From the time he was big enough to climb onto the back of his dad’s Harley, Jake Carrizal felt the pull of the open road.

The summer he was 9, he rode on the back of his dad’s bike to Mount Rushmore and then on to Sturgis, the annual Super Bowl of biker rallies, in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

“He was on the back holding on tight. People would point and say ‘Oh, look how cute!'” recalled his dad, Chris Carrizal.

Along the way, Jake got his first look at the biggest, baddest bikers in all of Texas, the Bandidos: “Just seeing them riding down the road,” Jake said, “you knew: You don’t mess with these guys.”

Jake and his dad both became Bandidos. Chris Carrizal earned his patch in 2005, and Jake, 34 and a father of two, joined seven years later. He rose quickly to become vice president of the Dallas chapter, second in command to his uncle.

Jake was at a barbecue at his uncle’s when he got his Bandidos patch — a “fat Mexican,” they call it: a round-bellied, grinning caricature with a handlebar mustache and sombrero, wielding a pistol in one hand and a machete in the other (bikers are not known for political correctness). Jake was so moved he cried that night as he stitched the patch onto his jacket under the glow of a flashlight in the backyard.

“There’s a brotherhood, you know,” he said, explaining why he chose the life of a Bandidos biker. “It’s a good group of guys, and we like to do a lot of the same things — ride motorcycles and have fun.”

It’s been a year since Jake and his dad last rode together as Bandidos. May 17, 2015. Destination: Waco.

They were supposed to attend a regular meeting of a statewide umbrella organization called the Confederation of Clubs. The location was Twin Peaks, a biker-friendly, Hooters-style restaurant where cold beer is served by women in skimpy cutoff shorts.

When the first Bandidos arrived from the Dallas chapter, they found about 60 members of a smaller biker club — the Cossacks — waiting. The Cossacks aren’t confederation members, and as far as the Bandidos from Dallas were concerned, they hadn’t been invited.

Accounts vary over what got the fists — and the bullets — flying on a Sunday afternoon that would mark the most violent day in Texas biker history. Police suspected something was up; they’d installed cameras and stationed about 20 cops around the parking lot. But they stood back, keeping a low profile.

Was the beef over what patches the Cossacks could wear, as police had theorized? Did somebody at Twin Peaks run over a Cossack prospect’s foot, as some witnesses suggest? Was it over who owed dues to whom? Or was it just a dumb beef about parking spots?

Words were exchanged at first, then pushes, and then punches. Witnesses said somebody fired three shots. Other people pulled guns and all hell broke loose. It lasted less than two minutes and when it was over, nine bikers had been fatally shot and 18 were wounded, including Chris, who took a bullet in the shoulder.

Jake said he had been backing his midnight blue Harley into a parking space when the brawl blew up around him. Father and son lost each other in the confusion, and for a time each believed the other had been killed.

Nearly a year after the deadly melee, the Carrizals and half a dozen other bikers — both Bandidos and Cossacks — are speaking out. They agreed to appear on camera and talk for the first time about their clubs, their culture and the events in Waco. Bandidos leader Jeff Pike, known as “El Presidente,” also broke his long silence. He said he likes things quiet and never had a reason to speak out before Waco.

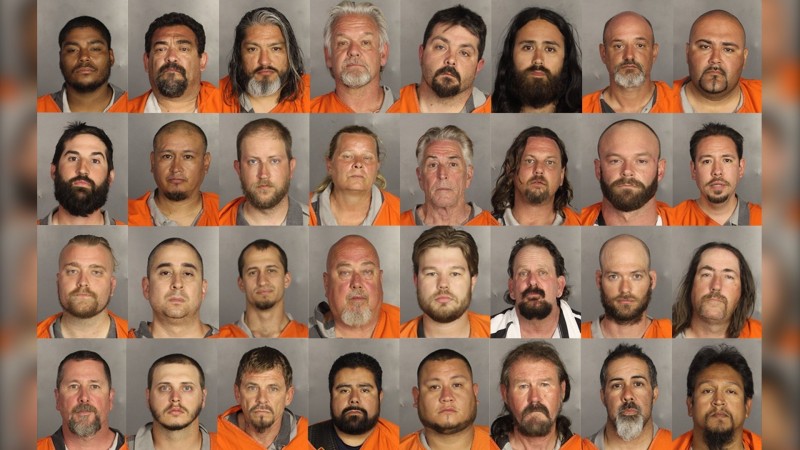

After 177 bikers were arrested, bail initially was set at $1 million each. Jake spent 23 days behind bars before his bail was lowered enough that he could post bond. He sold one of his bikes to come up with the required 10% in cash.

