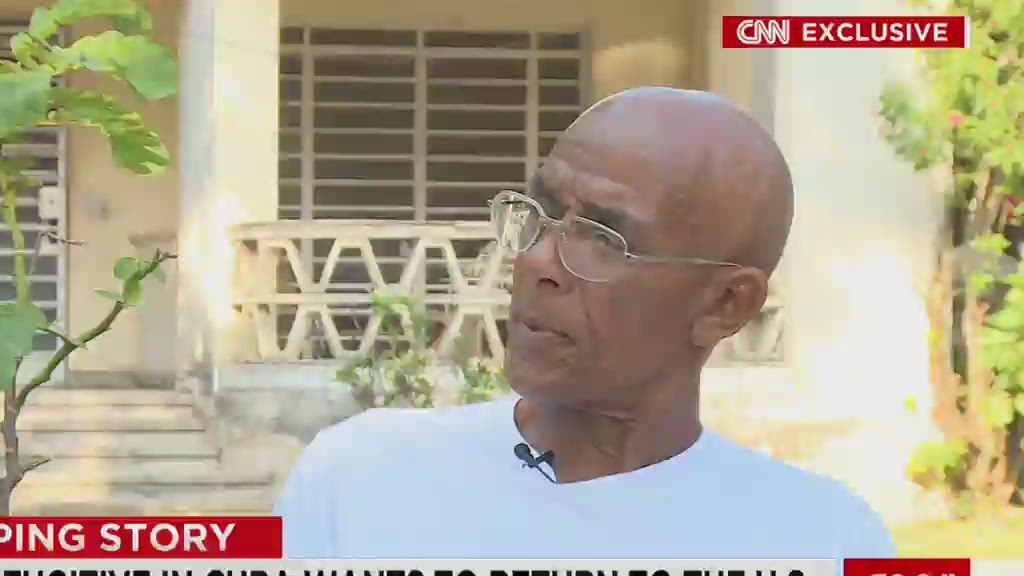

Charlie Hill sits in a dark bar on a blindingly sunny Havana day.

“Hey man,” he says with a smoker’s rasp and a nod that indicates he knows you have been looking for him. But then a lot of people have been looking for Charlie Hill for a long time.

For 43 years Cuba has provided refuge for Hill from facing charges that he killed a New Mexico police officer and hijacked an airliner to Havana.

Hill, now 65, decided to give CNN an interview after we’d spent two years trying to reach him. He wants to discuss how for the first time he is considering leaving his safe haven and returning to the United States.

Before talking more, Hill finishes his plastic glass of beer and takes a final draw on his stub of a cigarette. We step out into the sunlight and go to a park where Hill starts to give his reasons why he may soon end his long run from the law.

“I miss my country,” he said, his voice cracking. “I miss my family. I would like to go back and see where my grandparents were born, where I was born, where I went to junior high. Eat some blackberry pie. Even go to McDonald’s. That’s only natural.”

Hill was a black power militant and said he is still a revolutionary. But he craves the kind of French fries that only capitalism can make.

After five decades of Cold War-era mistrust, the United States and Cuba are working to re-establish full diplomatic ties, but cases like Hill’s present an obstacle to an improved relationship.

New Mexico, where Hill’s case has been open for decades, followed up on the shift in policy from the Obama administration with Gov. Susana Martinez asking Washington to pursue Hill’s extradition.

Critics of the new opening to Cuba say Havana’s harboring of fugitives like Charlie Hill is enough of a reason to maintain a hard line against the government of Raul Castro and keep Cuba on the State Department list of countries that support terrorism.

Hill, now 65, may extradite himself first, saying the warming of relations between the United States and Cuba could mean an end to what he calls his “exile” on the communist-run, Caribbean island, even if his return brings jail time.

New Mexico Police Chief Pete Kassetas said he welcomed the news of Hill’s possible surrender. “I understand that the social environment was very different in 1971 than it is today. I encourage him to return to face the charges against him on the state level and on the federal level and end his self-imposed exile in Cuba.”

Charlie Hill’s journey began on November 8, 1971, when he and two other men — Michael Finney and Ralph Goodwin — were pulled over on I-40 outside Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the middle of a cross-country drive.

All three men were members of the Republic of New Afrika, a black power militant group that sought to break off Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina into a separate nation for African-Americans.

They were on the way from California to the South with a car loaded with weapons to support the cause.

New Mexico State Police Officer Robert Rosenbloom pulled over their rented Ford Galaxie sedan, on suspicion that the car was stolen, said Kassetas.

At 10:41 p.m., Rosenbloom called in the California license plate of the militants’ car, according to the New Mexico Law Enforcement Memorial. Fourteen minutes later the dispatcher radioed Rosenbloom back but was unable to reach him.

A police officer arriving at the scene found Rosenbloom’s body lying face down on the road, Kassetas said.

There was a single bullet wound to his throat. Rosenbloom gripped his flashlight with one hand and his gun with the other, according to the records of the New Mexico Law Enforcement Memorial.

