Scientists have discovered you can teach one of the most maligned of birds how to identify cancer.

It turns out pigeons may make great cancer detectives.

It’s unlikely that you’ll see a “Pigeons at Work” sign at the hospital radiology or pathology department anytime soon, but the authors of a new study in the journal PLOS ONE think the birds offer great potential as testers of cancer detection technology and as a help in doctor training.

Evolutionarily speaking, birds’ and humans’ last common ancestor lived about 310 million years ago, but pigeons’ vision is as effective as that of humans, if not better. The birds can see more wavelengths of light than we can, including ultraviolet light. And that’s impressive when you know that their brains are about one-thousandth the size of ours.

Earlier studies have shown pigeons can use visual cues to put objects into categories, they can differentiate between letters of the alphabet, and they can recognize you even if you change clothes. (Maybe it really is personal if your car, or head, is a target for droppings.)

Hearing about this amazing visual recall on a radio segment, Dr. Richard Levenson wondered, out of a kind of “intellectual playfulness,” if he could harness that pigeon power for good. Levenson is a professor and vice chair for strategic technologies in the department of medical pathology and laboratory medicine at University of California-Davis Medical Center. He wondered “if they could actually do pathology, which is all about visual recall,” Levenson said.

In other words, would the proverbial “rat with wings” make a good lab rat with wings? Did the birds have enough of an eagle — er, pigeon eye to detect cancer in tissue samples?

He got in touch with Dr. Ed Wasserman, a professor of experimental psychology at the University of Iowa. He is also one of the guys scientists flock to when they want to play with pigeon vision.

The collaboration was a success. “It worked spectacularly well,” Levenson said. “In fact, Ed (Wasserman) said that the pigeons responded to this visual challenge as well, or better than many other tests.”

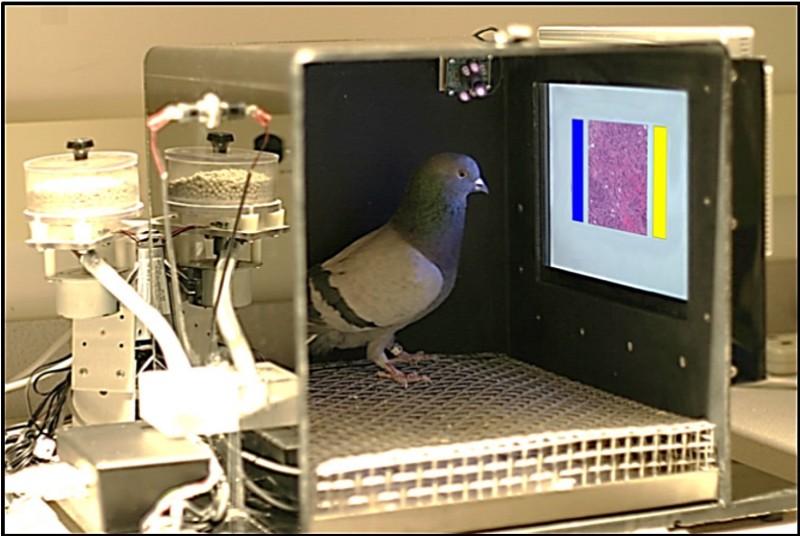

For the experiment, eight birds were placed in a high-tech box in which they were shown an image a scientist would see under the microscope, along with two boxes. The slides showed relatively straightforward images of cancer cells, and cells that are not cancerous, from actual breast tissue samples. The scientists trained the birds to peck at one box if the sample was malignant, the other if it was benign. The birds trained with 144 images at different magnifications and each got a pellet when it pecked at the box with the right answer.

Over 15 training days the birds were able to tell the difference, even with images they hadn’t seen before. The pigeons showed “remarkable” success, getting the right answer 85% of the time. The birds did better with color images than black and white, but when the birds did a little “flocksourcing” and worked together to identify the images, their accuracy rose significantly.

The birds didn’t do as well classifying suspicious mammographic densities or masses. In that case birds mostly memorized and weren’t as successful identifying the novel cases. Inexperienced human students may also struggle with these same images.

The difficulty does not surprise Dr. Debra Monticciolo, chairwoman of the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Commission. “Unlike looking at the heart or lungs, which look pretty much the same (in all patients), what makes this field incredibly difficult is that every woman’s breast looks different based on different patterns of fat and density patterns,” Monticciolo said. “That’s why it takes many years’ experience to do this kind of work and why people get better at it the more images they study.”

With medical school, four years of radiology training and residency on top of that, a radiologist will have seen hundreds of thousands of cases before he or she is licensed to make what may be a life-or-death cancer diagnosis.

So Monticciolo doesn’t expect to share her lab with pigeons any time soon, “although they would have an advantage since they work for peanuts,” she joked. She said she appreciates this “innovative study,” not just because she recently came back from a birding trip in Brazil.

Levenson and his co-authors are not proposing pigeons replace human experts. But the authors do wonder if pigeons may someday be used the way computer algorithms are used today in testing new medical diagnostic technology, as a substitute for expensive human testers in the early stages of development.

Also, if pigeons consistently miss the same things, maybe humans in training would too. Levenson wonders if textbook authors could use pigeons to determine which images are trickier and include more of those images to boost training.

And on a grander scale, he added, perhaps knowing the good work pigeons are capable of will improve their public relations image. Instead of cursing them as a nuisance, maybe people will appreciate them for their hidden talents.

“What is going on inside their brain is not nearly as crude as people think,” Levenson said. “They may in fact have a rich inner life.”