15 at 3 p.m. ET.

Why go to Pluto?

New Horizon’s core science mission is to map the surfaces of Pluto and Charon, to study Pluto’s atmosphere and to take temperature readings.

The spacecraft was launched on January 19, 2006, before the big debate started over Pluto’s status as a planet. In August of that same year, the International Astronomical Union reclassified Pluto as a dwarf planet.

But Stern disagrees with the IAU’s decision.

“We’re just learning that a lot of planets are small planets, and we didn’t know that before,” Stern said in a NASA news release. “Fact is, in planetary science, objects such as Pluto and the other dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt are considered planets and called planets in everyday discourse in scientific meetings.”

New Horizons has seven instruments on board to help scientists better understand how Pluto and its moons fit in with the rest of the planets in our solar system.

The planets closest to our sun — Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars — are rocky. Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are gas giants. But Pluto is different: Even though it is out beyond the gas giants, it has a solid, icy surface.

Pluto also is small, about the size of the United States, Stern said. Its largest moon, Charon, is about the size of Texas. Pluto also has four smaller moons: Nix, Hydra, Kerberos and Styx.

Even before its closest encounter with Pluto, New Horizons was giving scientists new details about the planet: Images taken during the approach showed a series a black spots near Pluto’s equator, each hundreds of miles across.

Beyond Pluto

New Horizons looks like a gold foil-covered grand piano. It’s is 27 inches (0.7 meters) tall, 83 inches (2.1 meters) long and 108 inches (2.7 meters) wide. It weighed 1,054 pounds (478 kilograms) at launch.

The probe won’t orbit Pluto and it won’t land. Instead, it will keep flying, heading deeper into the Kuiper Belt, a region that scientists think is filled with hundreds of small, icy objects.

“The universe has a lot more variety than we thought about, and that’s wonderful,” Stern said. “The most exciting discoveries will likely be the ones we don’t anticipate.”