The sedan was found the next day abandoned with three military rifles, a 12-gauge shotgun, “revolutionary literature,” bomb-making materials and hundreds of rounds of ammunition

Hill copped to riding in the sedan that Rosenbloom pulled over but refused to say who shot the policeman.

“I am not a cop killer. I am a freedom fighter,” Hill said. “I am a Vietnam vet and people never ask me if I killed Vietnamese because that was authorized by the American government. I dedicated myself to liberating my people.”

For 19 days, Hill said, the men hid out in the New Mexico desert, working on an escape plan as 250 law enforcement officers closed in.

“We had to go into exile so we hijacked a plane,” Hill said.

The three men, Kassetas said, commandeered a tow truck at gunpoint, crashed through a fence onto the runway of Albuquerque International Airport and ran up the gangway to TWA Flight 106.

Elizabeth Walthall was a flight attendant aboard the Boeing 727 when the fugitives stormed aboard.

“They were dirty and stunk from hiding out in the hills,” she told CNN from her home in North Carolina.

Walthall, now 72, said Charlie Hill put a blade to her throat.

“He told me to do what he said because ‘this is no butter knife.’ I told him, ‘Well, I am no piece of bread.'”

Hill laughed, she said, and lowered the knife.

Hijacker Michael Finney glowered and pointed a pistol at the flight attendants, Walthall said, a tremor of fear audible in her voice, as if the hijacking had just happened.

“Finney said he would shoot us and that he had already killed a man,” Walthall said.

The hijackers ordered the crew to fly to Africa. Informed the plane couldn’t fly that far, they changed their destination.

Take us to Cuba, they told the pilot.

The trio knew Cuba would most likely let them stay.

After seizing power in 1959, Fidel Castro blasted Washington for failing to send back the Batista regime officials who streamed to Miami to escape Castro’s revolutionary tribunals, effectively ending the extradition agreement between the two countries.

A rash of airplane hijackings to the island soon followed.

Cuba became popular with leftist revolutionaries as well as common criminals seeking a country beyond the reach of U.S. law enforcement.

“If anything went down, you went to Cuba,” Hill said.

En route to Havana, flight attendant Walthall said she served the men bottles of Michelob beer. When they finished, she saved the bottles in airsickness bags so U.S. law enforcement later would have their fingerprints.

After landing, Walthall said she last saw Charlie Hill and the other hijackers as Cuban soldiers escorted them off the plane.

Years later, the flight attendant said she experienced flashbacks of the hijacking and sometimes prayed for Hill.

“I think he is a lost soul,” she said.

Revolutionary Cuba soon disappointed Hill. Cuban officials denied his request for military training to fight with revolutionary groups in Africa.

Instead he was put to work cutting sugar cane, doing construction and administrating a clothing store.

One of the many menial jobs he worked, he said, put him under the supervision of Ramón Castro, Fidel Castro’s older brother.

“He has a big beard and looks just like Fidel,” Hill remembered. “He was good to us, made sure we were always well fed.”

In 1996, then-New Mexico Rep. Bill Richardson traveled to Cuba to discuss Hill’s extradition with Fidel Castro.

“I talked to Fidel and he said, ‘No way, under no circumstances would he turn them over, that they were legitimate fugitives,” Richardson told CNN. “I got a very strong signal not only would I not be allowed to bring back Charlie Hill but I wouldn’t even be allowed to talk to him.”

Hill is now the last living member of the trio of hijackers. U.S. officials said that Ralph Goodwin drowned in 1973 and Michael Finney succumbed to throat cancer in 2005.

Married and divorced twice in Cuba, Hill has two children on the island and he worries about leaving them if he were to return to the United States.

But Hill said he wants to visit his daughter, who was 6 years old when he left, and who he hasn’t seen since. He dreams of meeting the five grandchildren he has in United States. He’s gone as far as hiring a New Mexico attorney, in case he decides to negotiate a surrender.

His Cuban government pension is a meager $10 a month, he said. Not nearly enough to support him or even buy toys for his 8-year-old Cuban son.

Hill said he became a babalao, or Santeria priest, but still hasn’t found peace. He admitted he smokes too many unfiltered Cuban cigarettes and drinks too much cheap rum.

And there’s always the possibility that the Cuban government has held onto Hill and other U.S. fugitives, simply waiting for the right moment to trade them to the United States.

He said he is fine with that fate.

“They took me in,” he said. “If the Cuban government feels me going is for the benefit of 12 million people, that’s my sacrifice. I don’t worry about that.”

As the interview ends, Hill lights another cigarette. A group of Americans touring Havana in a 1950’s classic car pull up to the park. They have no idea they are feet away from a wanted fugitive, but as Hill would say, that’s Cuba.

Hill isn’t interested in staying in touch. He doesn’t have a cell phone. Too poor, he says. He won’t say exactly where he lives in Havana. He has to be cautious.

And as he walks off, once again, he is gone.