Change has come to Ferguson.

After months of turmoil and upheaval, months of frustration and anger, the beleaguered city has a new governing board. And it looks very different than the old one.

Buoyed by a higher-than-normal 30% turnout, two African-American candidates won their wards Tuesday night to make the six-member City Council 50% black. Ferguson’s population of about 21,000 is 70% black, but the City Council was predominantly white, as is the police force.

Supporters of both candidates said that from the tragedy of a young black man’s death, a new day dawned in Ferguson.

Ella Jones screamed when her victory became official late Tuesday night. She won 49.76% of the vote.

“Thank you, Ward 1. I love you,” an emotional Jones said at a party held at Drake’s restaurant.

She will become the first black woman ever to sit on the Ferguson council.

But both Jones and Wesley Bell, who won the Ward 3 seat with nearly 67% of the vote, said they did not see their victories from a racial perspective.

Jones, who resigned her job as a Mary Kay cosmetics sales director to run for office, said in her ward, she heard the same complaints from a 65-year-old black man as she did from his white peers.

“My job is to be that catalyst so we can put a new face on Ferguson,” she said.

Bell, a lawyer and criminal justice professor, said, “I’m more interested in having quality on the council,” when asked about the change in its racial makeup.

He had made community policing his No. 1 priority and said he intends to be deeply involved with the hiring of a new police chief in this St. Louis suburb. The former chief, Tommy Jackson, resigned after a scathing U.S. Department of Justice report found systemic discrimination against African-Americans in law enforcement and the municipal court.

Bell said he wants Ferguson’s police officers to be judged by the number of people they know in the community, not by the number of tickets they issue.

One other seat was up for grabs in Ferguson. That was won by Brian Fletcher, a former mayor who launched the “I Love Ferguson” campaign to raise money for mom-and-pop businesses that were hurt by the violence and vandalism during the protests last fall. Fletcher beat his opponent, Bob Hudgins, with 56.7% of the vote.

Fletcher told voters he was best suited for a City Council job despite his critics’ claims that he was too entrenched in the old guard.

“I understand that feeling, but those individuals don’t know me,” he said.

Fletcher said he had contacts with elected officials from his almost three decades in politics. That would be an invaluable asset in getting Ferguson back on its feet, he said.

The city is required to approve a new budget by the end of June, and the new council will have to look for alternative sources of revenue to replace the $3 million or so lost from money generated by traffic tickets and fines.

“That amount will drop significantly,” Fletcher said.

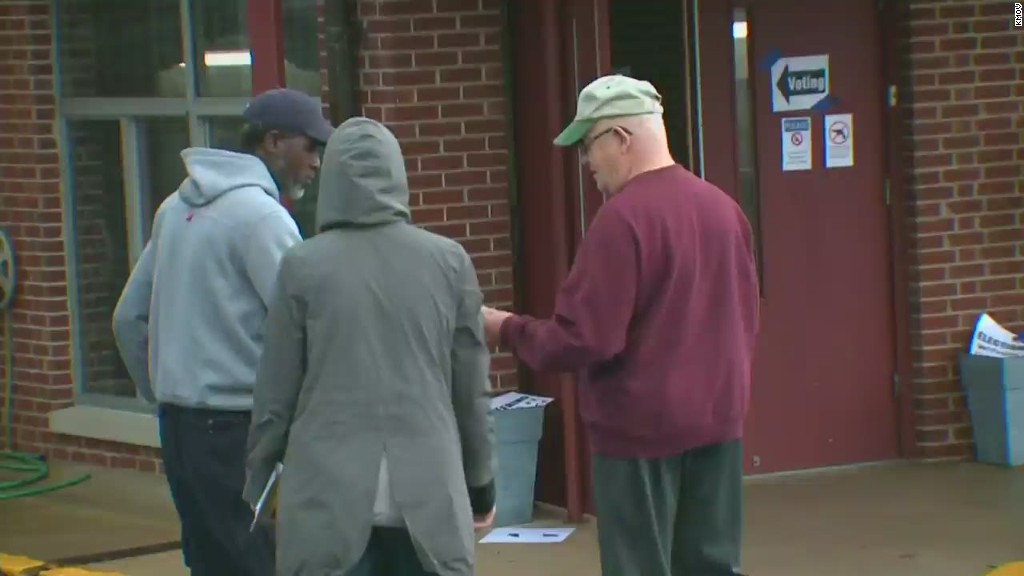

Earlier in the day, the skies grew dark and the radio crackled with warnings of flash floods. Amid the rain, Ferguson opened its polls at 6 in the morning with concern that few would come out to vote in such a pivotal election.

