The U.S. Army said last week it will begin awarding Purple Hearts to those killed or wounded in the 2009 shooting at Fort Hood, Texas.

And Secretary of the Army John McHugh announced Thursday that he’s directed the Army to provide benefits to victims of the 2009 attack on Ft. Hood.

There had been some question as to whether they could receive such benefits, based on a need for Congress to act.

McHugh announced the decision to award Purple Hearts to Fort Hood’s victims in a statement last week, calling the honor “an appropriate recognition of their service and sacrifice.”

The Army will also award the civilian equivalent of the Purple Heart, the Defense of Freedom Medal, to non-military victims.

“The Purple Heart’s strict eligibility criteria had prevented us from awarding it to victims of the horrific attack at Fort Hood,” McHugh said, but noted that recent legislation has allowed them to move forward in recognizing the victims.

The decision was made possible by an amendment to the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), sponsored by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), which expanded eligibility for the Purple Heart to include troops killed in an attack where “the individual or entity was in communication with the foreign terrorist organization before the attack,” and where “the attack was inspired or motivated by the foreign terrorist organization.”

“It’s long past time to call the Fort Hood attack what it was: radical Islamic terrorism,” Cruz said in a statement in December, after the NDAA was passed. “And, this recognition for Fort Hood terrorist victims is overdue. The victims and their families deserve our prayers and support, and this legislation rightly honors them for defending our nation in the face of a heinous act of terror.”

The Purple Heart is a combat decoration and was previously only awarded to service members who had been injured or killed in action.

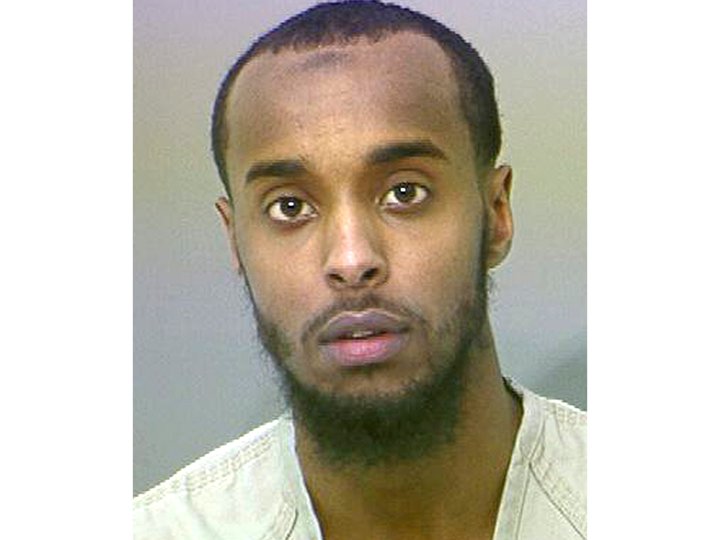

On Nov. 5, 2009, Army psychiatrist Maj. Nidal Hasan opened fire at Fort Hood, killing 13 and injuring more than 30.

Hasan claimed to have targeted soldiers who would be deploying to Afghanistan, or who had recently returned. Authorities say he committed the attack so he would not have to go to overseas to fight against Muslims.

Prior to the attack, Hasan had exchanged emails with radical cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, an American-born spokesman for al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula who was later killed in a U.S. drone strike.

More recently, he sent a letter to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi asking to become a citizen of the group’s self-proclaimed Islamic caliphate.

A military jury convicted Hasan in 2013 and recommended the death penalty. The mandatory appeals process is expected to last for several years.