A local grand jury later indicted 154 bikers — including the Carrizals — on a single, generic count of engaging in organized criminal activity. A conviction carries a stiff penalty: from five years to life in prison. But nobody seems to be able to pin down the specific crimes alleged, or to even get a trial date. Local officials aren’t talking.

The bikers say they’re eager for the chance to defend themselves. They say the man who fired the first shots is dead and everyone else was acting in self-defense. Both Cossacks and Bandidos see themselves as crime victims.

But this wasn’t just a matter for the local police. The feds had been building a case against the Bandidos unrelated to the Waco shootout and showed their hand in January, when an indictment was unsealed in San Antonio. It names three Bandidos leaders, including Pike, as masterminds of a racketeering conspiracy and methamphetamine distribution ring. The indictment alleges the club masks a criminal empire that rules through extortion, intimidation and murder. All three have pleaded not guilty.

The feds allege they found “a closed society” in which loyalty “to this organization and their fellow brothers is valued above all else.” Bandidos, according to the indictment, “do not fear authority and have a complete disdain for the rules of society.”

‘People our parents warned us about’

Bandidos refer to nonbikers as “polite society” and the club motto says it all: “We are the people our parents warned us about.”

They are in the biker big leagues, one of four major motorcycle clubs. The other three are the Hells Angels, the Pagans and the Outlaws. Members of those clubs as well as some others are known as “outlaw bikers” or “one-percenters.”

Make no mistake: To Bandidos, the label “outlaw biker” is a point of pride. To be a one-percenter means the rules for 99% of the riders on the road don’t apply to you.

“To us it’s a family thing, it’s not a criminal organization,” Chris Carrizal said. “We love each other and we love to ride and we’re proud to wear that fat Mexican on our back. For people who don’t understand, being in the Bandidos means you’ve reached the top, you’re like the CEO.”

To both father and son, being a one-percenter is a commitment.

“I’m a Bandido 24/7,” Chris said. “I’m not a poser. I’m not a yuppie, a wannabe. I live the life of a professional motorcyclist. I am a one-percenter.”

Until Waco, the Bandidos didn’t take the Cossacks seriously. At best, they were “an aspirational club,” in the words of Donald Charles Davis, a Vietnam vet, biker and former newspaper reporter who writes The Aging Rebel, a blog followed religiously by bikers. He’s working on a book about the Waco shootout.

The Cossacks motto: “We take care of our own.”

“We’re working guys, man, and that’s the whole problem,” said Owen Reeves, a national Cossacks leader. “We’re working guys, and if you try to take something from a working guy, then you’re gonna have hell doing it.

“You know, them guys, they wanna control everything and make you pay this, pay that, and we’re not gonna do it,” he said of the Bandidos. “We’re grown men, and last time I checked, we live in America.”

Both the Bandidos and the Cossacks were founded in Texas during the 1960s — the Bandidos in 1966 in Houston and the Cossacks three years later in Tyler, in east Texas. There has never been any love lost between them.

At the time the two clubs started, disillusioned Vietnam veterans were returning from an unpopular war to an unwelcoming society. They no longer fit in at home and felt most comfortable in a structured hierarchy of men with the shared experiences of war, their brothers in arms. Motorcycle clubs offered that sense of camaraderie, Davis said.

The Cossacks might have been ambitious, he added, but before Waco the Bandidos viewed them as little more than a nuisance.

“They’re in their own little world. I have no respect for them,” said Chris Carrizal. Sprinkling his speech with F-bombs, he added that Cossacks “have no idea what it’s like to be a one-percenter or what it is to be in a real club.”

As for what happened at Waco, he said, “they showed their true colors that day.”

Most people learned about outlaw bikers through popular culture. The two best examples are “The Wild One,” the 1953 movie starring Marlon Brando, and gonzo writer Hunter S. Thompson’s 1966 account of the time he spent with the Oakland, California, chapter of the Hell’s Angels.

More recently, Kurt Sutter’s FX series, “Sons of Anarchy,” romanticized the biker life, although Davis and other bikers say it took some poetic license.