But Tuesday was different.

It was the first city election since white police Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed unarmed black teenager Michael Brown in August.

There was dread, especially in the African-American community, that if the turnout was low, then all the protests, investigations and calls for change would have been in vain. The candidates who had run campaigns calling for change hoped a decent turnout would weigh in their favor.

“That is what our democracy about,” Bell said.

Bell ran against Lee Smith, a retired electrical plant employee, in Ward 3, which includes Canfield Drive, where Brown was killed, and the West Florissant Avenue business corridor that felt the brunt of the protests and the vandalism. Charred, heavily damaged buildings still stand as scars of Ferguson’s despair and anger.

“You got your vote on?” yelled Tommy Chatman Bey, a Bell supporter who was distributing campaign literature at Koch Elementary School, the precinct closest to where Brown lived.

Some residents did have their vote on. They felt a duty to vote this year. One of them was Yvette Bailey, 41, who works as a planner for Coca-Cola. Yes, she voted in presidential elections, but she never paid much mind to local races. Until now. Even though she was aware of the problems around her, Brown’s killing, she said, woke her up.

“It made me think of all the males in my family,” said Bailey, who lives right off Canfield Drive.

She was undecided about who to vote for until the last minute when she walked into the polling station with another voter and they discussed the race.

Bailey decided to cast her vote for Bell simply because he was a young man. She thought he had energy and was more in sync with Ferguson’s youth.

“I think he will be more open-minded,” she said after voting.

Changing the way Ferguson polices its people was No. 1 on many a voter’s agenda. Even the candidates who take issue with the Department of Justice report on Ferguson agreed that the city needed change when it came to policing.

“We have to get out of this law enforcement for business,” said candidate Doyle McClellan, coordinator of the computer network security program at Lewis and Clark Community College.

McClellan referred to the DOJ’s finding that Ferguson issued fines and traffic tickets to generate revenue for the city.

“That’s not a good thing,” McClellan said as he stood in the drizzle at a polling station, hoping to persuade voters who were still undecided.

Ted Heidemann, a 67-year-old retired airline pilot, said he voted for Fletcher.

If some residents saw Fletcher as part of the problem, Heidemann asked why no one complained when Fletcher was mayor. He said Brown’s shooting brought a lot of bad things to light.

“We didn’t realize the effect some of the institutional problems had on poor people,” he said. “Some things need to be changed, and we are aware of that.”

By midafternoon, Fletcher said the numbers were looking good. At a church where voters from all three wards were casting ballots, Fletcher predicted a 40%-50% turnout.

When the rain let up for a few minutes, a stream of voters trickled into the First Presbyterian Church in downtown Ferguson to cast their votes.

Ellory and Kathy Glenn both voted for Fletcher’s opponent, Hudgins, a political novice who attracted attention as a white man who routinely stood with protesters on the front lines. Hudgins likes to talk about how he married a black woman and has a biracial teenage son.

“I wanted change,” said Ellory Glenn, 60, who is black. His wife is white. He said the couple moved to Ferguson after he retired from the Marine Corps in 1995 because they felt it was a racially welcoming place.

But now, after all the problems rose to the surface, it’s time for fresh blood on the council, Glenn said.

“Quit using law enforcement as a revenue stream,” Glenn said. “That’s like using the military to go into places and looting them. The police are supposed to keep order.”

Angela Jackson came to vote with her husband and two little girls in tow. She voted for Jones, the former Mary Kay cosmetics sales director.

Jackson echoed the thoughts of other Ferguson residents who experienced something new in this election: candidates coming to their door. Past elections have not seen the kind of canvassing activity that took place in the last few weeks. Nor have past municipal elections drawn so much media attention.

“One thing we really liked is (Jones) came to our door and talked to us about her desire to make change in our neighborhood,” Jackson said. “She’s going to be hands on. She lives in the neighborhood as well and has for the past 36 years. We were kind of taken by that.”

The rain began to fall again as the Glenns got in their car. It was expected to continue off and on through the day and night.

But at about 5, just when many voters were leaving work, the sun shone brilliantly. Overheard at one precinct: Good weather brought out the worst in Ferguson last August. Maybe today, it would bring out the best.