Affected homeowners in Benner Township, Centre County, want to know when and how PFAS chemicals got into their water. State officials defend the delay, pointing to “sound scientific practices.”

Adam Smeltz for Spotlight PA State College

This story was produced by the State College regional bureau of Spotlight PA, an independent, nonpartisan newsroom dedicated to investigative and public-service journalism for Pennsylvania. Sign up for our regional newsletter, Talk of the Town.

BENNER TOWNSHIP — A class of synthetic chemicals identified in 2019 near Penn State University’s airport has fouled tap water in an adjacent neighborhood, and families there are now demanding to know why it took environmental officials so long to test their wells, which they use for bathing, cooking, and drinking.

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection began providing bottled water this year to at least nine households where well water registered above a longstanding federal health advisory threshold for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, known as “forever chemicals” for their inability to break down naturally.

But as the DEP investigation in Benner Township, Centre County, approaches its third anniversary, Walnut Grove Estates residents want to know why the state didn’t start checking their wells until December — and they worry what the contamination means for their health.

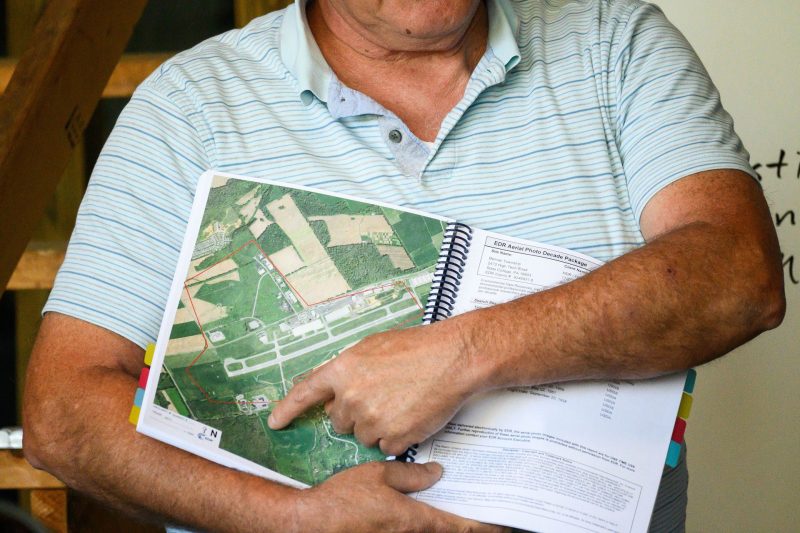

“It went way, way, way too long,” said Gene Stocker, 71, whose home borders the airport’s southeast grounds.

Stocker floated the idea of testing residential wells as early as April 2021, when a DEP manager replied that sampling efforts were in the works but that home tests would be premature “without a sampling plan in place,” according to emails he shared with Spotlight PA.

As of late May, at least 41 of 50 home wells in the investigation area showed some amount of PFAS, 11 of them recording levels above the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s advisory threshold at the time. One of the 11 was connected to a vacant house; the other already had advanced filtration.

The EPA has since lowered advisory levels for several PFAS substances.

In a written response to questions from Spotlight PA, the DEP defended its timeline for testing, saying Walnut Grove Estates is more than a half-mile from its initial focus, “on the other side of a surface water and presumed groundwater divide.”

“DEP understands that residents are frustrated, but it is important to understand the process and pace of such an investigation is influenced by many factors, with the primary consideration being sound scientific practices to ensure that any results, and therefore follow-up actions, are sound,” the department wrote.

It’s unclear how long residents in the affected neighborhood have been drinking contaminated water. The DEP has declined to specify the most likely source as it continues to examine the pollution’s scope and origins. Responsibility could mean costly legal liability, though a lack of regulation around PFAS could limit what entities or businesses could be held accountable.

“DEP has not discovered any indications to date that the PFAS contamination is anything more than the result of historic practices conducted in accordance with applicable requirements at the time,” the department said.

An investigative report from June 2021 identifies firefighting foam as a potential PFAS contamination source at the airport, which operates under Penn State oversight. The report also explores industrial, technology-related, and military land uses in the roughly 11.5-square-mile study area.

