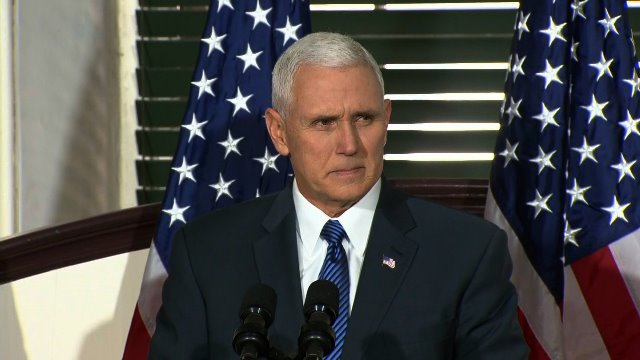

As Vice President Mike Pence darted from meeting to meeting this weekend in Europe, one phrase was on repeat.

“The President sends greetings,” he told European High Representative Federica Mogherini over breakfast in the dining room of the US ambassador to the EU.

“I bring greetings from President Donald Trump,” he noted to Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel in front of an ornately carved mantelpiece at the Chateau de Val-Duchesse, a former priory.

“It is a privilege to be here to bring greetings on behalf of President Donald Trump,” he declared to European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, standing in the commission’s lobby as European bureaucrats bustled to and fro.

Everywhere he traveled on his first foreign tour, which wrapped up Monday, Pence was intent on reminding his interlocutors who he was there representing — though there’s little doubt European leaders have forgotten about the man back home.

Sent to Europe on a reassurance tour just as the national security apparatus at the White House spiraled into disarray, the vice president was assuming the same steadying role on the foreign stage he’s played domestically since Trump tapped him as a running mate: an envoy to parties who want and need contact with the administration but are wary of getting too close to Trump himself.

He’s maintained a similar relationship with congressional Republicans eager to capitalize on majorities in the House and Senate but cautious of associating too closely with a President prone to anger and insults.

And, as on his near-daily visits to Capitol Hill, Pence found in Europe that leaders and diplomats were eager for a US representative more conversant in matters of policy.

He’s not alone in the role — Defense Secretary James Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson were both dispatched last week to stand in for Trump and ease allies’ concerns.

For Trump’s global envoys explaining the new US leader has meant buffing the rougher edges of his pronouncements and turning them into cogent expressions of US policy. At other moments, it’s meant contradicting him outright, leading to confusion about where precisely US policy stands in the young days of the Trump presidency.

Flying into Baghdad Monday, Mattis told reporters the US wasn’t entrenched in the country to pillage its resources.

“We’re not in Iraq to seize anybody’s oil,” Mattis said, implicitly rebuffing a suggestion Trump himself made while visiting the CIA during his first full day in office.

The declaration, which keeps the US from the possibility of committing a war crime by pilfering another country’s assets, might have seemed unnecessary in another era. Now, such utterances are a requirement for officials hoping to maintain alliances around the world.

In an era when Trump’s Twitter feed is as closely monitored in foreign capitals as diplomatic memos and communiqués, the divergent — sometimes wholly contradictory — messages have proven troubling for even the staunchest US allies. And try as Pence and his fellow members of the Cabinet did on their weekend trips to reinforce traditional US priorities, they still couldn’t roll back all of the international consternation at hearing shifts in US policy uttered by Trump.

France’s foreign minister expressed frustration this week about the changing US stance on Middle East peace after a meeting of foreign ministers, including Tillerson.

Trump said during a news conference with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu last week that he wasn’t glued to a two-state solution in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, only to be contradicted a day later by his UN ambassador Nikki Haley, who said the US was still committed to the longstanding foreign policy goal.

“There are no other options other than the perspective of a two-state solution, and that the other option which Mr. Tillerson brought up was not realistic, fair or balanced,” said the French official, Jean-Marc Ayrault, without specifying what precisely Tillerson had suggested.