Although motorcycle clubs now can be found around the world, there’s something uniquely American about the one-percenters who live outside the restrictions imposed by “polite society.” They live by their own rules, which as any biker will tell you, might make them outlaws, but doesn’t mean they’re criminals.

Davis compares them to the cowboys who won the West, sprinkling his anecdotes with classical literary and cultural references.

“The motorcycle outlaw world is the last manifestation of the American frontier,” he said.

They are bad boys, and who doesn’t like a colorful bad boy?

‘Big dogs and little dogs’

Cops and federal agents might view outlaw bikers as criminals, said Davis, but he understands the draw the outlaw biker holds for others in 2016. He sees it as a response to the discontent and perceived unfairness that recently hung like a pall over American society. He compares the renewed interest in outlaw biker clubs to the rise of the tea party and Occupy Wall Street, movements that themselves now seem dated.

Davis hasn’t just studied everything academics have to say about biker clubs. His education also comes from the streets. He used to belong to a club but won’t say which one, except that today it would be considered a “one-percent” club.

Besides ongoing conversations with bikers from around the world, he reads everything he can get his hands on, from court documents to doctoral dissertations.

“Bikers are predominantly libertarian,” he said. They aren’t much different from men who, in another era, “needed elbow room from society and so they ran off to Kentucky, to Texas, to California, to Alaska. …”

It’s a cultural note that resonates in the Lone Star State. Texans are famously fond of cowboys, and they can’t resist an outlaw with a good mustache and some panache.

Terry Katz, a Baltimore-based state police investigator, has been following biker gangs since the 1980s. Katz is vice president of a 600-member group called the International Outlaw Motorcycle Gang Investigators Association.

He said the Bandidos, being the dominant club, saw little choice but to stand up to a challenge from the Cossacks.

“These guys aren’t going to put up with anybody disrespecting them,” Katz said. As bikers see it, Waco shows “they were just taking care of business.”

Davis agreed that Waco was all about respect. The club on top demanded it, and the ambitious challengers grew weary of bowing down.

“At the end of the day, the Bandidos are the big dogs,” said Katz, “and you can’t stay a big dog if you let a little dog intimidate you.”

Regardless of what started the gunfight at Waco — whether it was over a patch or a parking space — it’s “irrelevant to everybody else,” Katz said. But respect matters to a biker. Respect for your club is worth dying for.

“These guys are not going to put up with anybody disrespecting them,” Katz said. “If you put nitro and glycerin together, eventually you’re going to have an explosion.”

Could the bad blood and resulting violence really have been over a patch, as police said?

In addition to wearing the “fat Mexican,” the Bandidos and some of their support clubs — smaller biker groups loyal to the dominant club — also sport what’s known as a “Texas bottom rocker.” It’s a curved patch sewn onto the lower back of a biker’s vest that announces his territory. Bandidos also ask their support clubs to wear the round Bandidos “support cookie” patch.

Cossacks started wearing the large Texas bottom rocker panel on the back of their vests in 2013, according to the indictment. They didn’t ask anyone for permission.

The Bandidos responded by letting everyone, even their smallest support clubs, wear the Texas rocker, diluting its prestige, Jake and other members said. Bandidos president Pike said the Cossacks even thanked them on social media.

But the dispute over the Texas rocker brought up another sticking point. The support clubs pay dues of $50 a month, but the Cossacks were refusing to pay for what one Cossack described to CNN as “the privilege of riding my motorcycle in Texas.”

Reeves, the national Cossacks leader, acknowledged to police that “there’s a lot of residual hatred” that “needs to be over.” Cossacks were tired of being hassled over wearing the Texas rocker patch. That simple fact, he added, accounted for “80%” of their issues with the Bandidos.

“We’re a motorcycle club. We want to be left alone. We just want to ride, and to ride in Texas,” said another Cossack who spoke with CNN under a pseudonym, “Dean.”

Paying dues to someone else is an obvious irritant, said Dean, who was at Waco: “Why am I going to pay dues if I’m a part of myself? It doesn’t make sense why I’m going to pay someone to be able to ride my motorcycle in the state of Texas.”

Pike said all this Cossacks resentment is a recent development.

“We talked about it and said ‘Where did this hatred come from?’ It just popped up,” the Bandidos president said. “Those guys have been around as long as we have almost, and we never hung out together or anything, but we never bothered each other, either. And in the past two years, it’s just gone crazy.”