The university said in a written response to questions from Spotlight PA that a firefighting foam could have contaminated groundwater at the airport, but added the airport has “maintained stringent compliance with regulations.”

“Given how prevalent PFAS use is in manufacturing processes, in addition to their presence in fire-fighting foam, there could be one or more sources of contamination from businesses in the area, either current or past,” Penn State wrote.

PFAS chemicals appear in hundreds of consumer and industrial products, from nonstick pans to firefighting foams, and face growing scrutiny for potential health effects including cancers, liver damage, and fertility issues. A recent study in the medical journal Hypertension found the chemical might also be linked to higher blood pressure in women.

Once ingested, the chemicals can stay in the human body for years.

“We will need to monitor our health for the rest of our lives,” said Kevin Hulburt, 43, who moved to Walnut Grove Estates with his wife and young kids in August 2020, oblivious to PFAS contamination that was then registering in groundwater at the airport.

His children are his biggest worry, he said. He and his wife had been pursuing a healthy lifestyle by growing a garden and raising quail — all with the same water they were drinking themselves. They switched to bottled water when high PFAS levels appeared in their well’s test results in April.

A standard test for well contaminants did not check for PFAS when they bought the property, Hulburt said.

“We wanted to provide for [the kids] the best lives we can. To know we have inadvertently been poisoning them is really hard to process,” he said. “And to know these forever chemicals stay in their bodies forever is really my No. 1 concern — and how do we keep them safe, like every parent is worried about.”

In the human body, it takes about four years for levels of certain common PFAS to drop by 50%, according to the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. That assumes no additional exposure.

Health concerns

To protect their community from PFAS, residents want a municipal water source for Walnut Grove Estates, a small, rural neighborhood located a 10-minute drive from Penn State’s University Park campus, as well as a few nearby affected homes. On June 28, DEP will solicit public input on the state’s initial response, which includes offers of whole-house carbon filtration systems for homes with the worst well contamination.

Longer-term options under review by DEP include connecting Walnut Grove Estates to a public water system, according to the department. The expense would fall to the party responsible for the contamination — if investigators identify that party, the DEP said in a statement.

Meanwhile, residents said they worry whether past ailments, including cancers and thyroid issues, and future health risks could be tied to their water. When Stocker had his blood serum evaluated in March, one PFAS chemical appeared around four times the norm, according to results he provided to Spotlight PA.

The chemical — known as PFHxS — is exceptionally toxic and has been part of a foam used widely in firefighting exercises at airports, said Linda Birnbaum, former director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The PFAS family affects a variety of bodily tissues, she said.

“It’s not just the liver and not just the kidney and not just the cardiovascular system,” Birnbaum said. “It’s also bone, pancreas, brain. You name it — there is growing evidence.”

A longtime car dealer in the county, Stocker alleged “gross negligence” over the contaminated water, which he fears his family and neighbors were drinking for years. Three generations of Stockers live in the neighborhood.

Levels of two PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, appeared in Stocker’s well at a combined 194.8 parts per trillion in test results reported in February. That’s more than double the health advisory level of 70 parts per trillion set by the EPA in 2016.

A filtration system installed at Stocker’s home several years ago appears to be keeping PFAS under that threshold for water used indoors, he said. The family bought the system after tests in 2016 identified another contaminant, ethylene dibromide, in the well.

The EPA this month issued new advisories for four PFAS chemicals, cautioning that negative health effects may be possible even at PFOA and PFOS concentrations near zero. An advisory level is a point beneath which researchers would not expect damaging health effects.

It wasn’t immediately clear how the adjusted advisories might affect the DEP response in Benner Township.

“Everybody knows that 70 [parts per trillion] is too high,” said Dr. Alan Ducatman, a PFAS researcher and professor emeritus in public health at West Virginia University. “It’s very clear that those of us with higher doses are more at risk.”

Scientists don’t know the smallest PFAS exposure for which there would be no health consequences, but people who have PFAS in their water face the greatest hazards, Ducatman said.

At a June neighborhood discussion hosted by Stocker, county Commissioner Steve Dershem pledged to advocate transparency — including from Penn State — as the DEP finalizes a comprehensive investigative report it expects to release in the fall.

