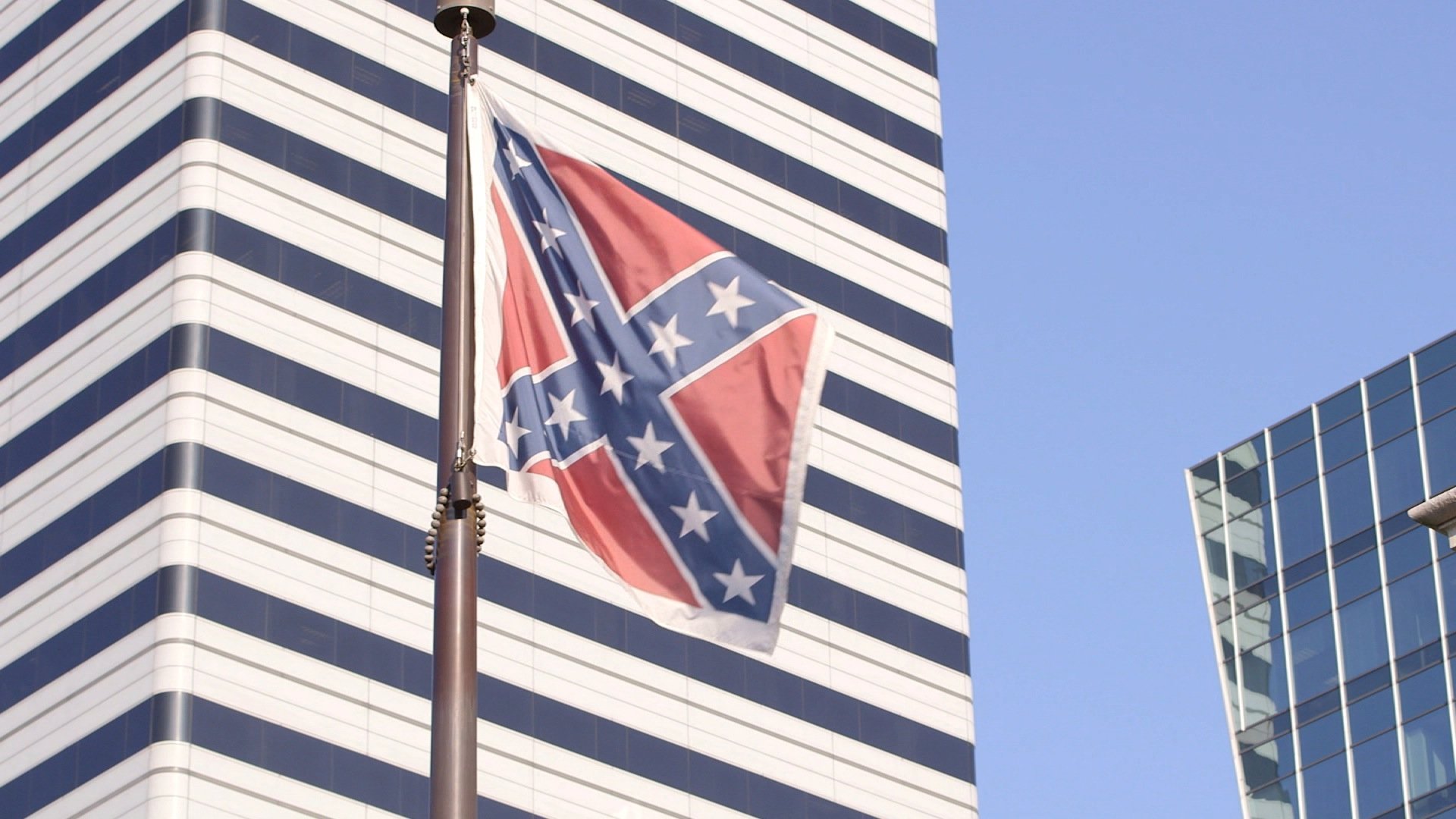

Even if the Confederate battle flag comes down, there’s still a lot to see at South Carolina’s state Capitol.

