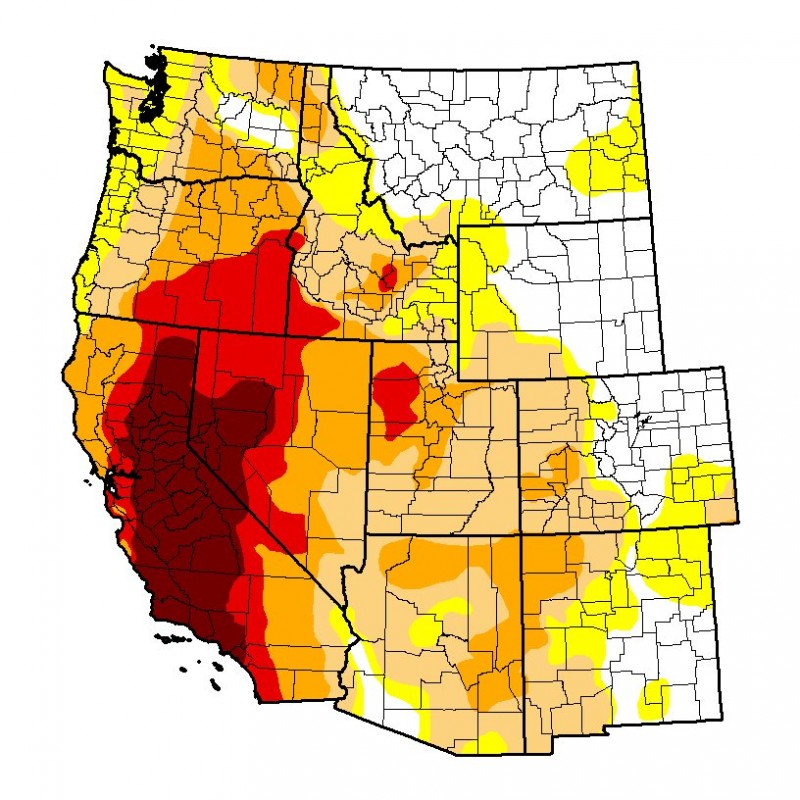

It’s not just California. Droughts are sapping precious water supplies all across America’s southwest.

The region has been suffering from drought for 11 of the past 14 years, according to NASA, directly affecting more than 64 million people.

In Arizona and Nevada, the water level in Lake Mead — which feeds water to 40 million people across the region — has plummeted to lows not seen since the 1930s, according to the Los Angeles Times.

And then there’s Texas — which has been battling its current drought for nearly five years.

Long-term weather forecasters predict it could get a lot worse. A NASA study warns that greenhouse gases from fossil fuel emissions might create “megadroughts” in the western U.S. during the coming decades. These events could trigger “events that nobody in the history of the United States has ever had to deal with,” NASA climate scientist Ben Cook says.

Without snow and rainfall, what’s the alternative? Communities in Texas, Arizona, New Mexico and Nevada are considering more reliance on two sources: “brackish” or salty water found underground and seawater.

The process is called desalination.

In Texas — which like California, boasts hundreds of miles of ocean shoreline — water levels in some reservoirs are extremely low. Farmers in parts of the state have suspended crop irrigation. Communities have restricted water use. Cities need water to generate energy, and thirst for electricity is skyrocketing.

“There’s 1,000 people a day moving into Texas and there just won’t be enough water unless we do something about creating new resources,” says Mark Lambert, CEO of a water treatment firm called IDE Americas.

In San Diego, Lambert’s company has built the biggest seawater desalination plant in the Western Hemisphere, a $1-billion facility expected to go online as soon as November, producing up to 50 million gallons of freshwater a day by a process called reverse osmosis. Lambert expects the desalination plant to result in a $5 to $7 spike in average monthly water bills.

In Florida, a desalination plant in Tampa Bay transforms seawater into as much as 25 million gallons of freshwater daily. That’s 10% of the company’s 2.3 million customers. About a hundred miles south, Cape Coral, Florida, boast the oldest municipal reverse osmosis desal plant in the nation, dating back to 1977.

When it comes to changing seawater to freshwater, Texas is watching.

Texas predicts its population will skyrocket 82% between 2010 and 2060, but its water needs will increase just 22%. The projection factors in declining demand for irrigation and increasing municipal conservation.

“We’ve certainly spent a lot of time looking at what Tampa Bay has done in Florida with their seawater desal project,” says Robert Mace, Texas deputy executive administrator for water, science, and conservation. “And then we’re certainly looking very closely at that project that San Diego has for water supply.”

For years, Texas communities have used desalination plants to purify brackish water from underground. San Antonio — the state’s second most populated city — is building a plant for brackish water set to go online in 2016. But Texas has no major plants that desalinate seawater.

Instead of desalination, state water officials are emphasizing conservation, including facilities that transform waste water directly into drinking water.

“There’s a great deal of potential in reusing water in Texas,” Mace says. The state’s “direct potable reuse” facilities have been attracting interest from other states, including California, Mace says.

But experts acknowledge desalination, especially from seawater, will eventually play a large role.

Building more desalination plants “probably should have happened a decade ago,” Lambert says.

“I’m not saying desalination is a silver bullet. It’s a part of the solution.”

Environmental groups have been cautiously supportive. When Texas lawmakers hammered out new legislation in March for seawater desalination plants, the Sierra Club’s Ken Kramer told a Texas House committee that each proposed seawater desalination plant should be thoroughly reviewed “to make sure that it is the most viable approach to meeting a true water supply need and … to avoid or minimize the potential effects on marine life and the environment.”

A few basic methods for desalination include:

Reverse osmosis

This process uses high water pressure. Undrinkable salty or brackish water is pushed at high pressure through a membrane filter. Pure water molecules then exit the other side.

Thermal

This one is all about the heat. When you raise the temperature of the water, it evaporates, leaving the salt behind. The evaporated water condenses in a separate chamber and becomes pure water.

Electrolytic

Electricity is the key to this process. Salt in water is made up of atoms called ions that have electrical charges. By sending electricity through salt water and a stack of filters, the process can separate the salt, leaving pure water.

The immediate prospects for Texas seawater desalination are minimal. Next year, a seawater desalination plant is expected to go online in Corpus Christi, Texas. Italian chemical company M&G Resins is building its own private desalination facility for manufacturing. It’s expected to pump out 6 million gallons of freshwater a day.

There’s also been discussions in communities such as Brownsville and the Galveston-Houston area about building seawater desalination plants.

“Desalting seawater is very expensive compared to other water supplies,” Mace says.

“As other water supplies get allocated or used, seawater desal will probably become more desirable.”

Lambert agrees. There “will be a time in the relative near future when desalinated water becomes the cheapest source of water” as the price of water from other sources rises, he says.

Overall, expect the search for new water sources in the southwestern U.S. to be permanent, says Lambert. “This isn’t a blip on a radar screen.”