“If it was my house, I’d be sitting in your seat fuming probably twice as much,” Dershem told about 50 residents at the event.

In a previous interview, he told Spotlight PA that residents deserve answers.

No matter where the contamination began, a relative lack of regulation around PFAS may limit mechanisms for cleanup and accountability, especially in the short term, according to environmental law experts. EPA advisory levels are not enforceable guidelines, but the agency is pursuing a “hazardous” designation for two PFAS substances under the federal Superfund law.

The change would open the door for mandatory disclosure and other regulatory standards around contamination, including the potential for recovering cleanup costs from responsible parties. In Pennsylvania, the DEP is working toward PFOA and PFOS limits for public drinking water supplies at a fraction of 70 parts per trillion. The state standard would be incorporated into monitoring and other mandates.

“It’s always going to be easier for a homeowner to get accountability from someone — whether it’s the government or an actual responsible party — if an agency charged with protecting public health and welfare has decided this is a problem,” said Charlie Howland, an adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School and a former EPA lawyer.

Now in private practice, Howland said some liability claims will become easier if the EPA designates PFAS as hazardous under Superfund. The DEP directed Walnut Grove Estates homeowners to disclose any contamination above 70 parts per trillion as part of their public property records.

Investigation origins

From 2019 to 2021, the DEP set out to get a better sense of PFAS contamination across Pennsylvania, taking samples from more than 300 water supplies statewide. The department picked locations based on their proximity to common sources of PFAS, such as military bases, fire training sites, landfills, and manufacturing facilities, the DEP said.

Its well tests in 2019 revealed high levels of PFAS — above the EPA’s health advisory limit at the time — at three businesses near University Park Airport, according to the June 2021 report released by the department.

Wells at manufacturers State of the Art and Matreya LLC, and parking and storage company Handy Delivery sit roughly northwest of the airport. At Handy Delivery, company Vice President Jeff Byers said the DEP recommended against drinking tap water after the well test there in November 2019.

“It hasn’t impacted us all that greatly. We’re not thrilled about it, obviously,” Byers said. “For us, it’s not a huge inconvenience to not drink out of the faucets. That’s the only change here.”

State of the Art and Matreya did not respond to requests for comment. Their wells were sampled in August 2019 and November 2019, respectively.

The 2021 report, prepared for the DEP by Mechanicsburg-based engineering firm HDR, mentions that those sites host or have hosted manufacturing activities. Other businesses may have been involved in manufacturing activities in the vicinity, too, according to the report.

By early 2020, Penn State was sampling wells in the airport area as the DEP review expanded. In June and August that year, a well on the airport’s northwest edge returned PFAS levels above the 70-parts-per-trillion threshold, the report notes.

Airport workers have used a specialized foam — aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF — to test firefighting equipment twice a year, in line with Federal Aviation Administration regulations, according to the report.

PFAS in such foams help suppress fire, but they have become a frequent source of contamination. In fact, airports and military defense facilities are the most common sources of PFAS pollution, said Ducatman, the PFAS researcher and a professor emeritus in public health at West Virginia University.

“But they are generally not the worst sources,” Ducatman said. “Industrial sources, where they exist, can be worse. And Pennsylvania certainly is an industrial state.”

Before 2006, film-forming foam was discharged to the ground in two “probable locations” at University Park Airport, according to a Penn State account in the HDR report. One location is a grassy area at the northeastern corner of the 1,100-acre airport property; the other is between a taxiway and an area used for deicing planes.

“There are no records of how much PFAS-containing firefighting foam was used for training over the years,” DEP said in response to questions from Spotlight PA.

From 2006 to 2018, FAA-required tests of firefighting equipment happened mainly in a deicing area, Penn State wrote in a separate statement. The deicing pad was washed down, with runoff collected in tanks for disposal at a wastewater facility in Bellefonte.

The airport stopped sending those materials to the treatment plant in 2018, Penn State reported. Since about 2009, the airport hasn’t allowed the foam to be released to the ground, collecting it for “appropriate disposal,” according to the university. Since 2020, airport personnel have placed the used foam in an on-site containment tank, where it remains until a third party takes the material away, according to the HDR report.