That criticism came after a low-key diplomatic debut for Tillerson, who arrived on the job at the beginning of this month with little experience in direct government-to-government talks with foreign leaders. State Department aides were so late in confirming Tillerson’s attendance at one point that he was forced to stay 30 minutes away, at a sanitarium with elderly Germans working to improve achy joints.

At the G20 ministerial meeting in Bonn, Tillerson worked like Pence to project calm in front of anxious allies. But his stature in the Trump administration wasn’t yet clear to other diplomats attending; he hadn’t been consulted on the shift in Israeli-Palestinian policy before he departed on the trip, though he has been influential in convincing Trump to accept the longstanding “One China” policy that is the basis of US relations with Beijing.

Pence, meanwhile, assumed a higher profile. His speech to the Munich Security Conference was closely watched as the administration’s first major foreign policy address, and text of the 20-minute remarks was mined for clues about what direction Trump plans to take global affairs.

White House aides said Pence spoke in detail about his planned talks with Trump before departing for Europe on Friday, and the two men spoke regularly throughout the weekend, as Pence engaged in rapid-fire diplomacy while Trump interviewed national security adviser candidates at his estate in Florida.

Pence predecessor Joe Biden was himself an avid diplomat. Early in their tenure, President Barack Obama and Biden agreed the vice president would take responsibility for distinct foreign policy portfolios — Iraq, Central America and Ukraine among them. During his final year in office, Biden took to reciting the exact number of miles he’d flown on Obama’s behalf.

But it isn’t clear that Pence has been given clear international responsibilities, and Pence doesn’t have as robust a foreign policy background as Biden did when he entered office. Pence did, however, serve on the House Foreign Affairs Committee during his tenure as a US congressman and traveled on a regular basis to Iraq and Afghanistan on official trips.

Administration officials said they envision Pence taking on foreign assignments on a case-by-case basis, hoping to develop preliminary ties or lay the groundwork for deals that Trump can finalize with his counterparts. His visit to NATO headquarters on Monday was a precursor to Trump’s own attendance at a NATO summit in Brussels this May, and Pence has already accepted an invitation to visit Tokyo this year ahead of Trump.

But even if the men are aligned behind the scenes, outwardly their differences are plain.

As he worked to assuage the concerns of leaders like German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, Pence found himself competing for attention with his boss, who held a testy news conference on the eve of Pence’s departure and convened a rollicking campaign rally on Saturday.

While Pence professorially explained to leaders gathered for the Munich Security Conference that the US expects its NATO allies to scale up their defense spending, Trump was offering a less-honed message to an airplane hanger stuffed full of supporters in Melbourne, Florida.

“I’m a NATO fan, but many of the countries in NATO, many of the countries that we protect, many of these countries are very rich countries,” Trump told his crowd. “They’re not paying their bills. They’re not paying their bills. They have to help us.”

Pence’s somber tour of the prison yard at the Dachau concentration camp also provided a contrast with Trump, who last week downplayed a rise in anti-Semitic acts in the US. Given the opportunity at two separate news conferences to speak out against a spike in anti-Jewish incidents, Trump instead grew combative, arguing the questioners were seeking to undermine his presidency.

Speaking after meeting with Pence in Brussels on Monday, European Council President Donald Tusk was bluntly skeptical of how much cooperation he should expect from Washington over the next four years, despite what he said were firm assurances from his US visitor.

“Too much has happened over the past months in your country, and in the EU; too many new, and sometimes surprising, opinions have been voiced over this time about our relations — and our common security — for us to pretend that everything is as it used to be,” Tusk said in an unusually frank statement after a meeting with a foreign leader.

Tusk said Pence had offered reassurance on his areas of concern — security cooperation and US commitment to an integrated EU — but the European Council President didn’t depart entirely persuaded.

“After such a positive declaration,” Tusk said, “both Europeans and Americans must simply practice what they preach.”