Death hunted Scott O’Grady for six days.

In the summer of 1995, the Air Force captain was flying over Bosnia, enforcing the no-fly zone when a surface-to-air missile slammed into his F-16.

He parachuted into enemy territory and for almost a week he evaded the trigger-happy Serbian paramilitary forces that wanted to kill him.

Even after he was rescued on a mountaintop by U.S. Marines, O’Grady wasn’t safe. As he sat — shivering, hungry, dehydrated — aboard a helicopter flying him out of the combat zone, the chopper and another in the rescue team took ground, anti-aircraft and missile fire. A bullet bounced off a canteen belonging to a Marine sitting a few feet away from the rescued pilot.

O’Grady spent just two days on the USS Kearsarge getting medical care before he was hustled back to the United States for a feel-good tour for a nation that needed an emotional boost after the terrible bombing two months earlier of a federal building in Oklahoma City that killed 168 people.

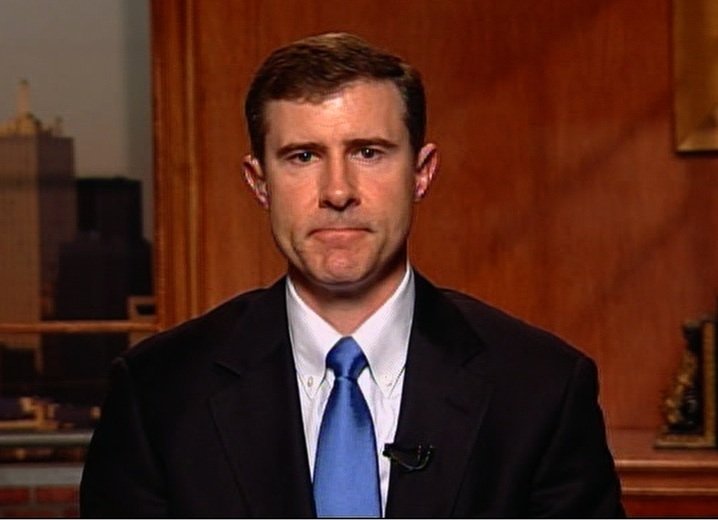

O’Grady was everywhere. He went to the White House, where President Bill Clinton called him an “American hero.” He appeared on “The Tonight Show,” he did an hour with CNN’s Larry King and was interviewed on the network morning shows.

His face was on magazines. Everyone knew of his courage and will to survive.

They all wanted to hear how he evaded capture, how he survived trekking through the woods and up mountains. They wanted to know how he found his strength.

He told them how his faith in God, country and his desire to see his family got him through, but he also wanted to impart how the experience changed his view about material things and his wants.

“I was always living in my future,” he recently told CNN at his real estate office in Dallas. “I learned that there’s no guarantee that tomorrow will come. And it’s OK to plan for your future, but that you need to be content and happy with where you are and what you’re doing in life at this very moment. Or happiness will escape you.”

The constant attention he used to get in public, often at his motivational speeches, is gone 20 years later. He looks much the same, but it’s rare that anyone recognizes him immediately.

That seems to suit him just fine.

Dream job

Scott O’Grady always wanted to be a pilot. His father, who was in the Navy, took him up for the first time when he was 6 and the family lived in California. Scott got his pilot license when he was teenager after the family had moved to Spokane, Washington.

“It was just my dream to pursue it,” he said.

O’Grady attended Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s campus in Prescott, Arizona, joined the ROTC and set his eyes on the Air Force.

In December 1989, O’Grady began his year of military pilot training. O’Grady said everyone in his class wanted to be a fighter pilot, but where you were assigned depended on class rank, which planes were available and the Air Force’s needs.

“I was fortunate,” he said. “I was very, very happy to get the F-16.”

O’Grady spent the next two years learning tactics and weapons systems, focusing on the craft of becoming a fighter pilot. While based in South Korea, some of his missions involved flying along the demilitarized zone between the North and the South.

O’Grady’s next assignment was in Germany, from where he would fly combat missions in the no-fly zone over northern Iraq.

Seeing combat

After his unit in Germany was shut down, O’Grady went to Aviano Air Base in Italy to fly NATO support missions over Bosnia.

