Election officials said Pennsylvania’s redesigned mail ballot envelope was a success, but state data points to a new type of voter mistake affecting rejections.

Carter Walker of Votebeat

This article is made possible through Spotlight PA’s collaboration with Votebeat, a nonpartisan news organization covering local election administration and voting. Sign up for Votebeat Pennsylvania’s free newsletters here.

Fewer mail ballots were rejected for voter errors overall in this year’s primary election, a Votebeat and Spotlight PA analysis shows, an achievement that the state credits to a modified ballot return envelope designed to help voters avoid mistakes.

But state data points to a new type of voter mistake affecting ballot rejections. And the way counties have diverged in their response to this error has opened up a new avenue for litigation ahead of November’s presidential contest.

Compared with the 2023 primary, counties rejected 9.6% fewer ballots for the kinds of errors that the redesign sought to address: a missing date or signature on the return envelope, an incorrect date, or ballots returned without an inner secrecy envelope. (See the methodology for the data analysis at the bottom of this article.)

“I think it is clear that the ballot redesign resulted in fewer voters making errors,” Secretary of the Commonwealth Al Schmidt said.

Pennsylvania’s Election Code requires that mail voters place their ballot in a secrecy envelope before placing it in the return envelope. They must then sign and date the return envelope.

But since Pennsylvania implemented its no-excuse mail voting law, Act 77, in 2020, thousands of ballots have been rejected because of procedural errors by voters, such as missing dates and signatures. Courts have gone back and forth on which errors should cause a ballot to be rejected. So far, the divided legislature hasn’t successfully stepped in to clarify the rules.

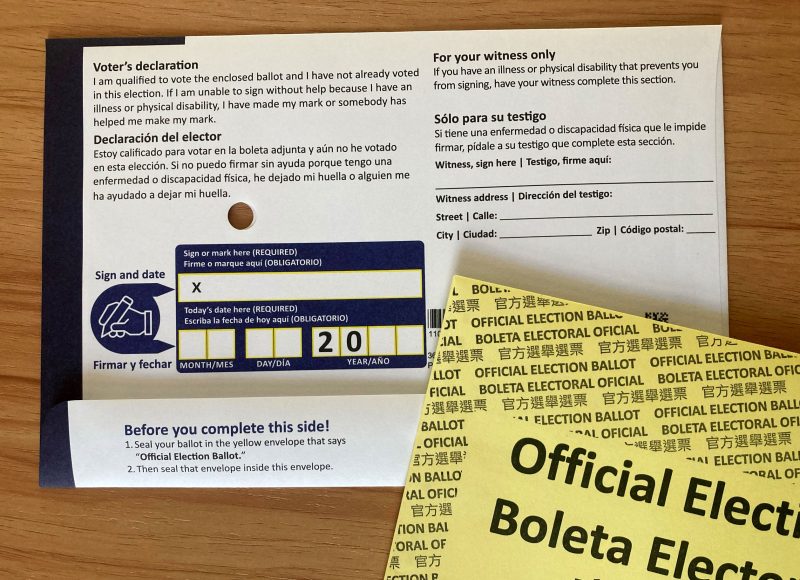

After the 2023 municipal elections, the Department of State announced a redesigned ballot return envelope that it hoped would cut down on the number of rejected ballots. The April 23 primary was the first to see that envelope used.

But with the redesigned envelope, officials noticed a new error cropping up: voters who put a date on their envelopes but left the year only partially filled in. Some counties rejected those ballots on that basis, while others, heeding advice from state officials, accepted them.

Redesign made date and signature box stand out

The Department of State’s redesign of the mail ballot return envelope sought to address four of the most common errors that require counties to reject ballots: a missing date, an incorrect date, a missing signature, or a ballot not returned in a secrecy envelope.

In the new design, the area where a voter is to sign and date the envelope is shaded, to make it stand out, and it has the digits “20” prefilled for the year, to prevent voters from writing their birth date. Secrecy envelopes were also changed to yellow and included new watermarks to make them stand out.

Overall, the rate of ballots rejected for these reasons, as a proportion of all mail ballots returned, went down, which officials claim as success for the new design. But when the categories are broken apart, the success of the effort is less clear.

The rejection rate for ballots lacking a date or being returned without a secrecy envelope went down. But the rates for those returned with an incorrect date or no signature went up, and those errors now represent a greater proportion of rejected ballots.

In the 2023 primary, they were the third and fourth most common errors that led to ballot rejection. Now they are No. 1 and 2. Aside from voter errors, the top overall reason for rejection in both elections was ballots that arrived after Election Day.

There are some limitations to the more detailed data. Schmidt noted that the system counties use to track mail ballots allows them to enter only one code denoting the reason for rejection. So if a ballot lacks both a signature and a date, they can record it as rejected for only one of those reasons.

He added that there is not a consistent method across counties for what order to check for errors, and which code to use first. Some counties might also change the order in which they check the fields from year to year.