‘We are at war’

There are almost as many versions of what caused the tension between the Bandidos and Cossacks as there are Bandidos and Cossacks. But the federal indictment is as good a place as any to start. It lays out a series of skirmishes between the clubs during the months leading up to Waco.

Pike and the other two Bandidos leaders named in the indictment were nowhere near Waco on the day of the shootout. (All three have pleaded not guilty.) And, indeed, it makes no mention of Waco. But it does provide a brief, official version of the bad blood building between the two clubs.

The Bandidos are a huge, international club with 175 chapters — 42 of them in Texas.

The Cossacks also are a Texas club, and much smaller, with maybe 200 members across the state. But they are ambitious. They’d been on a recruiting spree, and as 2015 began, they were standing up to the Bandidos again.

By February 2015, Pike was stepping aside as national president of the Bandidos and taking a health leave.

Pike handed responsibility over to his number two, vice president John Xavier Portillo. It was Portillo who informed club members that they were at war with the Cossacks, according to the indictment.

The first clash came in November 2013, when 10 Bandidos confronted a group of Cossacks in Abilene. A knife fight broke out, and four Cossacks were seriously hurt. “This is our town. If you come back, I will kill you,” the president of the Bandidos’ Abilene chapter allegedly warned, according to the indictment, which didn’t name him.

About a year later, Portillo again told club members about the ongoing war. A group of Bandidos crashed a sports bar during a meeting between the Cossacks and their support clubs. A member of a support club called the Ghost Riders was shot and killed. As they left, the Bandidos slapped one of their club stickers on the bar door.

In March 2015, the indictment states, Portillo told Pike to “turn his back from what I’m gonna do” in what prosecutors claim was an attempt “to shield Pike from criminal responsibility” regarding the war with the Cossacks. He allegedly repeated on March 3 that the Bandidos were “at war” with the Cossacks, stating that he “wants that Texas rocker back,” referring to the patch.

Later, on March 20 and 21, the Bandidos went on a “birthday run” to celebrate the anniversary of their Tyler, Texas, chapter. Tyler, of course, was the birthplace of the Cossacks. Portillo, according to the indictment, urged four Bandidos to “shake up (expletive)” and “get a little aggressive” with the Cossacks.

Then, on March 22, about 20 Bandidos swarmed a Cossack pumping gas in Palo Pinto County. They demanded his vest, which included the Texas rocker, and beat him with a claw hammer, according to the indictment.

On May 1, the Texas Joint Crime Information Center issued a bulletin warning of “escalating conflict” between the Bandidos and Cossacks. It listed additional confrontations — including a March 22 assault of a lone Cossack by about 10 Bandidos in Lorena, a plan in which 100 Bandidos would ride to Odessa on April 11 to start a “war” with the Cossacks, and reports of three confrontations between Bandidos and Cossacks in east Texas on April 24.

As the bulletin stated: “This conflict may stem from Cossacks members refusing to pay the Bandidos dues for operating in Texas and for claiming Texas as their territory by wearing the Texas bottom rocker on their vests.”

‘Cossacks all over me’

The Cossacks said they came to Twin Peaks to talk about a truce. The Bandidos say they rolled up on an ambush.

By noon, about 60 or 70 Cossacks had already lined up their bikes in the best parking spots at Twin Peaks. They had the run of the patio, too, when Jake and the others from Dallas pulled up.

The Bandidos had wanted to get there early to stake out a good table. They said they hadn’t counted on seeing any Cossacks there.

Jake spotted an empty section along the row of parked bikes and started to back his Harley into the spot on the end.

“As I’m backing in, I see that whole patio where the Cossacks were — they all cleared out and came to the parking lot,” he said. He spotted batons, brass knuckles and clubs and immediately knew: “They weren’t there to chit-chat. They were on a mission. They were there to confront us.”

He was surrounded. That saying about your whole life flashing before your eyes? It’s true, Jake said.

“All I can think about was my kids, and my girlfriend, and my whole life, you know? And just seeing them with brass knuckles. Who does that, you know?”

When he saw the first punch thrown, he knew it was on.

“They were attacking us. And I was fighting for my life,” he recalled.

“I had guys all over me — Cossacks all over me,” Jake said.

The Bandidos behind Jake didn’t have time to shut off their bikes before the Cossacks were all over them, too, Jake and his father said.

