The man convicted of murdering a child in one of the nation’s oldest cold cases will have to wait to learn whether his guilty verdict will be tossed out — despite a prosecutor’s stunning conclusion that he is innocent.

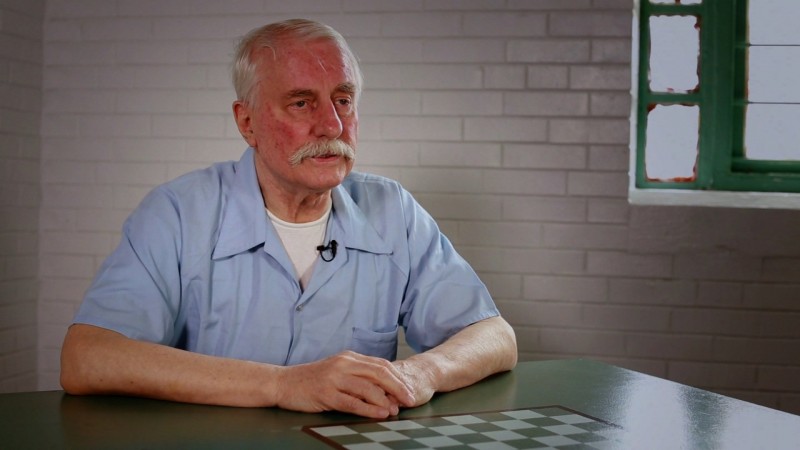

Jack McCullough, a military veteran and former police officer, was clearly frustrated Tuesday as his court hearing focused on issues of procedure rather than his innocence or guilt. He was told he’d be appointed a private attorney and would have to return to court on April 15 to schedule future hearings.

McCullough seemed deeply disappointed that he would not be walking out of the courtroom a free man.

“I’ve been in prison, locked up now for almost five years,” he told Judge William Brady, his voice quaking with frustration. “I’m innocent, and I can prove I’m innocent. There has to be an end to this somewhere.”

He wasn’t the only person touched by this cold case — believed to be the nation’s oldest to go to trial — who vented frustration on Tuesday.

Charles Ridulph, who was 11 when his little sister Maria was kidnapped and murdered, said he believes his family has been abandoned by the legal system as attention shifts from the victim to the convicted killer and his appeals.

Ridulph, now 70, has filed a petition seeking a special prosecutor to defend the guilty verdict and said he plans to hire an attorney to protect his family’s interests.

The judge explained that the situation was unusual and it would take time to figure out how to proceed.

“I’m not a seer, I cannot tell you with any certainty how long it will take,” Brady said. “I have a process to follow and part of that process is to make sure your rights are protected as well as everybody else’s.”

He was addressing Ridulph at the time, but his words apply to McCullough as well: “You have a right to file what you want to file, you have the right to be heard. But that doesn’t mean you’re going to get the relief that you are seeking. The process will determine what the end result is.”

Ridulph was accompanied in court by a sister, Pat Quinn, as well one of McCullough’s sisters, Mary Hunt. The defendant was 17 and known as John Tessier when Maria Ridulph, age 7, was snatched from a street corner in Sycamore, Illinois, on December 3, 1957. The Ridulph and Tessier families lived within a couple of blocks of each other then.

“This is horrible,” said Hunt, who embraced Ridulph and Quinn as she walked into the courtroom. All three had come to support the guilty verdict they said had given them peace and a sense of closure.

“I have no doubt in my mind that everything will turn out OK,” Hunt told reporters on the courthouse steps. “I was the one that lived with this monster.”

But McCullough’s stepdaughter, Janey O’Connor, says he’s no monster. She had driven from Seattle, Washington, to Sycamore to support the man she has considered her father since she was 14.

They made eye contact and smiled as McCullough was led into court in shackles. As he was escorted out — and back to prison — she cried out, “Jack! Jack!” to catch his attention. The two again exchanged quick waves.

McCullough, 76, seemed in good health and wore heavy black eyeglasses; a cellmate had stabbed him in the eye a few years ago as he slept. His white hair and goatee were neatly trimmed. O’Connor has often said her worst fear is that he dies in prison, convicted of a crime he says he did not commit.

McCullough has always insisted he is innocent of Maria’s abduction and murder. He was questioned and cleared by the FBI in 1957 after claiming an alibi that placed him some 40 miles from the crime scene.

He received support last week from an unexpected corner: Richard Schmack, the state’s attorney for DeKalb County, Illinois, filed court papers stating unequivocally that McCullough was innocent and had been wrongly convicted. His arrest and conviction were based on “false and misleading” statements, Schmack found.

“Defendant’s involvement in Maria’s disappearance and murder is a physical impossibility unless every witness statement gathered from family and neighbors is completely wrong,” Schmack concluded.