An 8-foot-tall bronze statue of Ben Tillman standing on a granite pedestal praises his “life of service and achievement” as governor and U.S. senator at the turn of the 20th century, but makes no mention of the lynching parties he infamously hosted.

Not far from that is a life-size bust of J. Marion Sims, the 19th-century physician whose advancements in gynecology came via experimental surgeries on enslaved women.

There are homages to Confederate cavalry leader Wade Hampton III, diehard slavery advocates John C. Calhoun, George McDuffie and Robert Hayne. James F. Byrnes and Strom Thurmond, more modern figures in South Carolina politics, are honored, too. At a time when segregation was challenged, they were among its fiercest defenders.

Though there is a monument to African-Americans as a group, no individual of color is honored on the Capitol grounds — except for a mention on Thurmond’s monument of his biracial daughter Essie Mae Washington-Williams, whose identity was kept secret until six months after he died.

Wednesday, one week after the shooting deaths of nine black worshipers — including a state senator — in a Charleston church, lawmakers in Columbia are debating whether it is time to take down the flag. Dylann Roof, a 21-year-old white South Carolinian man, told police he shot the churchgoers because he wanted to start a race war.

Still, regardless of the outcome of the lawmakers’ debate, the flag is only one item in one place in one state.

Countless roads, parks, schools and monuments across the country are named after Confederate leaders and segregationists, and the flag flies in several other states, in front of courthouses and government buildings. The Confederate battle flag and national flag are incorporated in the state flags of, respectively, Mississippi and Georgia.

“There are thousands — I’m not sure it’s possible to know how many — places in America that honor the Confederacy,” said Maureen Costello of the hate-group-monitoring Southern Poverty Law Center. “When we name these places — or we don’t change the names of places that have been around for years — we allow white America to send a message to black America: ‘Not only do we deny your experience, but we’re going to celebrate the people who celebrated your oppression.'”

Memorials a reflection of their own time

Over the past decade, there has seemed to be a cultural push to re-examine why these places named after leaders who fought to the death to defend slavery still exist in a country that professes to have made great strides in race relations.

“In some ways, it depends on when these places and monuments were built,” said Kenneth Janken, the director of the Center for the Study of the American South at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

He said there are a few significant periods through history that have seen a huge push to erect Confederate memorials or name places after its leaders. The first happened after the Civil War, when the South’s losses were fresh. Another happened in the 1950s and 1960s as a reaction to the civil rights movement, he said.

What’s happening now in South Carolina might be another spike in that timeline, he said.

“Each generation writes its own history. It’s a struggle,” he said. “The fact that there’s a flag flying over the statehouse or within view of the statehouse … we must remember that they were put there because one side had the power to do it.”

In Georgia, a state flag featuring the Confederate battle flag was instituted in 1956. In 2003, Gov. Roy Barnes exercised his executive authority — despite fierce opposition — to change the flag. It’s widely believed that he paid for that move in the next election as Sonny Perdue took office. Perdue said he would reinstitute the battle flag, and while that did not happen, the flag has flown elsewhere in the state.

The current Georgia flag is identical to the Confederate national flag, except that it incorporates the Georgia state seal.

In April, a local chapter of Sons of the Confederacy reportedly raised the battle flag over the county courthouse in Summerville, Georgia, with the county’s approval. The move angered some, including the town’s first African-American mayor.

The database of the National Center for Education Statistics shows at least 20 schools named for Robert E. Lee in the United States. Nine are named after the Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson.

Communities have fought for years over whether some of the places should be renamed. In Memphis, lawsuits were filed over attempts to rename three parks that had been named after Confederate leaders, including Nathan Bedford Forrest, the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

Recently in Texas a petition has circulated to remove a statue of Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, from the University of Texas-Austin campus.

Not just Southern, not just white

Not all representations of Confederate icons are used in veneration. Some have tried to reappropriate the flag in an attempt to remove its historical sting, much in the same way that some use the n-word colloquially.

Some opinions, and the people who hold them, simply defy the script.

