When Etan Patz went missing in New York City at age 6, hardly anyone in America could help but see his face at their breakfast table.

His photo’s appearance on milk cartons after his May 1979 disappearance marked an era of heightened awareness of crimes against children.

On Friday, more than 35 years after frenzied media coverage of his case horrified parents everywhere, a New York jury will again deliberate over a possible verdict against the man charged in his killing, Pedro Hernandez. He confessed to police three years ago.

Severe mental illness?

Etan Patz’s parents have waited that long for justice, but some have questioned whether that is at all possible in Hernandez’s case. His lawyer has said that he is mentally challenged, severely mentally ill and unable to discern whether he committed the crime or not.

Hernandez told police in a taped statement that he lured Patz into a basement as the boy was on his way to a bus stop in Lower Manhattan. He said he killed the boy and threw his body away in a plastic bag.

Neither the child nor his remains have ever been recovered.

But Hernandez has been repeatedly diagnosed with schizophrenia and has an “IQ in the borderline-to-mild mental retardation range,” his attorney Harvey Fishbein has said.

A long interrogation

Police interrogated Hernandez for 7½ hours before he confessed.

“I think anyone who sees these confessions will understand that when the police were finished, Mr. Hernandez believed he had killed Etan Patz. But that doesn’t mean he actually did, and that’s the whole point of this case,” Fishbein has said.

But in November, a New York judge ruled that Hernandez’s confession and his waiving of his Miranda rights were legal, making the confession admissible in court.

Another suspect?

Another man’s name has also hung over the Patz case for years — Jose Antonio Ramos, a convicted child molester acquainted with Etan’s babysitter. Etan’s parents, Stan and Julia Patz, sued Ramos in 2001. The boy was officially declared dead as part of that lawsuit.

A judge found Ramos responsible for the boy’s death and ordered him to pay the family $2 million — money the Patz family has never received.

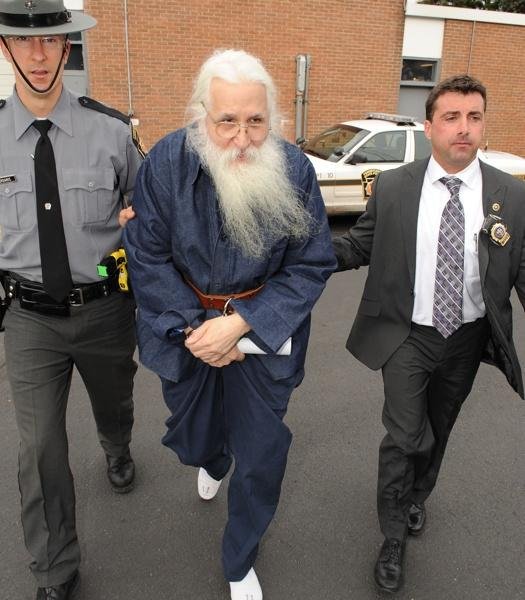

Though Ramos was at the center of investigations for years, he has never been charged. He served a 20-year prison sentence in Pennsylvania for molesting another boy and was set to be released in 2012.

He was reportedly immediately rearrested upon exiting jail in 2012 on failure to register as a sex offender.

Dawn of child protection

Since their young son’s disappearance, the Patzes have worked to keep the case alive and to create awareness of missing children in the United States.

In the early 1980s, Etan’s photo appeared on milk cartons across the country, and news media focused in on the search for him and other missing children.

“It awakened America,” said Ernie Allen, president and chief executive officer of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. “It was the beginning of a missing children’s movement.”

The actual number of children who were kidnapped and killed did not change — it’s always been a relatively small number — but awareness of the cases skyrocketed, experts said.

But the news industry was expanding to cable television, and sweet images of children appeared along with destroyed parents begging for their safe return. The fear rising across the nation sparked awareness and prompted change from politicians and police.

In 1984, Congress passed the Missing Children’s Assistance Act, which led to the creation of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

Former President Ronald Reagan opened the center in a White House ceremony in 1984. It soon began operating a 24-hour toll-free hot line on which callers could report information about missing boys and girls.