“Training exercises no longer involve AFFF, and only water is used,” Penn State said in response to questions from Spotlight PA.

Firefighters at the airport have been using the foam to extinguish flammable-liquid fires from aircraft crashes, according to Penn State. The airport stores foam in a building used by the aircraft rescue and firefighting team, HDR noted in its report.

A new rescue and firefighting vehicle will feature “a testing system that contains all firefighting foam internal to the vehicle,” Penn State wrote. Commercial airports must address PFAS contamination because of the FAA’s requirement to use the foam, the university said.

“There are currently no FAA-approved alternatives to firefighting foams that do not contain PFAS,” the university wrote. “As new alternatives and equipment are evaluated and approved, Penn State will look to adopt these new technologies.”

Groundwater patterns

Residents bristle at the two-year gap between the initial contamination discovery and the well tests in Walnut Grove Estates. Many had no idea their water supplies might be at risk until concerns over the airport started circulating in the neighborhood about six months ago, they said.

The DEP told Spotlight PA that it offered to sample wells at Walnut Grove Estates during a Benner Township meeting in November 2021. After an initial round of residential well sampling in December 2021, the department hand-delivered letters seeking permission to test more, it told Spotlight PA. Initial indicators had not signaled PFAS movement toward the neighborhood, but the investigation “expanded outward and located this area of concern,” the agency said.

Although groundwater in the area generally flows from the southwest to the northeast, that pattern can vary, said David Yoxtheimer, a hydrogeological consultant in the region for nearly 30 years. Walnut Grove Estates sits east and slightly south of wells that first tested high for PFAS, on the opposite side of the airport.

“Where the airport sits is a high spot,” said Yoxtheimer, who also is a Penn State faculty member. Water has “a radial flow out from this high spot. You have the potential for flow to radiate away from this groundwater mound.”

The region’s limestone-rich geology, called karst, allows for variations in flow, he said. He cast it as “a relatively complicated plumbing system.”

“In a karst situation, you should always expect the unexpected when it comes to groundwater flow and this kind of limestone bedrock,” Yoxtheimer said.

In its defense, the DEP noted that more than two-thirds of a mile separate the contaminated airport well and the neighborhood. The homes are more than four-tenths of a mile from the closest testing area where the university reported use of firefighting foam, the DEP said.

The agency asserted it was always aware of the Walnut Grove Estates area “and planned to investigate if the initial investigation results led us in that direction.”

By late May, the DEP had collected samples from some 55 wells overall. Sampling is likely to continue through the summer. The DEP wouldn’t predict how many additional wells might be checked, but said it tested, or was testing, all residential and business wells where property owners wanted the information.

Its plans include surface-water sampling of Spring Creek, a celebrated trout stream. A precautionary test of a well field operated by the State College Borough Water Authority near the airport detected no PFAS in March 2021, said Brian Heiser, the authority’s executive director.

A check there in August 2019 came back at a combined 3.6 parts per trillion, he said — well less than proposed limits in Pennsylvania. Related tests at an authority well in Ferguson Township yielded similar results, turning up no PFAS in 2021, he added.

The authority doesn’t have any immediate concern about the well field closest to the airport, “but we are continuing to monitor it and monitor the situation with DEP,” Heiser said.

While research shows nearly all Americans have some PFAS in their blood, those with exposure to high contamination may want to take particular precautions, experts warned. Measures may include testing the body for PFAS levels, which can inform medical monitoring over the longer term.

Hazards like smoking are a greater menace to health, noted Ducatman. But PFAS exposure is different because it’s involuntary.

“It’s like taking a medication that nobody prescribed for you,” Ducatman said. “All you can get are side effects. And you’re taking it every day unknowingly.”

Adam Smeltz is a freelance contributor to Spotlight PA State College. He is a former staff reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, and the Centre Daily Times.

SUPPORT THIS JOURNALISM and help us save local news in State College and north-central Pennsylvania at spotlightpa.org/statecollege. Spotlight PA is funded by foundationsand readers like you who are committed to accountability and public-service journalism that gets results.