“One of these punks, he comes out shooting like Rambo,” Chris Carrizal said. “It was planned out, man, it was planned. They were waiting for us. They were waiting to kill as many of us as possible. There’s no doubt in my mind. We weren’t there to murder anybody, we weren’t there to hurt anybody.”

Lying on the ground, Jake pulled one of his assailants close, using him as a shield.

“And the whole time, I’m hearing gunshots go off. I hear the shots going off, whizzing by me. And you know, my dad’s there, my uncle’s there, I’m there and my brothers are there,” Jake said. “If I’m not getting hit, someone’s getting hit.”

And it’s just a bad feeling. Horrible feeling. Scary feeling. “I’ve never been that scared in my life.”

Somebody pulled the people off Jake, and he crawled under a truck for cover. He saw a biker lying on the ground and wondered, Was it Dad?

“That’s when it hit me,” Jake said. “(The biker) wasn’t moving, he was laying on his back, and without a doubt he was killed. It was hard to see. It was hard to comprehend, and I remember yelling for my dad, because I knew he was somewhere there.”

Then he saw his father appear around a corner, helped along by two police officers. He was a bloody mess, but he was walking.

“That was an awesome feeling,” Jake said. “He got shot in the back, in the shoulder, and as bad as that image was seeing my dad full of blood, it was awesome seeing him, knowing that he was alive.”

Chris Carrizal had wondered if he was a goner at 52.

“When I first fell and hit the ground, I could feel the blood coming out of my shoulder, and I was thinking, ‘That’s it. That’s it, you know, I’m going to die right here today and there’s nothing I can do about it,'” he recalled.

He thought he’d seen his son’s body, too. The dead biker he spotted wore square-toed boots, just like Jake does.

“I said, ‘Man, Jake’s dead, he’s laying there dead. …'” His voiced trailed off as he fought back tears. “It was tough, man, but luckily it wasn’t him.”

Someone brought Chris to Jake. He laid his dad down on a grassy strip by the parking lot, resting his father’s head on his lap.

“He was on blood thinners,” Jake recalled, “and he was telling me, ‘You take care of the boys, and you take care of Mom.'” Jake didn’t want to hear that. He urged his father, “Be strong, you’ll make it.”

Only later would he find out how lucky his dad had been. A few millimeters to the left and the bullet would have killed him. A little to the right, and he would have been paralyzed.

Ambush or not, the simple truth is the Cossacks got the worst of it. When the guns finally fell silent, seven Cossacks lay dead — guys with road names like Rattle Can, Side Track, Diesel, Trainer, Chain, Bear and Dog. Just one of the Bandidos — “Candyman” — was killed, along with an unaffiliated biker, a 65-year-old Vietnam vet with Bandidos friends.

Afterward, police recovered more than 470 weapons, including 151 firearms.

Operation Texas Rocker

The feds came for El Presidente before dawn on the first Wednesday in January. Nearly eight months had passed since the fight in Waco, but Bandidos leader Pike hadn’t been there for that. He was waking up after colon surgery when his wife told him about the shootout with the Cossacks. Through the haze, it seemed surreal.

Still does.

Pike might not have been at Twin Peaks, but the feds see him as the shot-caller, which is why they’d come calling. They had an indictment naming Pike as the head of a 2,000-member gang that murders and beats rivals, deals methamphetamine, engages in extortion, wages war with its enemies and terrorizes witnesses.

Pike is confident the government will be unable to directly link him to illegal activity. The indictment does not accuse Pike of specific crimes; instead, it places him at the top of the Bandidos and alleges he benefited from the crimes of others.

In announcing the indictment hours after Pike’s arrest, the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Joseph M. Arabit said their investigation — dubbed “Operation Texas Rocker” — had “inflicted a debilitating blow to the leadership hierarchy and violent perpetrators of the Bandidos Outlaw Motorcycle Gang.”

“This 23-month operation highlights a deliberate and strategic effort to cut off and shut down the supply of methamphetamine trafficked by the Bandidos as well as other related criminal activity,” said Arabit, who heads the DEA’s Houston office.

On that early morning in January, armed agents quietly circled Pike’s house, set on five acres in Conroe, a straight 45-mile shot north of Houston on I-45. Over a loudspeaker, they ordered Pike to surrender.

