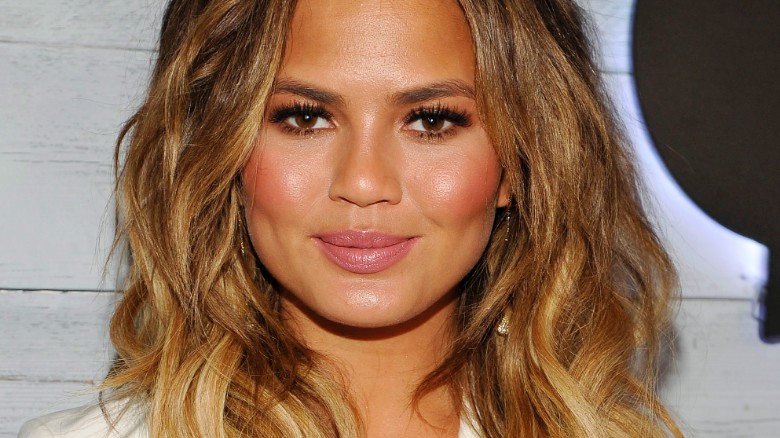

Model, television host and social media maven Chrissy Teigen has developed a reputation as a person who is willing to talk about just about anything in Twitter posts to her more than 4.5 million followers. But she has been silent about one topic until now: Her own struggle with postpartum depression and anxiety, which affects as many as one in seven women in the United States, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

In an essay for Glamour magazine, Teigen shares how she got the diagnosis before the holidays, several months after giving birth to her daughter, Luna, in April.

“Before this, I had never, ever — in my whole entire life — had one person say to me: ‘I have postpartum depression,’ ” writes Teigen, who is married to Grammy- and Academy Award-winning singer-songwriter John Legend.

She said she associated it with people who didn’t like their babies or felt like they had to harm their children, people like Susan Smith, who was convicted in the drowning deaths of her two young sons in South Carolina in 1995.

“I didn’t have anything remotely close to those feelings. I looked at Luna every day, amazed by her. So I didn’t think I had it,” she writes.

What she had were months of mental and physical struggles. Getting out of bed was painful. She didn’t have an appetite. She’d lose it on the set of her show “Lip Sync Battle” and burst into tears. Eventually, she left the house only when she had to go to the studio. Soon, she couldn’t make her way upstairs to bed and spent most of her days on the exact same spot on the couch.

“I couldn’t figure out why I was so unhappy. I blamed it on being tired and possibly growing out of the role: ‘Maybe I’m just not a goofy person anymore. Maybe I’m just supposed to be a mom,’ ” she wrote.

Teigen also said she didn’t think a diagnosis of postpartum depression could happen to her.

“I have a great life. I have all the help l could need: John, my mother (who lives with us), a nanny. But postpartum does not discriminate: I couldn’t control it. And that’s part of the reason it took me so long to speak up: I felt selfish, icky, and weird saying aloud that I’m struggling. Sometimes I still do.”

Teigen said that at the time she wrote the essay in February, she was already a “much different human,” with one month of an antidepressant under her belt and with the name of a therapist she planned to see.

After her essay was published Monday, she shared a picture on Twitter of herself and her husband along with daughter Luna. Teigen and Luna held up a sheet of paper that said #LoveMeNow, also the name of a recent hit of Legend’s that features Teigen and Luna in the music video.

Teigen thanked Glamour for the chance to tell her story.

She says she’s prepared for backlash from people who think she might sound like a “whiny, entitled girl.” Plenty of people in her situation have no help, no family and no access to medical care, she writes: “I can’t imagine not being able to go to the doctors that I need.”

Women most in need often don’t get help

In fact, it is women in low-income communities who are more at risk for postpartum depression or any other form of pregnancy-related mental illness during or after pregnancy, according to research. The spectrum of illnesses impacting women goes beyond depression to include anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder and, in the rarest and most serious cases, postpartum psychosis. That affects just one or two of every 1,000 new mothers.

According to a 2008 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, mothers who received Medicaid benefits for their delivery, mothers with less education and younger women were the groups most likely to report postpartum depressive symptoms. A 2010 study by the University of Rochester Medical Center, published in the journal Pediatrics, found that more than 50% of low-income mothers living in urban areas met the criteria for a diagnosis of depression at some point between two weeks and 14 weeks after delivery.

And yet for a host of reasons including access, financial barriers, stigma and cultural differences, these mothers are often not getting the treatment they need.

“I have had African-American friends tell me — so it was firsthand — they were on the receiving end of messages including ‘That’s a white woman’s disease. We don’t get that,’ ” said Lynne McIntyre, herself a survivor of postpartum depression and founding manager and consultant to the maternal health program at Mary’s Center for Maternal and Child Care in Washington, D.C., in 2015.

Women in low-income communities may also not step forward to seek help out of fear of what might happen to their babies.

“There’s a fear that if one opens up … that child protective services would become involved, and it’s not uncommon for women to fear the extreme that their children will be taken away from them,” said Dr. Judy Greene, a reproductive psychiatrist at NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue Hospital Center in New York.

Celebrities help raise awareness

Teigen joins a list celebrities who have come forward to open up about their bouts with postpartum depression such as singer-songwriter Adele last year and actress Hayden Panettiere, who revealed that she entered treatment for postpartum depression in 2015.

When celebrities open up, it helps raise awareness, but there is still much more to be done, experts say.

“People come to me and say, ‘I’m a social worker, and I suffer from postpartum depression, and I had no idea,’ so if a social worker’s telling you that, we know there is a problem. We have a crisis on our hands,” said Nitzia Logothetis, founder and interim CEO of the Seleni Institute, a nonprofit focused on serving the reproductive and maternal mental health care needs of women.

“So I think it’s really about changing the conversation and getting the word out, educating people,” she said in 2015.

Teigen hopes that by sharing her story, she is letting people know that postpartum depression, anxiety or any other pregnancy-related mental illness can happen to anybody.

“I don’t want people who have it to feel embarrassed or to feel alone,” she said. “I also don’t want to pretend like I know everything about postpartum depression, because it can be different for everybody. But one thing I do know is that — for me — just merely being open about it helps. This has become my open letter.”