CNN iReporter Byron Thomas, a black 23-year-old student at the University of South Carolina, said he researched the flag, prompted by curiosity about an ancestor who he believes fought for the Confederacy.

“I’m not going to turn my back to what he did for the South,” he said. He hangs the flag in a window in his apartment.

“I love to show [it] when people walk in my room,” he said. “I have the American flag, South Carolina flag and the Confederate flag. I have no shame in the flags that I support.”

WBEZ journalist Logan Jaffe compiled ironic examples, including Kanye West’s wearing of the flag, a painter portraying it in his work, and Karen Cooper, a black woman in Richmond, Virginia, who likes to wave the flag because to her, it simply represents Southern pride.

If Cooper wants to buy a Confederate flag license plate in her state, her time might be running out. This week Gov. Terry McAuliffe announced he was pushing to ban it.

Maybe she can go to Texas to buy a miniature flag in the state Capitol gift shop. Or if that doesn’t work, travel north for more Confederate emblems.

A monument to the Confederacy went up in 2007 in Georgetown, Delaware.

There’s a statue honoring the Confederate States of America in Baltimore, the city gripped with riots in April over the death of black man Freddie Gray while he was in police custody.

That brings full circle to something that has been bothering UNC’s Janken. Taking down the Confederate flag in South Carolina is important, he agrees, but he keeps thinking about Michael Brown, the unarmed black teen killed by a white officer in Ferguson, Missouri; Tamir Rice, the unarmed black 12-year-old killed by a white officer in Cleveland; Trayvon Martin, the unarmed black teen killed by neighborhood watch coordinator George Zimmerman in Florida; Eric Garner, the unarmed black man who died after a struggle with police in New York.

Six officers have been indicted on charges ranging from illegal arrest, misconduct, assault and involuntary manslaughter in Gray’s death.

“But why do we keep coming back to these symbols?” Janken asked. “In some ways it’s a distraction. People are being killed. You can take down a symbol, but that doesn’t mean you can’t address the larger problems those symbols represent.”

Something different in the air in S.C.

South Carolinian Tom Hall has given a lot of thought to what all these monuments and statues and the flag mean.

An attorney born on a farm in Chester, he has spent the past four years filming a documentary that asks, why do people in South Carolina fly the Confederate flag?

“I have never understood why do we keep it up there, flying at the Capitol, when it hurts every black person’s feelings? Why are we so invested in that flag?” the 47-year-old said. “I can tell you that nowhere in the history books when I was growing up was that explained in any truthful way.”

The film, “Compromised,” offers a rich and storied telling of the state’s investment in slavery, and how racist attitudes and customs have morphed with each generation in accordance with the mores and politics of the day.

He interviewed dozens of people, including several people who were around in 1961 when the flag went up, they said, as an act of defiance on the part of a few lawmakers against the federal government’s push for integration and civil rights.

Hall plans to give all money raised during his film’s premiere this Saturday at Columbia’s Nickelodeon theater to Charleston’s African Methodist Episcopal Church, the site of the June 17 massacre.

He knew state Sen. Clementa Pinckney, the church’s senior pastor and one of the victims. “He was a gentle, wonderful person with a very strong moral conscience,” Hall said, his voice rising with emotion.

The swelling movement among lawmakers and local leaders to remove the flag from the Capitol grounds is more than politics, he said. “I’m proud of the Republican party for stepping up, and I do believe they have. They’ve done what I never expected.” he said. “Some of these lawmakers — it’s about Pinkney. They loved that man.”

But it feels like there’s something different in the air in South Carolina, too, he said.

He could feel it at the rallies he’s spoken at and attended in which leaders and regular people of different races, ages and experiences are coming together. He hopes the moment lasts long enough to have some real talk about race. He hopes it stretches past any ceremonies to take down a flag.

“If you take your 12-year-old to the Capitol and read the plaques on the statues, you’d think, ‘Wow, what a bunch of nice white men!’ It’s almost like their mamas wrote those descriptions,” he said.

“What we need to do is keep these monuments,” Hall insisted. “Keep them up to remind us all. But add to them, tell the truth about who and what they are about. Tell the full truth of our history.”