Nobody was more surprised to see that SWAT team than Pike, who at age 60 has been with the Bandidos for 36 years and presidente for the last 11. He’d been investigated a few times before but never arrested, which made him a standout among Bandidos leaders.

His four predecessors had all gone to prison for various acts of mayhem. Bandidos founder Donald Chambers and two others were convicted of murder for killing two drug dealers after making them dig their own graves.

Pike said he likes things quiet. He insisted he’s boring. He staggered sleepily out of the house in bare feet, his hands in the air. He recognized one of the agents.

And then he saw the armored vehicle. He knew this was serious.

“There’s an Army tank-looking thing with red and blue lights on it in my driveway,” he said. “But they said, ‘Come on out, keep your hands up.’ And I walked out, and it was very cordial.”

He said he’s grateful agents didn’t trash his house. “They didn’t wreck my gate, they didn’t even drive on the grass. I made sure my dog didn’t get out. I was very appreciative of the way they arrested me.”

And then he read the indictment and didn’t see anything to worry about.

“There’s nothing in that indictment that says I did anything,” he said. “But the cops got an old saying: ‘You might beat the rap, but you’re not going to beat the ride.’ So I’m just going to have to play along here for a while.”

He said the feds have 800 hours of taped conversations. He is like a ghost in them, he said, except for a brief mention in a single phone call. If he’s a shot-caller, he appears to be a very well-insulated one.

“Somebody mentioned my name in a telephone call,” Pike said. “That’s why I got arrested. I mean that’s ridiculous.”

He wonders aloud what the point of all this might be. What do the feds want?

“Are they out to just destroy us, or do you want to make good citizens out of us?”

Like the local police, the feds aren’t talking. Legal observers expect more federal indictments to come, naming more Bandidos as participants in the alleged conspiracy. Waco could prove to be fertile ground, supplying future federal witnesses — and defendants.

There are also signs that federal investigators’ interest expanded after Waco to include the Cossacks. They seem to have caught the eye of the DEA, in particular, according to an internal memo obtained by CNN.

“I don’t think they’re gonna try anybody in Waco,” said Houston lawyer Paul Looney, who represents an arrested Cossack and a couple caught up in the melee.

“I think the entire detention in Waco is a babysitting exercise while the feds complete their investigation. There’ll be a superseding federal indictment out of San Antonio in which a lot of the people that were arrested in Waco go into that indictment, and the Waco prosecutions will just go by the by.”

‘He had a real fighting heart’

A year later, Bandidos and Cossacks look back on Waco and shake their heads at the violence they witnessed. Nearly everyone says it caught them by surprise. Some of the older guys say it reminded them of combat. Many still struggle with having been forced to leave bleeding “brothers” behind.

Reeves, the Cossacks leader, was shot — and so was his son.

“I was on the ground,” he told police, according to his statement, which CNN obtained. “I can’t see anybody pull the trigger but I heard a s— ton of bullets flying. It was pop-pop, nonstop. And I didn’t wanna get up. I didn’t even wanna turn my head and see where it was coming from. I was trying to be still so they didn’t pop me, thinking I was still alive. Being honest man, I, I was f—ing scared.”

When the shooting stopped, Reeves said, he looked up and saw a fellow biker “with a hole in his head.” And then he saw his son, dying.

“He got clipped in the head. My son got shot in the head, and started bleeding out next to me. And I started trying to deal with him,” Reeves told police. “The other guys were trying to resuscitate him, and he had a real fighting heart, but (police) made us leave, and he just got left.”

Another Cossack said he, too, was troubled by the wounded bikers left behind in the mayhem. He believes more might have survived if they’d received prompt medical attention.

“Would I take a bullet for a brother? I have, even though I was unarmed. I was there,” said Dean, the Cossack who spoke with CNN on the condition his identity not be revealed.

“I still remember the blood coming out of me, the pain, the people around me being shot,” Dean said. “It just seems like it happened so fast, but it took forever for it to end.”

He said nobody meant for Waco to happen, and he struggles to understand why it did.

He’s asked the question that has been on everyone’s mind: What did all those people die for?

“It almost looks like stupidity,” he said, pausing and searching for a better reason. He seems relieved when one comes to mind.

“They died protecting other people,” Dean said. “They were the ones who took the hits. They were the ones who stopped the bullets from hitting other people.”

It sounds so much more noble.

Because, as the Cossacks and Bandidos kept telling us, dying over a patch would be stupid.