New evidence that will help to answer long-standing questions about the history of stars in the disk of our galaxy is being released this week at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society by a team that includes a Penn State astronomer. The study uses data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), which has been mapping the stars in our galaxy for more than a decade. The research reveals some stars with orbits that take them to interesting places and that reveal interesting stories about how these stars were formed.

Astronomers Judy Cheng and Connie Rockosi, of the University of California, Santa Cruz, presented the information in Texas during the American Astronomical Society meeting. Donald Schneider, head of Penn State’s Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, is one of the coauthors of the study. “The SDSS results are providing another window into the structure and history of our galaxy,” said Schneider, who is the SDSS survey coordinator.

The SDSS results come from the Sloan Extension for Galactic Understanding and Exploration 2 (SEGUE-2) survey in the SDSS-III project, which has measured the motions and chemical compositions of more than 118,000 stars. Some of those stars are in the disk of our galaxy, which orbit around the center of the galaxy and which we see in the night sky as the bright Milky Way. Most of the orbits line up in a flat plane like planets around the Sun — but a few orbit to the beat of a different drummer. “Some disk stars have orbits that take them far above and below the plane of the Milky Way,” explained Connie Rockosi, an astronomer at University of California Santa Cruz, the principal investigator for the SEGUE-2 survey. “We want to understand what kinds of stars those are, where they came from, and how they got there.”

The orbits of these stars make them clearly different from mainstream Milky Way stars — and the new research shows that their chemical composition also makes them unique. Astronomers already knew that the first generation of stars consisted entirely of hydrogen and helium — then, over time, those early stars turned some of their hydrogen and helium into heavier elements, like calcium or iron — and then, when those stars died, the heavier elements they produced became part of the next generation of stars. So as new stars were born and the Milky Way disk grew, each generation had more calcium, iron, and other heavy elements.

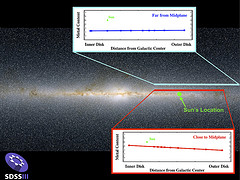

A team led by Judy Cheng of University of California Santa Cruz examined SEGUE-2 data to determine the metal content of thousands of stars in the disk of the Milky Way galaxy. The survey showed that, near the plane of the galactic disk, stars closer to the center of the galaxy have higher metal content than those farther from the galactic center. “That tells us that the outer disk of our Galaxy has formed fewer generations of stars than the inner disk — meaning that the Milky Way disk grew from the inside out,” said Cheng.

But then Cheng studied the “different drummer” stars, those that are clearly part of the Milky Way disk but show up far above or below the disk plane. She found that the amount of heavier elements in those stars doesn’t follow the same trend — everywhere she looked in that part of the galaxy, stars had low metal content. “The fact that the metal content of those stars is the same everywhere is a new piece of evidence that can help us figure out how they got to be so far away from the plane,” Rockosi says.

What we do not yet know is whether these stars were born with such strange orbits, or whether something happened in the past to put them on these unique paths. “If these stars were born with these orbits,” said Cheng, “they were born at the same rate all over the galaxy. If they were born with regular orbits, then whatever happened to them must have been very efficient at mixing them up and erasing any patterns in the metal content, such as the inside-out trend we see in the plane.” Possible explanations for such efficient mixing include long-ago collisions between our galaxy and its neighbors, or the effect of spiral arms sweeping through the disk. Cheng’s observations will help to determine whether such major events in the lives of these stars caused them to wander far from their birthplace.

Disk stars are observed far from the plane in many other galaxies, so solving the puzzle presented by these stars observed by SDSS will help astronomers to understand a basic part of how spiral galaxies like the Milky Way form.

MORE ABOUT SDSS-III

Funding for SDSS-III has been provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Participating Institutions, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Energy. The SDSS-III web site is http://www.sdss3.org/.

SDSS-III is managed by the Astrophysical Research Consortium for the Participating Institutions of the SDSS-III Collaboration including the University of Arizona, the Brazilian Participation Group, Brookhaven National Laboratory, University of Cambridge, University of Florida, the French Participation Group, the German Participation Group, the Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias, the Michigan State/Notre Dame/JINA Participation Group, Johns Hopkins University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, New Mexico State University, New York University, Ohio State University, Pennsylvania State University, University of Portsmouth, Princeton University, the Spanish Participation Group, University of Tokyo, University of Utah, Vanderbilt University, University of Virginia, University of Washington, and Yale University.