In the early 1990s, Yugoslavia — a multiethnic state of Serbs, Croats and Muslims — dissolved into six countries and bloody conflict broke out. Bosnia-Herzegovina was the site of some of the worst fighting — almost 100,000 people died in the civil war, many of them in “ethnic cleansing.

NATO’s involvement began in 1992, and O’Grady said U.S. jets often helped U.N. troops on the ground.

“A lot of times we would fly by, if they asked us to, just so that people on the ground could hear us. And that alone would deter them from their bad actions,” he said. “Other times, we’d be given direct orders to go ahead and drop bombs in defense of the U.N. troops on the ground. That would be a rare occasion.”

O’Grady helped make NATO history when he became part of its first combat mission.

On February 28, 1994, O’Grady was Capt. Robert Wright’s wingman when eight Serbian jets struck a target in northwest Bosnia.

Wright engaged the Serbs as two more F-16s joined the attack. Wright downed three enemy planes with his missiles, and Capt. Stephen Allen was credited with downing one plane.

“I don’t know if they expected that we would actually shoot ’em down,” O’Grady said, explaining that the no-fly zone had been violated many times before.

The fateful day

Sixteen months later, on June 2, 1995, O’Grady and Wright were flying over what had become a more turbulent country.

It was another routine combat air patrol in which they were flying an oval pattern over northwest Bosnia. There were known fixed missile sites along much of the route, but there was a mobile site that had not been spotted by intelligence units.

At one point, Wright’s detection system relayed a very quick warning of a potential threat. But no one on the ground spotted a threat.

The military would find out later that a U-2, a high-flying reconnaissance plane, had picked up an illumination from the mobile site just a few minutes before O’Grady’s plane was struck but wasn’t able to get a message to the two pilots.

Two missiles were fired without radar assistance (so the Serbs could avoid being detected). The Serbs turned on the radar when the missiles were just seconds away from O’Grady’s and Wright’s jets.

“I received an illumination inside my threat warning system. And now I’m looking out to see if I see any missiles being shot at us. I never saw them,” O’Grady said.

One missile shot between the two fighters; the other SA-6 blasted O’Grady’s plane 10 feet behind his seat. As O’Grady ejected, the pilot was encased in flames and worried his parachute would burn up. So instead of waiting for a lower altitude where the chute would deploy automatically, O’Grady yanked the override handle. He breathed easier when the chute opened up above him.

It would take him more than 25 minutes to fall into a clearing just south of a highway, making his white, brown, green and orange chute a trackable target. As he descended, O’Grady could see paramilitary soldiers in chase. He couldn’t steer his chute but fortunately no one was firing at him.

Compounding his crisis, his face and neck were burned by the explosion.

With forces closing in, O’Grady tumbled onto the ground, ripped off his chute, grabbed some of his survival gear and raced to the woods.

“And within moments, we had people walking right by me,” O’Grady said. The first two were a man and a boy, only 6 feet away.

No doubts

O’Grady, 29 at the time, never lost faith that he would make it out alive.

“No, never. I mean, it was actually the opposite. My faith grew from this experience,” he said. It was more than his faith in God that helped him; it also was faith that he would be rescued.

The enemy often was close. During the first two days, a helicopter was so near, he could see the faces of the Serbian pilots. Men on the ground were shooting at things that moved.

He moved at night, occasionally trying his radio to call for help. He fought the wet conditions, thirst and hunger. He ate ants and plants and drank the water he had in his emergency pack until that ran out on the fourth day. Rain brought more water, but it also soaked him. He developed trench foot from the prolonged exposure to cold water.

On the sixth night, using the call sign Basher Five-Two, he made contact with one of his squadron mates (who was flying on extremely low fuel) and soon four Marine helicopters were headed more than 80 miles into enemy territory. About 40 other aircraft kept watch nearby in case the Serbs caught on to the rescue attempt.

On the morning of the sixth day, they found him, sprinting from the woods into a small opening, 9mm pistol in his hand in case there was enemy fire.

A team of Marines covered him as he got into one of two CH-53E Super Stallions. Two AH-1W Super Cobra helicopter gunships flew nearby in case the enemy fire on the way out became a problem. Those Marines were the heroes, O’Grady said. “I was just doing my job,” he added.

