Their fathers were killed on 9/11, and 15 years later they carry a message: Look at us, more resilient than ever.

To the terrorists, they say, “You lose.”

“We’re still here,” says Patrick Hannaford, who was 2 years old when his father, Kevin Hannaford, 32, was killed on the 105th floor of the World Trade Center’s north tower, where he worked for Cantor Fitzgerald. “We’ve rebuilt, and we’re stronger now than we were then. It’s just a good feeling to know they failed.”

“All of us are sitting here — successful, intelligent,” says Jessica Waring, 29, who lost her father, James Waring, 49, on the second day of her freshman year of high school. “The fact that we could rise above it shows the type of people we are. Al Qaeda and now ISIS, they’re not going to beat us.”

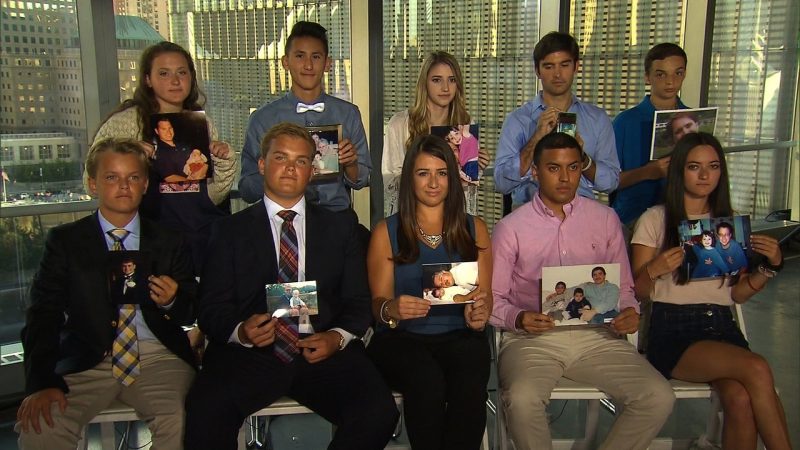

There were 3,051 children under the age of 18 who lost a parent on 9/11. Ten of them — ages 14 to 29 — gathered on the 10th floor of 7 World Trade Center recently to share their stories in a Town Hall with CNN’s Brooke Baldwin. They spoke of their loss and of lessons learned. Of what it has been like to come of age in the age of terror.

All lost their fathers. Five of the 10 have no memory of them. Two — Kevin Hannaford and Rodney Wotton — were born after 9/11. They exude youthful optimism mixed with tremendous maturity. They don’t bear hate. Far from it.

The building that once stood where they’ve gathered collapsed the afternoon of that fateful day, collateral damage from the towers being felled. The new building that has taken its place personifies them — having risen from the ashes, rebuilt after years of hard work, polished and impressive.

The room overlooks the 9/11 Memorial, with its footprint waterfalls and quiet space.

Hallowed ground. Their fathers’ graves.

“A lot of our parents’ bodies weren’t found after 9/11, so that could be literally where our fathers’ bodies lay to this day. It is a memorial, and it is our grave,” says Caroline Tumulty-Ollemar, 15.

When she goes to the site, she finds her father’s name inscribed in the bronze parapet surrounding the memorial pool where the south tower once stood. Lance Richard Tumulty was the football captain of his high school team, a 32-year-old manager for Euro Brokers Inc., who worked on the 84th floor. She reaches out, runs her fingers across the letters.

“I put my hand on his name and talk to him,” she says. “I just like to catch up and let him know how I’m doing, and let him see that what has happened to him hasn’t held me back.”

Sometimes, he reaches back. One night this summer, she looked at her father’s photograph in her room and felt something brush against her shoulder. “Not in a creepy way,” she says, crying, “but in a way that he was there and he was saying, ‘You’re going to be OK.’

“It was just like him putting his hand on my shoulder and saying, ‘I’m so proud of you.'”

They are a tight-knit crew, these 10. Being with each other brings comfort.

Kevin Parks, 29, mentors Rodney Wotton, 14. He takes him to ball games and dinners, and lends support when the pain becomes overwhelming. Rodney is the same age now that Kevin was when he lost his dad.

Born eight days after the attack, Rodney initially resisted emotional support when his mother suggested they seek it out. He was afraid that being around others “would kind of bring back memories of how I didn’t have a dad.”

But then the two met at a gathering of Tuesday’s Children, an organization created to help the children who lost a parent on 9/11. And now, sitting beside Kevin at the Town Hall, Rodney talks of the transformative power of their relationship. “He’s just been the father figure in my life since I never did meet my dad.”

Surprised by the admission, Kevin responds, “It means a lot hearing that. I’ve always said I get more out of the relationship than he does.”

Adds Jessica Waring, “With people who have gone through what you’ve been through, it’s an unspoken thing. You’re instantly friends.”

Some have been confronted by conspiracy theorists. They were told that 9/11 didn’t happen. That the planes didn’t hit the towers.

“I just want to look at them and go, ‘Then, where did my father go?'” says Tumulty-Ollemar. These 10 symbolize resilience. They brush off negativity. Maintain focus. Rebound from the depths of despair.

That’s something 21-year-old Austin Vukosa knows well. He was 6 when his father, Alfred Vukosa, 37, was killed. One of the few memories he recalls is playing catch in the park, his dad snagging the baseball with his bare hands.

In the months after the attacks, he went to his mother with a plan to join his father: He wanted to slit his wrists.

“I was telling my mom I wanted to be in the same place my dad was — just to be with him,” he confides. “Obviously, looking back, it sounds kind of frightening.”

A recent graduate of the University of Notre Dame, he is honoring his father by following in his footsteps. In August, he completed his first month of work at Cantor Fitzgerald, where his father worked as an information technology specialist. Cantor was hit especially hard, losing 658 of its 960 employees on 9/11.

