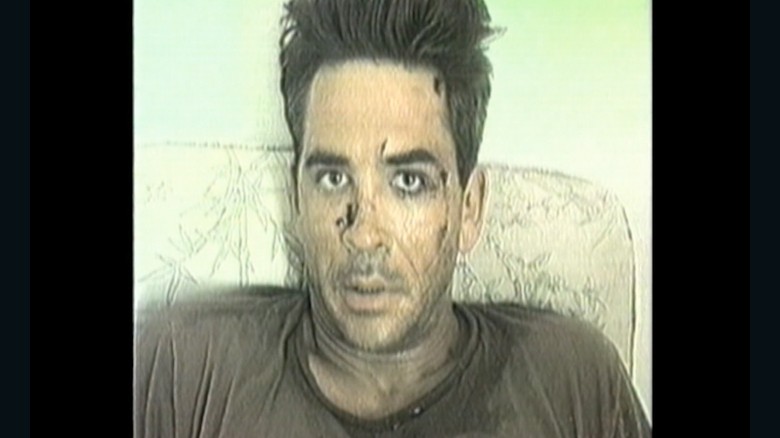

“I can hear them coming … they are on their way and they are going to kill me.”

Sitting in the cockpit of his downed Black Hawk helicopter, Chief Warrant Officer Mike Durant looked to the sky and tried to come to terms with his imminent death.

With each passing moment, his fear built until the crowd descended on him, ripping off his gear and beating him mercilessly.

They broke his nose, eye socket and cheekbone, and Durant was certain they were going to beat him to death.

But just when his chances for survival seemed bleakest, he heard it.

Pop. Pop. Pop.

The sound of gunfire rang out from somewhere in the crowd, and the beating stopped. At that instant, a man emerged from the mass of Somalis surrounding the battered pilot and proclaimed that he would be taken prisoner.

“That’s the turning point where I went from being another American fatality to (realizing) they wanted to keep me alive and brought me into captivity,” Durant said.

Fast-forward nearly 25 years, and Durant, now 54 years old, stands in the kitchen of his Huntsville, Alabama, home, quietly flipping pancakes with his wife, Lisa. The youngest of his six children, Michael, 11, sits at a table, waiting to eat breakfast before school.

During the day, you can usually find Durant at the office of Pinnacle Solutions, the company he owns and operates that specializes in building military training simulators.

Three to four times a week, he heads to Huntsville’s Municipal Ice Complex after work to lace up his skates and play hockey on an organized team.

At first glance, there is little to suggest that the Durants are any different from most American families. Family photos and sports memorabilia line the walls in their home. Michael, dubbed by his siblings as the “Golden Child,” plays hockey, like his father, and hates to be late for school.

But if you look closely at the personal effects that fill a glass case in the living room, there are three medals, lying side by side on the bottom row.

Purple Heart.

Distinguished Flying Cross.

Distinguished Service Medal.

The subtle way that these prestigious military awards are displayed in his home is perhaps a reflection of Durant’s self-image today.

While he fully embraces his experience in Somalia as a pivotal part of his journey through life, Durant admits that he wants people to see him as more than just “the ‘Black Hawk Down’ guy.”

If given the choice, Durant would prefer not to talk about being shot down and held captive for 11 days. But he said he has an obligation to tell his story and share his unique perspective.

‘You feel somewhat invincible’

Made famous by the 2001 film “Black Hawk Down” and his own book, “In the Company of Heroes,” Durant piloted a Black Hawk helicopter that was shot down during the Battle of Mogadishu in 1993.

His Special Operations aviation unit was deployed to Somalia in August 1993 to assist U.S. forces that had been engaged in the country for roughly eight months. The year before, President George H.W. Bush had ordered thousands of U.S. troops into the war-torn country, leading a United Nations effort to ensure food supplies for starving people.

The unit’s overall goal was to capture the leader of a Somali clan named Mohamed Farrah Aidid and provide security for relief organizations that were giving aid to the hungry in Mogadishu. At the time, Somalia was being ripped apart by clan warfare after the downfall of its former strongman ruler, Mohamed Siad Barre.

That summer, Durant and his team of U.S. soldiers conducted several successful operations, capturing around two dozen Somali warlords.

But everything changed on October 3, 1993, when his elite helicopter unit was tasked with providing air support for ground forces as they hunted two of Aidid’s senior militia leaders in the country’s capital.

Along with other armed opposition groups, Aidid’s forces were instrumental in driving out President Barre and spearheaded the effort to challenge the U.S.-led NATO presence in Somalia at that time.

Durant was riding a rush of adrenalin as he climbed into the cockpit of his helicopter that day, a feeling he compared to playing in the Super Bowl.

“We’re flying Delta Force and SEAL Team Six into the target … I mean, it doesn’t get any better than that,” he said. “When you first dream about getting involved in in military aviation, you put that as the highest level you could ever achieve.”

Confidence was high as the team of U.S. Black Hawks flew in formation from the United Nations compound on the outskirts of Mogadishu toward the city center.

