The desks of the small Madrassa are empty. Its 573 students, all male, are staying home after Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta announced three days of national mourning following last week’s deadly attack at a nearby university.

Only a few kilometers away, 147 people — mostly students — were brutally massacred when Al-Shabaab militants invaded the campus in Garissa, a town in northeastern Kenya.

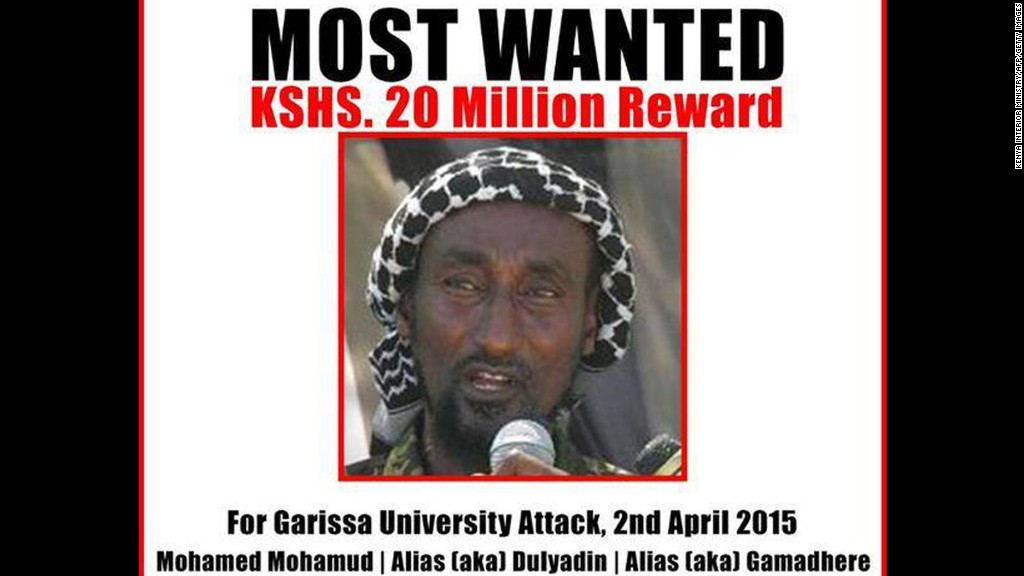

We’ve come to this particular Islamic religious school because the man suspected by Kenyan authorities of being the “mastermind” behind the atrocity — Mohamed Mohamud — once taught here.

“He was someone who was very quiet, he didn’t like too much talk,” recalls Sheikh Khalif Abdi Hussein, the Principal at the Madrassa. He says he also taught with Mohamud for two years.

“When he left the Madrassa, he joined Al-Shabaab. But before, he was normal, just like me and other people.”

What worries authorities here is exactly that — Mohamud was Kenyan.

Kenya a target

But now, say officials, Mohamud is in command of an Al-Shabaab militia based near Kenya’s long, porous border with Somalia — about 118 miles (190km) from Garissa — who are believed to be responsible for numerous cross-border attacks into Kenya.

The Islamist militant group, who are allied with al Qaeda, have been waging a bloody campaign for control of Somalia. With Kenyan troops part of an African Union force deployed in support of Somalia’s United Nations-supported government, Kenya has now become a target.

Last year, an attack by Al-Shabaab on a shopping center in the country’s capital, Nairobi, claimed the lives of 68 people.

Now Mohamud stands accused of being behind Thursday’s attack — the deadliest attack in the nation since al Qaeda killed more than 200 people at the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi in 1998.

Disaffected youth

But Mohamud is not Kenya’s only homegrown terrorist.

The Kenyan Interior Ministry has said at least one of the four gunmen who carried out the attack on the university was also Kenyan. Abdirahim Abdullahi was in his 20s and the son of a government chief. His father says he lost contact with his son in 2013, shortly after he left university. The Kenyan government is concerned that Al-Shabaab is recruiting disaffected youth from inside the country.

“Our task of countering terrorism has been made all the more difficult by the fact that the planners and financiers of this brutality are deeply embedded in our communities,” President Kenyatta said during an address to the nation in the aftermath of the massacre.

Meanwhile, Sheikh Khalif insists his Madrassa has nothing to do with Mohamud’s extreme, violent ideas.

“This man is a dangerous man, a killer, a criminal,” he says.

But he was also once a neighbor. And so Kenyans must now look within to tackle this very real threat to the country’s — and the region’s — stability.