Within days of June 8, 1995, O’Grady’s face was everywhere. He returned to a country that had witnessed its own tumult in the years he was deployed: Riots in Los Angeles after the Rodney King verdict, the Branch Davidian standoff in Waco, Texas, and the Oklahoma City bombing.

In September that year, he joined the Air Force reserves and was based in Utah until he left the service.

Finding a home in Texas

Twenty years later, the face is the same, even though the hair has tinges of gray and he requires reading glasses.

Life is a lot less hectic. There’s no more spending more days than not on the road, telling his story or selling books. Now it’s the very occasional speech; mostly he travels to see family.

While he goes through life these days without being recognized, O’Grady still finds letters in the mailbox of his Dallas-area home and messages on the answering machine thanking him for his service and for his survival story that inspires others to persevere.

Most days you’ll find him at Wellington Realty, a Dallas-based commercial real estate investment company with clients in the four largest markets in Texas. O’Grady said his role is to help bring in client and investors and build relationships.

“When I engage them, they understand that I’m coming from a background of somebody that they can trust and that I’m reliable and I’m gonna be honorable to them,” he said.

Despite not having any real estate experience when he joined the company four years ago, O’Grady said he likes his work and loves his colleagues and clients.

O’Grady isn’t a Texan by birth, but he is a Texan by God.

He came to Dallas about 12 years ago to take biblical studies classes part time. He wasn’t planning on staying in Texas but really liked the community and made some good friends through church.

O’Grady was still giving motivational speeches and had co-written two books — “Return With Honor” and “Basher Five-Two.” He was a spokesman for a few companies. He traveled up to 300 days a year though the demands of time were beginning to lessen.

O’Grady, born in Brooklyn, lived in several towns while his father was in the Navy. There were a few years in Long Beach, California; and Ridgewood, New Jersey. He spent 10 years in Spokane.

But Texas is home now. It’s a great place for an avid outdoorsman who has similar values to many in this conservative state. He even briefly ran for state Senate as a Republican a few years ago.

He loves to hunt and fish. He gets fired up about going to the gun range. At a visit to the DFW Gun Range, O’Grady showed off keen accuracy, but he also got excited when his two “pupils” follow his guidance and pulverize a target, too.

While he enjoys shooting paper targets, he also likes to go after feral hogs.

The hogs are a huge problem for Texas farmers and good eating, and O’Grady and his friends relish their weekends when they go hunting.

One night over dinner, O’Grady listens as his good buddy, Joe, tells stories. O’Grady is the guy at the table who is quiet for much of the conversation, choosing to economize his words. His eyes smile as Joe recounts their adventures.

Faith, family, country

When asked to talk about his service, however, O’Grady’s passion for the military comes out. It’s the same sentiment he puts into his motivational talks. People love to hear what it’s like to have been a pilot on combat. They eat up the stories he tells about his six days in the midst of the enemy.

“But then I do ultimately use that vehicle of a story to deliver the messages of motivation and priorities in life,” he said. “Ultimately, I don’t deviate from my message of the priorities in my life being my faith and family values and my patriotism as well as those being the motivators that gave me the will to survive.”

Now 50, O’Grady told CNN he doesn’t have traumatic memories, despite coming close to death several times over those six days. Other service members had it worse, he said, especially those who face multiple tours in combat. He even looks at the physical ailments — neck and back pain — as something to be accepted as part of his duty and as minor compared with what many others who served face.

All fighter pilots have similar issues, he said, while acknowledging his ejection made the pain a little worse. Yoga helps some, and he also has a neck traction device he uses daily.

But at the Frontiers of Flight Museum, he moves around with no trouble. You don’t even think about how he was hurt until you see the Purple Heart license plate on his SUV.

O’Grady keeps some details about his life private but he did share with CNN his desire to serve others.

He is on the board of Sons of the Flag, a charity that helps burn victims. It was founded by a former Navy SEAL but now also seeks to assist firefighters and others who have been injured by flames.

“When you see somebody that’s severely burned, especially a child, you know, your heart just goes out to them,” he said. “(Sons of the Flag) is really helping to change lives and help those that are suffering greatly.”

O’Grady said he he’d like to be remembered as someone who was a good person, a guy you could trust, as someone who cared.

As a hero? No. Those were the other guys.