“You feel somewhat invincible,” Durant said. “I mean, even today when I look at the videos of us flying in formation, it’s pretty intimidating.”

The operation was intended to last only an hour or two, using an assault force made up of 19 aircraft, 12 vehicles and 160 men.

Circling high above the targeted drop area, Durant and his three-man crew could see a battle begin to escalate below. U.S. ground forces had engaged Somali militia members and armed civilians who were loyal to Aidid and controlled the urban interior of the city.

As the firefight raged, Durant flew his aircraft into a tight orbit around the combat space to provide fire support for the U.S. troops below.

Suddenly, a man stepped out from a doorway and fired a rocket-propelled grenade toward the slow-moving helicopter, hitting its tail and sending Durant and his crew spiraling violently toward the ground.

The Black Hawk spun an estimated 15 to 20 times from about 70 feet in the air and crashed into a shanty area near where the main battle was taking place.

“I think in my mind, I died,” Durant said, thinking back on moment the helicopter hit the ground. “But somehow we didn’t.”

‘We are alone, we are surrounded’

When Durant regained consciousness after the crash, he immediately knew the situation was dire, but he did not panic.

“It’s like coming out of a deep sleep,” he said. “I remember regaining consciousness and thinking, OK, what do I need to do?”

Realizing that he could not exit the helicopter, as his back and leg were badly broken, Durant pushed away the debris blocking the windshield to get a better view of the situation. He found the personal weapon that was lying next to him and prepared to make his final stand.

“We are badly injured, we are alone, we are surrounded and there are really no reinforcements left to come to our aid,” he said.

But just as he had come to terms with his fate, two Delta Force operators, Master Sgt. Gary Gordon and Sgt. 1st Class Randy Shughart, suddenly appeared at the crash site.

Durant would later learn that Shughart and Gordon had volunteered to drop into the crash site from one of the other U.S. helicopters providing suppressive fire from above, despite the heavy volume of Somalis in the area and not knowing if Durant or his crew had survived impact.

Both men were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions that day.

“I felt like somehow, miraculously, a reaction force has gotten here much faster than I would’ve ever thought possible,” Durant said.

He felt that he and his crew were going to make it out of the situation alive. But that hope evaporated only two or three minutes later, once Durant realized that the two men standing beside him made up the entire rescue operation.

With gunfire raging all around the downed helicopter, Durant recalled the way Gordon and Shughart seemed completely calm, setting up a perimeter and making radio calls as they were trained to do.

They held off the mob for a time, exchanging volleys of gunfire with the Somalis who had surrounded the chopper. But the prospect of a successful rescue slipped away with each passing moment.

Durant said the relief he had felt when the two Delta Force operators showed up dissolved the moment Gordon was shot.

“It’s like being shot down initially,” he said, “because now one of the guys you thought was indestructible has just been taken down.”

Durant was assessing the injuries of the rest of his crew when he heard Shughart make his last stand.

“The volume of gunfire was unbelievable,” he said. “I kind of knew there was no way he could hold them all off.”

Then the shooting stopped, and Durant knew Shughart was down. He said the moments that followed were the most fearful of the entire battle.

“I remember just trying to come to terms with it, looking up to the sky and thinking I can’t run, I can’t fight, and I can’t hide. … It’s over,” he said.

The three men in Durant’s crew were killed as the Somalis stormed the crash site, but Durant did not die that day. Instead, he was thrown into the back of a pickup truck and taken prisoner by a local warlord.

Eventually, ‘the Somalis liked me’

While in captivity, Durant had one mission: Try to survive.

Initially, Durant says, his captors treated him badly. Despite nursing severe injuries from the crash and subsequent beating, he was shot in the leg while being held prisoner, constantly threatened by guards and kept in deplorable living conditions.

He remembers how the Somalis had tied him with a dog chain, wrapping his hands together so he couldn’t even wipe the dirt from his face.

They kept him in a concrete room with no furniture and only one door, which remained closed.

But day by day, they became less hostile.

Despite the cultural differences, Durant was able to build a rapport with the guards by using his sense of humor, to the point where the Red Cross determined that his captors experienced “reverse Stockholm syndrome.”

“My way of dealing with stress is to make jokes,” he said. “Basically, their (the Red Cross) conclusion was that the Somalis liked me.”

While in captivity, Durant said, he never lost hope that he would be freed.

“You have got to be hopeful … telling yourself that someday, I’m going to get out of here to keep yourself motivated psychologically,” he said.

And after 11 days, Durant was released back into U.S. custody after negotiations spearheaded by American diplomat Robert Oakley.

But he did not fully accept that the ordeal was over until he walked through the gate of the United Nations compound that he had taken off from 12 days earlier.

Once securely inside the base, Durant was comforted by familiar faces, but was also greeted by more, unexpected heartbreak.

“When they brought some of the guys from the unit over, that was a very emotional moment because, first of all, I got to see these guys. But that’s also where I found out that two of our very close friends, Donovan Briley and Cliff Wolcott, had been killed,” he said. “I knew my crew was gone, I had 11 days to kind of come to terms with that, but I didn’t know two other very good friends were gone.”

