Three days after bikers turned a Texas parking lot into a battlefield, police are expected to leave the scene of carnage Wednesday.

What happens next is anyone’s guess.

Will rival motorcycle clubs peacefully mourn the nine bikers killed in Sunday’s shootout at a Twin Peaks restaurant? Or will there be more violence, either against police or against other bikers in retaliation?

Waco police Sgt. W. Patrick Swanton said more trouble may come.

“Is this over? Most likely not,” he said Tuesday.

But there are signs that many of the bikers want peace. The Cossacks Motorcycle Club, one of the groups at Sunday’s melee, has agreed to cancel its 14th annual Mingus Blowout party, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported.

The event was scheduled for this weekend in Palo Pinto County, about 100 miles (161 kilometers) northwest of Waco.

“We never had a problem before,” Palo Pinto County Sheriff Ira Mercer told the Star-Telegram. “But in light of Waco, I don’t think it’s safe right now.”

How it all started

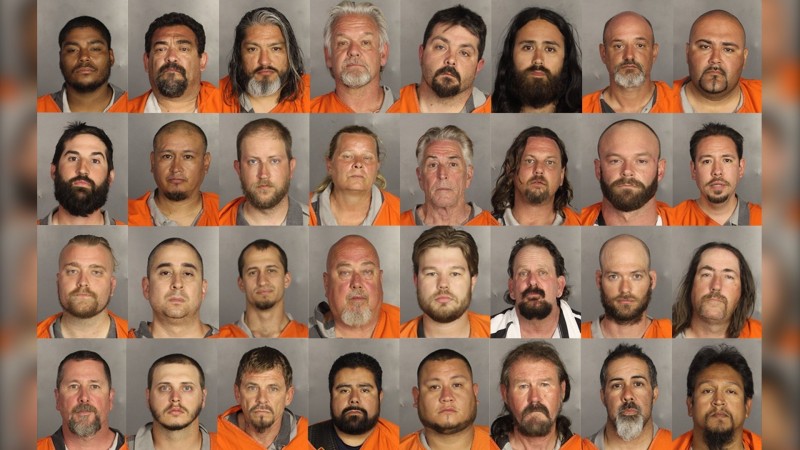

With seven bikers still hospitalized and 170 suspects in custody, authorities have a complex investigation on their hands. But more details are starting to emerge as to what exactly happened Sunday.

Swanton said a coalition of motorcycle groups had reserved the outdoor bar area at Twin Peaks when “an additional biker gang” showed up, uninvited.

A disturbance in the parking lot ensued. Swanton said that quarrel may have involved a tiff over a parking spot or someone having his foot run over.

The arrest warrants for some suspects offered even more details: Members of the Cossacks were in the Twin Peaks parking lot when members of the rival Bandidos biker gang arrived.

But the ruckus didn’t stop there. Swanton said there were “crime scenes inside and outside” the restaurant, including in the bathroom, dining area and around the bar.

The assailants used all sorts of weapons — brass knuckles, guns, knives and chains. And when police responded, some bikers turned their weapons on them, Swanton said.

He said that three or four Waco officers probably opened fire but that it’s too early to tell how many of the dead bikers may have been struck by police bullets.

The Southwestern Institute of Forensic Sciences said the nine killed ranged in age from 27 to 65, and all died from gunshot wounds.

As for the 170 people locked up in the McLennan County Jail, each has $1 million bail on charges of engaging in organized crime. Police said some might later have capital murder charges filed against them.

Long-brewing feud

A May 1 memo from the Texas Joint Crime Task Force warned that the violence between the Bandidos and Cossacks “has increased in Texas with no indication of diminishing,” WFAA-TV in Dallas said.

It all comes down to territory, according to a government informant and a police detective who has infiltrated biker gangs.

Both the Bandidos and Cossacks call Texas home, though they have members elsewhere.

The Bandidos have been the biggest and most dominant, and while they “allow other motorcycle clubs to exist, they’re not allowed to wear that state bottom rocker,” according to a government informant who goes by the name “Charles Falco”

“If they do, they face the onslaught of the Bandidos.”

A state bottom rocker is the state name on the back of a biker’s vest. It looks like the curved bottom of a rocking chair, hence the name.

The rocker can indicate where someone is from, but it’s also a territorial claim for that club. That’s why the Bandidos and Cossacks aren’t getting along, Falco said.

“The Cossacks decided that they were big enough now to go ahead and wear the Texas bottom rocker, and basically tell the Bandidos that they’re ready for war,” he said.

More violence ahead?

Falco doesn’t think another battle is imminent, saying biker gangs prefer to lie low. But he said that these groups “like participating in war” and take assaults on their pride seriously.

“Anytime a biker gang war starts, it never stops,” said Falco, who infiltrated biker gangs for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

“Thirty, forty years from now, you’ll still be reporting about these biker gangs fighting each other. The war will never end.”

The Department of Justice lists the Bandidos among the most notorious “outlaw motorcycle gangs,” saying the group is involved in drug trafficking and poses “a serious national domestic threat.”

But Jimmy Graves, a high-ranking Bandidos member, says his club is not a criminal gang.

“We are not a gang. We do not do gang things. We are not affiliated with gangs,” he said.

Graves bemoaned “lies on TV, (including) telling everybody that the Bandidos are after police departments.”

“We’re not like that,” he said. “The ’60s are long gone.”