President Trump has again accused America’s NATO allies of falling behind on their bills.

“Twenty-three of the 28 member nations are still not paying what they should,” Trump told heads of NATO states assembled Thursday in Brussels. “Many of these nations owe massive amounts of money from past years.”

It’s not the first time Trump has suggested other NATO members have a debt to pay.

But NATO does not keep a running tab of what its members spend on defense. Treaty members target spending 2% of economic output on defense — but that is merely a guideline.

NATO members spend money on their own defense. The funds they send to NATO directly account for less than 1% of overall defense spending by members of the alliance.

Here’s how it works:

National budgets

NATO is based on the principle of collective defense: an attack against one or more members is considered an attack against all. So far that has only been invoked once — in response to the September 11 attacks.

To make the idea work, it is important for all members to make sure their armed forces are in good shape. So NATO sets an official target on how much they should spend. That currently stands at 2% of GDP.

The 2% target is described as a “guideline.” There is no penalty for not meeting it.

It is up to each country to decide how much to spend and how to use the money.

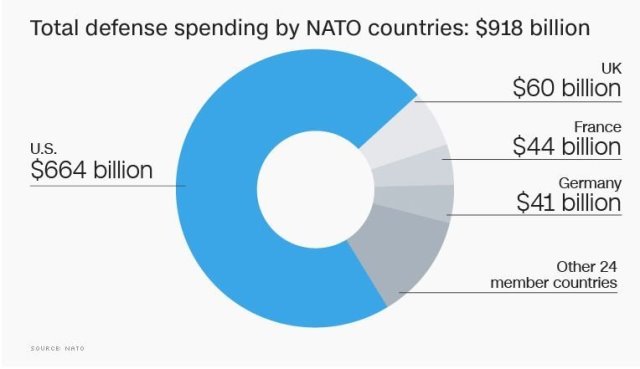

The North Atlantic alliance has its own military budget worth €1.29 billion ($1.4 billion), which is used to fund some operations and the NATO strategic command center, as well as training and research. But it is miniscule compared to overall spending on defense by NATO countries, which NATO estimates will total more than $921 billion in 2017.

The alliance also has a civilian budget of €234.4 million ($252 million), used mainly to fund the NATO headquarters in Belgium, and its administration.

Spending is rising

Only five of NATO’s 28 members — the U.S., Greece, Poland, Estonia and the U.K. — meet the 2% target.

The rest lag behind. Germany is set to spend 1.2% of GDP on defense this year, France 1.79%. Belgium, Spain and Luxembourg all spend less than 1%.

NATO has long been pushing for higher spending. At a summit in 2014, all members who were falling short promised to move toward the official target within a decade.

That pledge appears to be holding: The alliance as a whole increased defense spending for the first time in two decades in 2015.

And last year, 22 of 28 NATO members increased their defense budgets. If the U.S. is removed from the equation, the group increased its spending by 3.8% in 2016. Including the U.S., overall spending rose by 2.9%.

Fear of Russian aggression is driving some of the recent splurge. Latvia, which shares a border with Russia, increased its defense budget by 42% in 2016. Its neighbor Lithuania boosted its outlays by 34%.

The 2% problem

So why don’t more countries spend 2% of GDP? Many experts point out that the target is problematic.

NATO has warned against a rush to spend for the sake of spending, emphasizing that budget decisions must be based on strategic planning. For example, it wants countries to spend 20% of their defense budgets on equipment.

There’s also pressure for more coordination of spending among European countries.

Some member countries simply don’t have armies big enough to be able to absorb a huge increase in funding quickly — that’s why the 2014 summit pledge gave laggards until 2024 to do more.

NATO member Iceland, for example, doesn’t have its own army and spends just 0.1% of its GDP on defense, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

And the 2% target doesn’t just cover spending on defense to meet NATO commitments. The money can be used to fund other activities such as European peace missions in the Central African Republic and Mali, as well as national missions that are not part of NATO operations, for example the fight against ISIS.