Claims insufficient resources

Durant was still reeling from the news when he received a call from President Bill Clinton.

“I just told him that I was proud to be an American, or something stupid like that,” he said. “I didn’t tell him what I really wanted to say.”

Looking back on his conversation with Clinton, Durant says he was adhering to the obligation of those who serve in the military to not to openly criticize civilian leaders. But the reality is that what happened in Somalia is “absolutely the fault of our civilian leadership at the time,” he said.

“We didn’t have the resources we needed to do that mission. We had asked for them, they were denied, and the results speak for themselves,” he said. “We took what was a very successful operation that had gone on for 10 months and turned it into what, unfortunately, history will always look at, overall, as a failure.”

“It was a tough pill to swallow to know that you and your friends did everything you could do, fought your tails off in that battle, and our hands were tied because of political decisions, which is unacceptable,” he added.

Eighteen soldiers in the U.S.-led force were killed and 74 were wounded in the Battle of Mogadishu.

‘I’ve been given this second life’

Durant had to face another difficult reality upon returning to U.S. soil: His experience had made him famous.

“Some people like being the center of attention, but I don’t,” he said.

While in captivity, Durant had little idea of how much the media had covered his story and the public interest that awaited him at home.

“For a long time, I was pretty bitter about the whole thing because, you know, my friends are dead and within 90 days, the U.S. withdrew all forces from Somalia and basically gave up,” he said.

But today, Durant says, he understands why his experience resonated so deeply with people all over the world and recognizes that some good has come from the terrible events in Mogadishu.

“Something I am still not comfortable talking about, but it is part of the story, is when American bodies are dragged through the streets … the shock factor goes up another level,” he said.

The media frenzy just after his release, in many ways, made Durant the face of the U.S. involvement in Somalia.

While the news coverage was, at times, overwhelming, he said the exposure highlighted the fact that the U.S. military needed to adapt to the realities of modern, unconventional warfare.

“If Somalia doesn’t happen, we aren’t as ready for the war on terror,” he said. “To me, that is the one silver lining to what happened. … I truly believe it left us better prepared for the conflicts that we face today.”

On a personal level, Durant said his experiences in Somalia have had a lasting impact on the way he approaches life.

“If I face challenges or setbacks, I put it in perspective by saying I should be dead,” he said. “I’ve been given this second life that’s almost as long as my first life, at this point.”

That attitude has helped Durant find personal and professional success in his “second life.”

Not long after his release, the Army told him that he would not be allowed to fly again, because of his physical injuries.

But that only fueled his desire to get back into the cockpit. After only 10 months of healing, Durant ran the Marine Corps Marathon, an accomplishment that gave him the confidence to sign a waiver and eventually fly for five more years.

He also said he probably would not have started his own company if it weren’t for what happened to him in Somalia, as his experience opened his view to new possibilities outside of being a pilot.

His company, Pinnacle Solutions, has grown significantly since he founded it in 2008. Nearly 85% of the people he employs are veterans.

‘The ghosts are gone’

Today, Durant says his injuries give him very little physical discomfort, and he is able to play hockey on a regular basis. But like many, many vets, he says the psychological healing process was incredibly difficult.

While he has never experienced many of the negative effects usually associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, he admits that he struggled to deal with grief for a long time.

“There was a time where I cried every day,” Durant said. “It would be a wave of emotion that just came over me … my friends are dead, and if that doesn’t bother you, then you are made of something different than I am.”

Telling his story has helped Durant heal. He now travels across the country speaking to various groups.

“Telling the story was absolutely therapeutic for a long period of time,” he said. “I didn’t realize it, but one theory I have about why I don’t think I suffer from most of the symptoms that would be associated with PTSD is that I have told this story.”

“The ghosts are gone,” he added.

But just after he returned home, Durant says, the media attention affected his relationship with his family, specifically his first wife, Lorrie.

“The media is very aggressive, and if there’s a big story, pretty much anything’s going to be done to try to get that story,” he said, adding that his handling of some situations with the media “probably became a contributing factor” to his divorce.

Despite the divorce, Durant said his experience in Somalia is almost a “nonfactor” in terms of his relationship with his six children. Most of them were either very young or not yet born when he was shot down, and his experience in Somalia isn’t now part of his family’s daily life.

“Every once in a while, there’ll be something that comes up in the news about it, or someone will recognize me somewhere, and the topic will come up, and so they all know,” he said. “But it isn’t who we are. It doesn’t define us, at all.”

And while his time in Somalia has had a significant impact his life, Durant doesn’t want people to see him as just “the ‘Black Hawk Down’ guy.” He’d rather they see his accomplishments as a businessman and parent.

However, he said, he does understand the lasting relevance of his story and the way it has shaped the man he has become.

“Whether it sounds good or not, in the end Somalia has turned out to be a great thing for me, because of the effect that it’s had on me and the opportunities in my life,” he said.

“Is Somalia a good thing? It’s a horrible thing. But, you know, I guess there’s something to be said for taking something horrible and finding a way to make it in any way positive.”