The prosecutor filed a lengthy report with the court detailing what he said were flaws in the evidence against McCullough. No physical evidence ties McCullough to the crime, and the prosecutor said police and prosecutors used a faulty time line in piecing together the case against him.

Maria was playing with a friend in the snow when a young man who called himself “Johnny” approached the girls and offered Maria a piggyback ride. She and Johnny vanished after the other child, Kathy Sigman, ran home to fetch her mittens.

Despite an investigation that was followed closely by FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover and President Dwight Eisenhower, Maria’s murder went unsolved for more than half a century.

Illinois State Police revived the investigation after receiving a tip from another of McCullough’s sisters, Janet Tessier. She emailed a tip line saying her mother had revealed on her deathbed in 1994 that “John did it,” meaning the murder of Maria Ridulph. Janet Tessier, who lives out of state, was not in court on Tuesday.

McCullough was arrested in Seattle, Washington, in 2011 and convicted the following year in Sycamore of kidnapping and murdering the child. He had nearly exhausted his appeals but filed a last-ditch, handwritten petition asking a judge to review his case and declare him innocent. That effort failed, but it caught the attention of his former public defender, Tom McCulloch, who said he saw merit in some of the arguments and filed a formal motion asking the judge to reconsider.

Schmack was asked to respond and dropped a bombshell with his lengthy report lambasting the police and prosecutors.

On Monday, the victim’s brother began pushing back by filing his petition for a special prosecutor.

“My sister Maria was snatched away … and murdered, abandoned in the woods,” Ridulph wrote. “And now, Richard Schmack has abandoned her yet again, and he has done so for the wrong reasons.”

Ridulph is asking the judge to consider his request at the April 15 hearing.

Schmack said he was ethically compelled to reinvestigate the case and announce his findings. He declined to comment on Ridulph’s criticism, except to note that it would be highly unusual for a judge to appoint a special prosecutor simply because a victim’s family was unhappy with decisions in a case. To do so, he said, would shut down the legal system.

Schmack took a close look at the time line of events surrounding Maria Ridulph’s disappearance and concluded it was impossible for McCullough to have snatched and killed the child because he was some 40 miles away in Rockford, trying to enlist in the U.S. Air Force.

Back in 1957, the FBI concluded that Maria was taken from the street corner after 6:30 p.m., but the more recent Illinois State Police investigation moved the time of the child’s abduction closer to 6 p.m.

After reviewing thousand of pages of vintage police and FBI reports, Schmack says Maria likely was taken between 6:45 an 6:55 p.m.

Schmack said he found no evidence to support the theory of an earlier abduction. He points to other indicators of the time, including two witnesses who stated they were watching “Cheyenne” and “Name That Tune” — shows that began at 6:30 p.m.

In addition, two neighbors reported hearing a scream at around 7 p.m.

Schmack subpoenaed records from AT&T and confirmed that a collect call was placed to the Tessier home in Sycamore from a payphone inside the Rockford Post Office at 6:57 p.m. That detail verified McCullough’s alibi, along with two military recruiters who recalled speaking with him between 7:15 and 7:30 p.m.

The details are contained in police and FBI reports from 1957 and 1958 — records that were ruled inadmissible by Judge James Hallock, who tried the case without a jury. In Illinois, police reports are regarded as inadmissible hearsay and can’t be used in place of an actual witness.

But, the appeals court noted, the documents could have been admitted under an “ancient documents” exception to the hearsay rules because they are more than 20 years old. The appeals court said the judge erred, but it did not reverse McCullough’s conviction.

The case was brought by Schmack’s predecessor, Clay Campbell, and there is no love lost between the two. Schmack narrowly defeated Campbell in an election held just a few weeks after McCullough was convicted.

Schmack was unsparing in his criticism of the way Campbell and state police investigators handled the case, going so far as to say they withheld evidence that didn’t suit their time line from judges and grand juries to arrest and convict McCullough.

Ridulph took exception to Schmack’s use of FBI and police reports that had been barred from the trial to exonerate the man he believes is his sister’s killer. He said the prosecutor was acting more like a defense attorney.

“Whatever his motives, Richard Schmack is on a crusade to free Jack McCullough,” Ridulph wrote in his motion. “To allow him to do this goes against everything we as human beings should expect from one another.”

But others coming to court Tuesday hold the opposite opinion.

O’Connor, McCullough’s stepdaughter, said she considers Schmack’s actions to be courageous.

Some in Sycamore have accused the prosecutor of playing politics with the case to bolster his campaign for re-election. But Schmack says pushing to overturn a guilty verdict could be considered career suicide for a prosecutor.

“I really had no choice but to file something,” he told CNN before the hearing.

“If I lose an election because I had some part in freeing someone from prison for a crime they did not commit, that’s fine with me. The fact that it’s taken me three years to do that might be a reason for people to say I should’ve acted faster, and I won’t necessarily disagree with them.”