“Just to follow his footsteps at the same company has been a big sense of accomplishment for me,” he says.

Walking through the doors on that first day was “definitely surreal.”

“It drew me a little closer to him.”

To be close to Dad is something they all yearn for.

Jessica Waring’s father was a diehard Green Bay Packers fan . Recently, when she was walking down the street in Manhattan and thinking about him, she looked up to see somebody wearing a Packers jersey. The time on her phone read 9:11. It gave her chills.

That kind of thing happens all the time.

Nicole Pila, 17, often listens to a recording of her father in his final moments. James Gartenberg, a 35-year-old real estate broker in the north tower, spoke with WABC news anchors by phone shortly after the building was hit. He was on the 86th floor on the east side of the building, trapped with one other person. He described the windows blowing out from the inside when the plane struck.

“Debris has fallen around us,” he says. “Part of the core of the building is blown out.

“If I’m on the air, I want to tell anyone who has a loved one in the building, the situation is under control for the moment and the danger has not increased. So, please, all family members take it easy.”

Says Nicole: “In his last moments, he was putting others before himself.” The recording brings him back to her. “It’s the last thing I have left of him.”

Juliette Scauso, 19, is among the few who has an artifact from that day. Dennis Scauso, 46, was one of 343 firefighters killed on 9/11. His crushed helmet was recovered.

And it comes with a remarkable story. Juliette’s mother and other widows of 9/11 had gone to a psychic in February 2002 searching for answers. They were desperate for any sign, any clue of their loved ones. The psychic looked at her and said she could see her husband’s badge number as clear as day.

Juliette’s mother made phone calls and eventually learned, yes, there was an item with Dennis Scauso’s badge number. In the hectic fray of search and recovery, nobody had informed the family of the discovery.

“The helmet is crushed to about this big,” Juliette says, holding her thumb and finger about 2 inches apart. “The entire thing. It’s unrecognizable. But the badge number, which is made out of a sticker, is perfectly intact.”

No other remains of her father were ever recovered. Her mom keeps the helmet wrapped in plastic in her bedroom. “It’s bittersweet because it was something of his — something that was with him during his last moments.”

That feeling of emptiness, of not being able to give their fathers a proper burial, is omnipresent. More than 40%of the 9/11 families never received their loved one’s remains.

For Sal Pepe, a formal goodbye to his namesake came 10 years after the attacks. His father, Salvatore Pepe, 45, worked on the 97th floor of the north tower as an assistant vice president for technology at Marsh & McLennan.

In 2011, his family bought a crate and filled it with letters, photographs and other special keepsakes for burial. They wrote messages on white balloons and released them at the ceremony. His mother had a hard time letting go of her balloon.

Sal was 11 at the time. The young boy told his mother it was OK to let go — that his father would always be with them. He kept himself from crying that day “to be strong for my mom.”

“I’m dedicating most of my life to making him proud,” says Sal, now 16.

These children grew up too fast. Love your friends and family now, they advise — and don’t be shy about telling them so. Because life can end in a nanosecond.

Kevin Parks ran his first Boston Marathon in 2013. He finished the race and was celebrating with friends and family at a rooftop bar when the bombs went off. The friend next to him was the same guy who was next to him in math class on 9/11.

“It was weird, almost déjà vu,” Kevin says. “The unfortunate part is tragedies of different magnitudes happen all the time. I think the easy default emotion is anger and frustration, and that’s natural. I’d prefer people react with a more positive tone … to figure out a way to make the most of a terrible situation.”

Patrick and Kevin Hannaford honor their dad by helping others. With their mother, they formed the Kevin J. Hannaford Sr. Foundation, a charity that helps pay the tuition of children who have lost a parent in their hometown of Basking Ridge, New Jersey.

The charity’s main fundraising event has always been blessed with perfect weather. The running family joke, they say, is that it’s their dad’s “signature on the day.”

“We feel him a lot that day,” Patrick says.

Patrick was 2 on 9/11 and was thrust into the role of consoling his pregnant mom and helping to raise his brother Kevin, born four months later.

“He stepped up to be my dad,” Kevin says.

With their short-cropped blond hair and bright smiles, they are spitting images of their father. One photograph of their dad in swim trunks as a boy looks so much like the young Kevin that when people see it, they say, “That’s a great photograph of you.”

“It’s actually my dad,” he responds.

“It makes me feel good,” he says. With a big grin, he notes his father was handsome, “so hopefully I can be the same way when I’m older.”

This group knows loss, undoubtedly. They also know love.

If they could ask their fathers one last question, what would it be?

Nicole Pila immediately pipes up: “Are you proud of me?”

“I would say the same thing,” adds Austin Vukosa. “I would want to know if he’s proud.”

Jessica Waring: “Yeah, I think I’d want to know the same thing, too.”

Patrick Hannaford pauses. “I don’t know. There’s a lot to ask, so I’m not sure what I’d pick.”

His younger brother, Kevin, says he’d ask, “How are you?”

“I’ve never met him. There would be a lot. I could write a book.”

Caroline Tumulty-Ollemar says she’d want to know “if he was satisfied with the time he got here.”

“I think I’d want to know,” says Sal Pepe, “if he had a funny memory or a funny story that he could share.”

Juliette Scauso: “I would ask if he was proud of not only me, but who my family has grown into without him there.”

“I’d ask him to tell me some of the stories I was too young to know back then,” says Kevin Parks.

The last one to reveal his question is Rodney Wotton. “I would ask if there were ways to remember him more, like if he’s proud of the way we’re keeping him in our life.”

These children will never forget.

And they don’t want the world to forget either.