“That’s why the overall number is most reliable in my opinion,” he said.

In the 2023 primary, 1.35% of returned ballots were rejected for the four reasons that the redesign sought to address. That rate dropped to 1.22% for April’s primary, according to Votebeat and Spotlight PA’s analysis. In total, just under 16,000 ballots were rejected, for any reason.

A date detail: The last two digits of the year

One feature of the redesigned envelope was a date field with the first two digits of the year — “20” — prefilled. But as Election Day approached, voters were returning ballots without writing “24” after the prefilled “20.”

On the Friday before the election, Deputy Secretary for Elections Jonathan Marks sent an email to counties advising them to count ballots even if the envelope didn’t have the last two digits of the year. Courts have interpreted the state’s dating requirement to mean it needs to have a date between when the ballot was sent to the voter and Election Day.

“It is the Department’s view that, if the date written on the ballot can reasonably be interpreted to be ‘the day upon which [the voter] completed the declaration,’ the ballot should not be rejected as having an ‘incorrect’ date or being ‘undated,’” Marks wrote.

Not all counties followed that advice.

Colin Sisk, Beaver County’s election director, said that the county viewed the department’s choice to prefill the “20” in the year field as an indication that the voter was meant to fill in the year section. He also said that if a voter last year had only written “20” for the year, the ballot likely would have been rejected, as it would have been assumed they meant 2020. So for consistency, the county chose not to accept the ballots.

The advice also came late in the election cycle.

“I know a lot of us [directors] were like ‘Holy crap, this is late’ and ‘Holy crap, this change is something that can be litigated,’” Sisk said of his reaction when he received the email on April 19, four days before the election.

Sisk was right. A candidate sued Luzerne County over its decision to count the ballots, and the Centre County GOP did the same there.

The Court of Common Pleas judge hearing the Centre County case dismissed it Friday as improperly filed, without addressing the county’s decision to count the ballots. In Luzerne County, the judge ruled the county was correct to count the ballots, but that decision is now on appeal in Commonwealth Court.

Counties were split over whether or not to accept the ballots, and that decision appears to have had an impact on their rejection rate.

Votebeat and Spotlight PA looked at 36 counties that had suitable data to determine the change in rejection rates from year to year. Among them, counties that decided to count ballots with a missing “24” for the year had lower average rejection rates than in the previous primary election, while counties that chose not to count these ballots on average had virtually no change in the rejection rate, and most saw an increase.

“I think they were trying to make it easier for people so they didn’t put their birth year, but it confused people in my opinion,” said Karen Lupon, chief clerk and election director for Jefferson County, although she added she thinks the redesign was successful in reducing “naked ballots” that were returned without a secrecy envelope.

November is the next big test

The Department of State would not say whether it plans to make any changes to the envelope before the November election as a result of the issue.

Whether the lower rejection rate holds in November will be the next big test, both for the redesigned envelope and recent educational efforts from the department, campaigns, and other groups looking to inform them on how to properly cast their ballot.

“It’s a good sign to see rejections going down,” said Kyle Miller, a policy advocate with the nonpartisan group Protect Democracy. “I’m really interested to see what happens in the general, when you have more casual voters.”

Compared with general election voters, those who participated in April’s primary — during which many high-profile races were uncontested — were more likely to be tuned into the rules and educational efforts.

At least one county foresaw the missing “24” as an issue. In Bucks County, election officials opted to preprint the full year on the ballot, rather than just “20” as the Department of State recommended.

“As a result, I think we saw lower numbers of errors on the date than we would have,” Bucks County Solicitor Amy Fitzpatrick said at an April 30 election board meeting.

Lycoming County may follow suit. Its election director, Forrest Lehman, said he has been in contact with the vendor who prints his return envelopes to ask if it would be possible to add the “24” on envelopes that were already printed.

The issue could be moot come November if the ACLU of Pennsylvania and Public Interest Law Center prevail in their lawsuit seeking to nullify the requirement that voters write a date on the return envelope.

About this Data: The Department of State calculated the reduction in the rejection rate from the 2023 primary to the 2024 primary to be 13.5%. The department used a method of analysis that adjusted rejection figures from the 2023 primary to match what they likely would have been had that election seen the same turnout as 2024. After consultation with several political scientists who regularly analyze election data, Votebeat and Spotlight PA opted to use a different method that directly compared the actual rejection percentage from each election, though the political scientists said both methods are legitimate. Votebeat and Spotlight PA’s calculation also included ballots marked with “pending” codes in the state’s mail ballot tracking system, which the Department of State did not. All but one county had certified its election at the time of Votebeat and Spotlight PA’s analysis, which was not the case at the time the department opted to exclude “pending” ballots.

BEFORE YOU GO… If you learned something from this article, pay it forward and contribute to Spotlight PA at spotlightpa.org/donate. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.