UNIVERSITY PARK — Remember backyard games of Red Rover, Mother May I, and Red Light Green Light? How about playing Monopoly or Chutes and Ladders? Games like these figure into the pleasant childhood memories of many, but can games serve a larger purpose? Are games more than “child’s play”?

According to Brian Orland, Distinguished Professor of Landscape Architecture, the right type of game can lead to positive behavior change in both children and adults. “Good games are engaging; players adapt their behaviors to succeed, and they try hard to do well,” Orland said. “Isn’t that exactly the outcome we want when persuading people to lose weight, drive less or save energy in their workplace?”

Games intended to influence behavior — called “serious games” in the research arena — have gained attention as an effective way to get people to change their habits. Considered a branch of social media, they are often similar to educational games, but adults are the primary audience. While the name may sound like an oxymoron, researchers have found success using serious games in areas such as energy saving, recycling and personal health.

For researchers, the payoff of serious games is particularly alluring. “Interactive social media provide new opportunities to track, understand, enhance and optimize how and why individuals interact with their environments,” Orland explained.

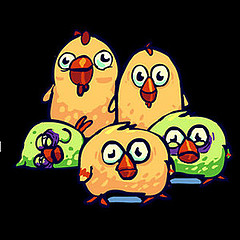

Orland is currently leading development of a serious game called Energy Chickens.

Designed by a team including current Penn State students and recent graduates, Energy Chickens is part of a Penn State-led U.S. Department of Energy grant that is funding the development of the Energy Efficient Buildings (EEB) Innovation Hub at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. After an initial pilot phase in the Stuckeman School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, the game is now being further tested by a pilot audience in Princeton, N.J. Eventually, it will be one of several energy-saving interventions implemented in commercial office buildings within the EEB Hub.

In the game, a player’s energy consumption is tied to the health of a flock of virtual chickens that live in a “barnyard” accessed via a computer icon.

During the game, which lasts over several months, a participant who cuts down on use of a real-world electrical appliance, such as a computer, lamp or fan, will be rewarded with a chicken that grows and lays eggs, which can be traded for virtual accessories. A continuous uptick in energy consumption, on the other hand, will cause chickens to become unhealthy and stop laying eggs.

Energy use, Orland explained, is monitored before and during the game via sensors attached between the chosen device and its electrical outlet. Once a baseline is established and the game is initiated, the sensors collect data at 10-second intervals. “Our chickens are very diligent and never sleep.” he noted.

Serious games provide an engaging, interactive environment for processing information, as well as immediate feedback on the impact of our decisions, he said, and, if designed properly, they’re entertaining, too. In Energy Chickens, the “chicken farmers” — or energy consumers — tend to become attached to their flock, Orland has observed: “They don’t like it when the chickens move on to a new barnyard.” The hope is that conservation lessons learned in the game will translate to real-world energy consumption.

Serious games are often designed to leverage a fundamental finding of behavioral research: that negative feedback is effective in altering people’s actions. If someone playing Energy Chickens notices her birds are looking a little sickly, the thinking goes, she will be more likely to turn off lights and electronics.

On the other hand, when a serious game targets group behavior, the focus typically shifts to positive reinforcement. During the second phase of Energy Chickens, yet to be launched, people will be able to see how other flocks are doing. “We expect people will really pull together to help the sick chickens,” Orland said. “And that’s a human trait we like to see and encourage.”

— Michele Marchetti and Amy Milgrub Marshall

Brian Orland, M.L.A., is Distinguished Professor of Landscape Architecture and can be reached at boo1@psu.edu.